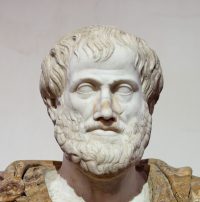

The Nicomachean Ethics holds a very special place in my heart. I have always been an avid reader and have had many ‘favorite books’ throughout my childhood, but this book is the first one that really resonated with me in a way that affected me to consciously alter the way I conceptualize the world and behave in it. I was introduced to it by Benjamin Morison as a first year undergraduate student at Princeton University in Fall 2014. While I personally disagree with or suspend judgment on many of the claims Aristotle makes, I find it an extremely valuable exercise for my own philosophical and personal development to study this book very closely.

In this page I aim to record my own preliminary translation of Nicomachean Ethics Book I to improve my understanding of the text. I will further update this page in the long-term as my understanding of Aristotle’s philosophy, his writing style, and Attic Greek improves. For now I aim to stay as close to the ~vibes~ of the original Greek as possible, as was the methodology at the Latin and Greek Institute at CUNY where I learned Greek from Hardy Hansen of the Hansen and Quinn textbook. Of course, I realize what you see below is not English… but neither is Greek ;).

Ethica Nicomachea Book I: the good as eudaimonia

Chapter 1:

Ἀρχαία Ἐλληνικά

[1094a] Πᾶσα τέχνη καὶ πᾶσα μέθοδος, ὁμοίως δὲ πρᾶξίς τε καὶ προαίρεσις, ἀγαθοῦ τινὸς ἐφίεσθαι δοκεῖ‧ διὸ καλῶς ἀπεφήναντο τἀγαθόν, οὗ πάντ’ ἐφίεται. διαφορὰ δέ τις φαίνεται τῶν τελῶν‧ τὰ μὲν γάρ εἰσιν ἐνέργειαι, τὰ δὲ παρ’ αὐτὰς ἔργα τινά. ὧν δ’ εἰσὶ τέλη τινὰ παρὰ τὰς πράξεις, ἐν τούτοις [5] βελτίω πέφυκε τῶν ἐνεργειῶν τὰ ἔργα. πολλῶν δὲ πράξεων οὐσῶν καὶ τεχνῶν καὶ ἐπιστημῶν πολλὰ γίνεται καὶ τὰ τέλη‧ ἰατρικῆς μὲν γὰρ ὑγίεια, ναυπηγικῆς δὲ πλοῖον, στρατηγικῆς δὲ νίκη, οἰκονομικῆς δὲ πλοῦτος. ὅσαι [10] δ’ εἰσὶ τῶν τοιούτων ὑπὸ μίαν τινὰ δύναμιν, καθάπερ ὑπὸ τὴν ἱππικὴν χαλινοποιικὴ καὶ ὅσαι ἄλλαι τῶν ἱππικῶν ὁργάνων εἰσίν, αὕτη δὲ καὶ πᾶσα πολεμικὴ πρᾶξις ὑπὸ τὴν στρατηγικήν, κατὰ τὸν αὐτὸν δὴ πρόπον ἄλλαι ὑφ’ ἑτέρας‧ ἐν ἁπάσαις δὲ τὰ τῶν ἀρχιτεκτονικῶν τέλη πάντων [15] ἐστὶν αἱρετώτερα τῶν ὑπ’ αὐτά‧ τούτων γὰρ χάριν κἀκεῖνα διώκεται. διαφέρει δ’ οὐδὲν τὰς ἐνεργείας αὐτὰς εἶναι τὰ τέλη τῶν πράξεων ἢ παρὰ ταύτας ἄλλο τι, καθάπερ ἐπὶ τῶν λεχθεισῶν ἐπιστημῶν.

Some sort of English [Note to self: task-smooth out.]

[1094a] Every craft and every inquiry, and similarly every action and choice, seems to aim at some good; this is why people declared that all things aim at ‘the good’. But some difference is apparent of the ends, because some ends are activities and others are some products produced by activities. Of the latter sort, 5 the products are by nature better than the actions. Because there are many actions, arts and sciences, there are many ends. Health is the end of medicine, a ship is the end of shipbuilding, victory is the end of generalship, and wealth is the end of household management. And many [likely, τέχναι:] arts are under some one power, just like 10 how bridle-making and all other arts producing tools for horsemanship is under horsemanship, and how horsemanship and every action for war is under generalship. In the same way, other [arts] are so under others; among all, the ends of the architectonic arts are more choiceworthy than all the ends under them, because, for the sake of these ends, 15 those are pursued. It makes no difference here whether the ends of actions are activities themselves or some other thing beside them, just like in the aforementioned sciences.

Chapter 2

[1094a18] Εἰ δή τι τέλος ἐστὶ τῶν πρακτῶν ὃ δι’ αὑτὸ βουλόμεθα, τἆλλα δὲ διὰ τοῦτο, καὶ μὴ [20] πάντα δι’ ἕτερον αἱρούμεθα (πρόεισι γὰρ οὕτω γ’ εἰς ἄπειρον, ὥστ’ εἶναι κενὴν καὶ ματαίαν τὴν ὄρεξιν), δῆλον ὡς τοῦτ’ ἂν εἴη τἀγαθὸν καὶ τὸ ἄριστον. ἆρ’ οὖν καὶ πρὸς τὸν βίον ἡ γνῶσις αὐτοῦ μεγάλην ἔχει ῥοπήν, καὶ καθάπερ τοξόται σκοπὸν ἔχοντες μᾶλλον ἂν τυγχάνοιμεν τοῦ δέοντος; εἰ δ’ [25] οὕτω, πειρατέον τύπῳ γε περιλαβεῖν αὐτὸ τί ποτ’ ἐστὶ καὶ τίνος τῶν ἐπιστημῶν ἢ δυνάμεων. δὀξειε δ’ ἂν τῆς κυριωτάτης καὶ μάλιστα ἀρχιτεκτονικῆς. τοιαύτη δ’ ἡ πολιτικὴ φαίνεται‧ τίνας γὰρ εἶναι χρεὼν τῶν ἐπιστημῶν ἐν ταῖς πόλεσι, [1094b] καὶ ποίας ἑκάστους μανθάνειν καὶ μέχρι τίνος, αὕτη διατάσσει‧ ὁρῶμεν δὲ καὶ τὰς ἐντιμοτάτας τῶν δυνάμεων ὑπὸ ταύτην οὔσας, οἷον στρατηγικὴν οἰκονομικὴν ῥητορικήν‧ χρωμένης δὲ ταύτης ταῖς λοιπαῖς [πρακτικαῖς] τῶν ἑπιστημῶν, [5] ἔτι δὲ νομοθετούσης τί δεῖ πράττειν καὶ τίνων ἀπέχεσθαι, τὸ ταύτης τέλος περιέχοι ἂν τὰ τῶν ἄλλων, ὥστε τοῦτ’ ἂν εἴη τἀνθρώπινον ἀγαθόν. εἰ γὰρ καὶ ταὐτόν ἐστιν ἑνὶ καὶ πόλει, μεῖζόν γε καὶ τελειότερον τὸ τῆς πόλεως φαίνεται καὶ λαβεῖν καὶ σῴζειν‧ ἀγαπητὸν μὲν γὰρ καὶ ἑνὶ [10] μόνῳ, κάλλιον δὲ καὶ θειότερον ἔθνει καὶ πόλεσιν. ἡ μὲν οὖν μέθοδος τούτων ἐφίεται, πολιτική τις οὖσα.

[1094a18] If actions have some [end] which we want on account of itself, but we want other things on account of this end, and [if] we don’t choose 20 everything on account of another (for then we’d have an infinite regress, and desire would be empty and vain), [then] it is clear that this end would be the best good. Therefore, knowledge of the good holds a great weight towards our life–and like archers who have a target–wouldn’t hitting the target be even more necessary? If this is right, 25 we must attempt at least in outline to comprehend what it is and of which science or power it is under. It would seem that the best good is of the most authoritative and the most architectonic (science or power). Politics appears to be of this sort, for it assigns which sciences are needed by the city [1094b] and what every man to what extent must learn; we see also that the most honored of the powers is under this science, e.g. generalship, household management, and rhetoric. This science (namely, politics), uses the rest of the sciences 5 and also legsilates what it is necessary to do and from what to abstain. The end of politics, then, would encompass the ends of the others, and would be the human good. For even if the good is the same for one man as it is for a city, to grasp and to save the good of the city at any rate appears to be a greater and more complete thing. For the good for one man is desirable even to one man alone, 10 but the good for a nation and a city is more noble and more divine. Thus, our inquiry aims at these things, being some political thing.

Chapter 3

[1094b11] Λέγοιτο δ’ ἂν ἱκανῶς, εἰ κατὰ τὴν ὑποκειμένην ὕλην διασαφηθείη‧ τὸ γὰρ ἀκριβὲς οὐχ ὁμοίως ἐν ἅπασι τοῖς λόγοις ἐπιζητητέον, ὥςπερ οὐδ’ ἐν τοῖς δημιουργουμένοις. τὰ δὲ καλὰ καὶ τὰ δίκαια, [15] περὶ ὧν ἡ πολιτικὴ σκοπεῖται, πολλὴν ἔχει διαφορὰν καὶ πλάνην, ὥστε δοκεῖν ωόμῳ μόνον εἶναι, φύσει δὲ μή. τοιαύτην δέ τινα πλάνην ἔχει καὶ τἀγαθὰ διὰ τὸ πολλοῖς συμβαίνειν βλάβας ἀπ’ αὐτῶν‧ ἤδη γάρ τινες ἀπώλοντο διὰ πλοῦτον, ἕτεροι δὲ δι’ ἀνδρείαν. ἀγαπητὸν οὖν περὶ τοιούτων [20] καὶ ἐκ τοιούτων λέγοντας παχυλῶς καὶ τύπῳ τἀληθὲς ἐνδείκνυσθαι, καὶ περὶ τῶν ὡς ἐπὶ τὸ πολὺ καὶ ἐκ τοιούτων λέγοντας τοιαῦτα καὶ συμπεραίνεσθαι. τὸν αὐτὸν δὴ τρόπον καὶ ἀποδέχεσθαι χρεὼν ἕκαστα τῶν λεγομένων‧ πεπαιδευμένου γάρ ἐστιν ἐπὶ τοσοῦτον τἀκριβὲς ἐπιζητεῖν καθ’ ἕκαστον [25] γένος, ἐφ’ ὅσον ἡ τοῦ πράγματος φύσις ἐπιδέχεται‧ παραπλήσιον γὰρ φαίνεται μαθηματικοῦ τε πιθανολογοῦντος ἀποδέχεσθαι καὶ ῥητορικὸν ἀποδείξεις ἀπαιτεῖν. ἕκαστος δὲ κρίνει καλῶς ἃ γινώσκει, καὶ τούτων ἐστὶν ἀγαθὸς κριτής. καθ’ [1095a] ἕκαστον μὲν ἄρα ὁ πεπαιδυμένος, ἁπλῶς δ’ ὁ περὶ πᾶν πεπαιδευμένος. διὸ τῆς πολιτικῆς οὐκ ἔστιν οἰκεῖος ἀκροατὴς ὁ νέος‧ ἄπειρος γὰρ τῶν κατὰ τὸν βίον πράξεων, οἱ λόγοι δ’ ἐκ τούτων καὶ περὶ τούτων‧ ἔτι δὲ τοῖς πάθεσιν ἀκολουθητικὸς ὢν [5] ματαίως ἀκούσεται καὶ ἀνωφελῶς, ἐπειδὴ τὸ τέλος ἐστὶν οὐ γνῶσις ἀλλὰ πρᾶξις. διαφέρει δ’ οὐδὲν νέος τὴν ἡλικίαν ἢ τὸ ἦθος νεαρός‧ οὐ γὰρ παρὰ τὸν χρόνον ἡ ἔλλειψις, ἀλλὰ διὰ τὸ κατὰ πάθος ζῆν καὶ διώκειν ἕκαστα. τοῖς γὰρ τοιούτοις ἀνόνητος ἡ γνῶσις γίνεται, καθάπερ τοῖς ἀκρατέσιν‧ [10] τοῖς δὲ κατὰ λόγον τὰς ὀρέξεις ποιουμένοις καὶ πράττουσι πολυωφελὲς ἂν εἴη τὸ περὶ τούτων εἰδέναι. καὶ περὶ μὲν ἀκροατοῦ καὶ πῶς ἀποδεκτέον, καὶ τί προτιθέμεθα, πεφροιμιάσθω ταῦτα.

[1094b11] It would be sufficiently said, if it is made clear according to the underlying subject matter, for it is not necessary to seek out precision to the same degree in all arguments, just as it is not in the crafts. The beautiful/noble and just things 15–which are the things with which politics is concerned–greatly differ and ‘wander’ (πλάνη). This makes it seem as though they are what they are by custom only and not by nature. Even good things seem to ‘wander’ in the same way when we consider the accounts of harms befalling many people because of them. For example, some have died because of wealth, others because of courage. It is thus desirable when speaking about these things and from these sorts of premises: to point out coarsely and in outline what is true; 20 and when speaking about things which hold for the most part and from premises which hold for the most part: to conclude [only] things as such. It is also necessary to in the same way demonstrate each thing we discuss; for the educated person seeks out precision according to each kind, until so much, up to as much, admitted by the nature of the subject, 25 for it appears similarly [absurd] to accept a methematician arguing from probability as to ask a rhetorician for a proof. Each person judges beautifully/nobly the things which he knows, of these things they are a good judge. [1095a] Thus, the good judge of one thing is the person who has been educated in that thing, and the unqualifiedly good judge is the person who has been educated in all things. Thus, the young person is not a suitable student of politics; for they are inexperienced in the actions concerning their lives, and the accounts/arguments (λογοι) about [actions in life] are [built] from [actions in life]. Being disposed to follow his emotions, 5 the person will vainly and unprofitably listen, because the end is not knowledge, but action. It makes no difference, however, whether the person is young with respect to age or with respect to character, for the [relevant] deficiency is not in time, but in life with experience and in pursuing each [action]. For, for the people deficient in this way knowledge is uselss, just as for the people lacking self-control. For the people who produce their desires and actions according to reason, 10 knowledge about these things (politics) would be advantageous.

We have, then, prefaced the student of our inquiry, the way in which there must be a demonstration and what we propose to do.

Chapter 4

[1095a14] Λέγωμεν δ’ ἀναλαβόντες, ἐπειδὴ πᾶσα γνῶσις καὶ προαίρεσις [15] ἀγαθοῦ τινὸς ὀρέγεται, τί ἐστὶν οὗ λέγομεν τὴν πολιτικὴν ἐφίεσθαι καὶ τί τὸ πάντων ἀκρότατον τῶν πρακτῶν ἀγαθῶν. ὀνοματι μὲν οὖν σχεδὸν ὑπὸ τῶν πλείστων ὁμολογεῖται‧ τὴν γὰρ εὐδαιμονίαν καὶ οἱ πολλοὶ καὶ οἱ χαρίεντες λέγουσιν, τὸ δ’ εὖ ζῆν καὶ τὸ εὖ πράττειν ταὐτὸν ὑπολαμβάνουσι [20] τῷ εὐδαιμονεῖν‧ περὶ δὲ τῆς εὐδαιμονίας, τί ἐστιν, ἀμφισβητοῦσι καὶ οὐχ ὁμοίως οἱ πολλοὶ τοῖς σοφοῖς ἀποδιδόασιν. οἳ μὲν γὰρ τῶν ἐναργῶν τι καὶ φανερῶν, οἷον ἡδονὴν ἢ πλοῦτον ἢ τιμήν, ἄλλοι δ’ ἄλλο–πολλάκις δὲ καὶ ὁ αὐτὸς ἕτερον‧ νοσήσας μὲν γὰρ ὑγίειαν, πενόμενος δὲ [25] πλοῦτον‧ συνειδότες δ’ ἑαυτοῖς ἄγνοιαν τοὺς μέγα τι καὶ ὑπὲρ αὐτοὺς λέγοντας θαυμάζουσιν. ἔνιοι δ’ ᾤοντο παρὰ τὰ πολλὰ ταῦτα ἀγαθὰ ἄλλο τι καθ’ αὑτὸ εἶναι, ὃ καὶ τούτοις πᾶσιν αἴτιόν ἐστι τοῦ εἶναι ἀγαθά. ἁπάσας μὲν οὖν ἐξετάζειν τὰς δόξας ματαιότερον ἴσως ἐστίν, ἱκανὸν δὲ τὰς μάλιστα [30] ἐπιπολαζούσας ἢ δοκούσας ἔχειν τινὰ λόγον. μὴ λανθανέτω δ’ ἡμᾶς ὅτι διαφέρουσιν οἱ ἀπὸ τῶν ἀρχῶν λόγοι καὶ οἱ ἐπὶ τὰς ἀρχάς. εὖ γὰρ καὶ ὁ Πλάτων ἠπόρει τοῦτο καὶ ἐζήτει, πότερον ἀπὸ τῶν ἀρχῶν ἢ ἐπὶ τὰς ἀρχάς ἐστιν ἡ ὁδός, ὥσπερ [1095b] εν τῷ σταδίῳ ἀπὸ τῶν ἀθλοθετῶν ἐπὶ τὸ πέρας ἢ ἀνάπαλιν. ἀρκτέον μὲν γὰρ ἀπὸ τῶν γνωρίμων, ταῦτα δὲ διττῶς‧ τὰ μὲν γὰρ ἡμῖν τὰ δ’ ἁπλῶς. ἴσως οὖν ἡμῖν γε ἀρκτέον ἀπὸ τῶν ἡμῖν γνωρίμων. διὸ δεῖ τοῖς ἔθεσιν ἦχθαι καλῶς τὸν [5] περὶ καλῶν καὶ δικαίων καὶ ὅλως τῶν πολιτικῶν ἀκουσόμενον ἱκανῶς. ἀρχὴ γὰρ τὸ ὅτι, καὶ εἰ τοῦτο φαίνοιτο ἀρκούντως, οὐδὲν προσδεήσει τοῦ διότι‧ ὁ δὲ τοιοῦτος ἔχει ἢ λάβοι ἂν ἀρχὰς ῥᾳδιως. ᾧ δὲ μηδέτερον ὑπάρχει τούτων ἁκουσάτω τῶν Ἡσιόδου‧

[10] οὗτος μὲν πανάριστος ὃς αὐτὸς πάντα νοήσῃ,

ἐσθλὸς δ’ αὖ κἀκεῖνος ὃς εὖ εἰπόντι πίθηται.

ὃς δέ κε μήτ’ αὐτὸς νοέῃ μήτ’ ἄλλου ἀκούων

ἐν θημῷ βάλληται, ὃ δ’ αὖτ’ ἀχρήιος ἀνήρ.

[1095a14] Let us then, take this up: given that every knowledge and choice aims at some good, what is the good at which politics aims, 15 and what is the best of all practical* goods? In name almost everyone agrees; for both the masses and the sophisticated say that it is εὐδαιμονία (happiness/prospering) and suppose that living well and faring well are the same 20 as εὐδαιμονία. But about what εὐδαιμονία is they dispute, and the masses disagree with the wise. Some people define it as one of the vivid and evident things, e.g. pleasure, wealth, or honor. Others define it as another, and often the same person defines it as another. For when one is ill, one defines it as health; when one is poor, one defines it 25 as wealth; knowing their own ignorance, they are in awe of those who say big things that are beyond them. Some people [the Platonists], however, have thought that beyond all these many good things, there is something else that is good [the Form of the Good] in virtue of itself and which is the cause for the existence of all good things. To investigate all the available opinions is perhaps rather vain; it is sufficient to investigate 30 the most prevalent or creditable opinions. And, let it not escape our notice that the accounts from the ἀρχῶν (principles) and the accounts for the ἀρχάς differ. Plato problematized and sought this: whether the way is from the principles or for the principles, just as [1095b] in the race-course, [the way is] from the judges to the end or in reverse. There must be a rule to begin from what is familiar, but there is an ambiguity about this, for [what is familiar] could either be familiar to us or be so simpliciter. Therefore, perhaps there must be a rule for us at any rate to begin from what is familiar to us. This is why it is necessary for the one who intends to properly learn 5 about noble and just things and about the whole of politics to have been brought up with noble habits. For an ἀρχή is that which [even if the why was adequately apparent] we do not need the ‘why’; the person of such a sort [brought up with noble habits] has or would easily take up the ἀρχαί. For those whom this is not true, they should listen to Hesiod:

10 The one who knows all things is best of all,

The one who obeys those who speak well is good.

The one who neither knows nor listens to another

Is thrown in his heart, and they themselves are useless.

Chapter 5

[1095b14] Ἡμεῖς δὲ λέγωμεν ὅθεν παρεξέβημεν. τὸ γὰρ ἀγαθὸν [15] καὶ τὴν εὐδαιμονίαν οὐκ ἀλόγως ἐοίκασιν ἐκ τῶν βίων ὑπολαμβάνειν οἱ μὲν πολλοὶ καὶ φορτικώτατοι τὴν ἡδονήν‧ διὸ καὶ τὸν βίον ἀγαπῶσι τὸν ἀπολαυστικόν. τρεῖς γάρ εἰσι μάλιστα οἱ προύχοντες, ὅ τε νῦν εἰρημένος καὶ ὁ πολιτικὸς καὶ τρίτος ὁ θεωρητικός. οἱ μὲν οὖν πολλοὶ παντελῶς ἀνδραποδώδεις [20] φαίνονται βοσκημάτων βίον προαιρούμενοι, τυγχάνουσι δὲ λόγου διὰ τὸ πολλοὺς τῶν ἐν ταῖς ἐξουσίαις ὁμοιοπαθεῖν Σαρδαναπάλλῳ. οἱ δὲ χαρίεντες καὶ πρακτικοὶ τιμήν‧ τοῦ γὰρ πολιτικοῦ βίου σχεδὸν τοῦτο τέλος. φαίνεται δ’ ἐπιπολαιότερον εἶναι τοῦ ζητουμένου‧ δοκεῖ γὰρ ἐν [25] τοῖς τιμῶσι μᾶλλον εἶναι ἢ ἐν τῷ τιμωμένῳ, τἀγαθὸν δὲ οἰκεῖόν τι καὶ δυσαφαίρετον εἶναι μαντευόμεθα. ἔτι δ’ ἐοίκασι τὴν τιμὴν διώκειν ἵνα πιστεύσωσιν ἑαυτοὺς ἀγαθοὺς εἶναι‧ ζητοῦσι γοῦν ὑπὸ τῶν φρονίμων τιμᾶσθαι, καὶ παρ’ οἷς γινώσκονται, καὶ ἐπ’ ἀρετῇ‧ δῆλον οὖν ὅτι κατά γε [30] τούτους ἡ ἀρετὴ κρείττων. τάχα δὲ καὶ μᾶλλον ἄν τις τέλος τοῦ πολιτικοῦ βίου ταύτην ὑπολάβοι. φαίνεται δὲ ἀτελεστέρα καὶ αὕτη‧ δοκεῖ γὰρ ἐνδέχεσθαι καὶ καθεύδειν ἔχοντα τὴν ἀρετὴν ἢ ἀπρακτεῖν διὰ βίου, καὶ πρὸς τούτοις [1096a] κακοπαθεῖν καὶ ἀτυχεῖν τὰ μέγιστα‧ τὸν δ’ οὕτω ζῶντα οὐδεὶς ἂν εὐδαιμονίσειεν, εἰ μὴ θέσιν διαφυλάττων. καὶ περὶ μὲν τούτων ἅλις‧ ἱκανῶς γὰρ καὶ ἐν τοῖς ἐγκυκλίοις εἴρηται περὶ αὐτῶν. τρίτος δ’ ἐστὶν ὁ θεωρητικός, ὑπὲρ οὖ “[5] τὴν ἐπίσκεψιν ἐν τοῖς ἑπομένοις ποιησόμεθα. ὁ δὲ χρηματιστὴς βίαιός τις ἐστίν, καὶ ὁ πλοῦτος δῆλον ὅτι οὐ τὸ ζητούμενον ἀγαθόν‧ χρήσιμον γὰρ καὶ ἄλλου χάριν. διὸ μᾶλλον τὰ πρότερον λεχθέντα τέλη τις ἂν ὑπολάβοι‧ δι’ αὑτα γὰρ ἀγαπᾶται. φαίνεται δ’ οὐδ’ ἐκεῖνα‧ καίτοι πολλοὶ λόγοι πρὸς αὐτὰ καταβέβληνται. ταῦτα μὲν οὖν ἀφείσθω.

[1095b14] Let us speak from where we digressed. For 15 the masses and the most vulgar are not unreasonably likely to suppose from their lives that the good and εὐδαιμονία is pleasure; this is why they are content with the life of enjoyment. Three lives are especially outstanding [in being considered the best]; the life of pleasure, the political life, and third, the contemplative life. The masses appear to be completely slavish, 20 choosing a life of cattle, yet they have an account like many in positions of power have experienced, e.g. Sardanapallos. The sophisticaed and the pragmatic choose honor; for this is almost the end (τελος) of the political life. 25 But honor appears to be more superficial than what we’re looking for, since honor seems dependent more on the people honoring than on the ones being honored, and we would think that the good is something suitable to and hard to detach from those who have achieved it. Further, those who seek honor seem to pursue it so that they may trust themselves to be good. For example, they seek being honored by the φρονίμων among those who recognize them and on the condition of virtue. Therefore, it is clear that virtue is superior to honor. 30 But then perhaps someone would suppose that the end of the political life is virtue. This, however, appears more incomplete, since it seems possible that the person possessing virtue can sleep or be idle, and further [1096a] to suffer ills and be more greatly unfortunate; and the one whose life is so would not be considered eudaimonic, except to play devil’s advocate. Enough about this; these matters are sufficiently discussed among the exoteric works. The third life is the contemplative life, on behalf of which 5 we will inquire. The money-maker is constrained and it is clear that wealth is not the good that is being sought, since it is good, useful for the sake of something else. Thus, any of the previous ones are better candidates. Yet none of those appear to work as the best good; indeed many arguments have been thrown against them, thus let’s leave them be.

Chapter 6

[1096a11] Τὸ δὲ καθόλου βέλτιον ἴσως ἐπισκέψασθαι καὶ διαπορῆσαι πῶς λέγεται, καίπερ προσάντους τῆς τοιαύτης ζητήσεως γινομένης διὰ τὸ φίλους ἄνδρας εἰσαγαγεῖν τὰ εἴδη. δόξειε δ’ ἂν ἴσως βέλτιον εἶναι καὶ δεῖν ἐπὶ σωτηρίᾳ γε τῆς [15] ἀληθείας καὶ τὰ οἰκεῖα ἀναιρεῖν, ἄλλως τε καὶ φιλοσόφους ὄντας‧ ἀμφοῖν γὰρ ὄντοιν φίλοιν ὅσιον προτιμᾶν τὴν ἀλήθειαν. οἱ δὴ κομίσαντες τὴν δόξαν ταύτην οὐκ ἐποίουν ἰδέας ἐν οἷς τὸ πρότερον καὶ ὕστερον ἔλεγον, διόπερ οὐδὲ τῶν ἀριθμῶν ἰδέαν κατεσκεύαζον‧ τὸ δ’ ἀγαθὸν λέγεται καὶ ἐν [20] τῷ τί ἐστι καὶ ἐν τῷ ποιῷ καὶ ἐν τῷ προός τι, τὸ δὲ καθ’ αὑτὸ καὶ ἡ οὐσία πρότερον τῇ φύσει τοῦ πρός τι (παραφυάδι γὰρ τοῦτ’ ἔοικε καὶ συμβεβηκότι τοῦ ὄντος)‧ ὥστ’ οὐκ ἂν εἴη κοινή τις ἐπὶ τούτοις ἰδέα. ἔτι δ’ ἐπεὶ τἀγαθὸν ἰσαχῶς λέγεται τῷ ὄντι (καὶ γὰρ ἐν τῷ τί λέγεται, οἷον ὁ θεὸς καὶ [25] ὁ νοῦς, καὶ ἐν τῷ ποιῷ αἱ ἀρεταί, καὶ ἐν τῷ ποσῷ τὸ μέτριον, καὶ ἐν τῷ πρός τι τὸ χρήσιμον, καὶ ἐν χρόνῳ καιρός, καὶ ἐν τόπῳ δίαιτα καὶ ἕτερα τοιαῦτα), δῆλον ὡς οὐκ ἂν εἴη κοινόν τι καθόλου καὶ ἕν‧ οὐ γὰρ ἂν ἐλέγετ’ ἐν πάσαις ταῖς κατηγορίαις, ἀλλ’ ἐν μιᾷ μόνῃ. ἔτι δ’ ἐπεὶ τῶν [30] κατὰ μίαν ἰδέαν μία καὶ ἐπιστήμη, καὶ τῶν ἀγαθῶν ἁπάντων ἦν ἂν μία τις ἐπιστήμη‧ νῦν δ’ εἰσὶ πολλαὶ καὶ τῶν ὑπὸ μίαν κατηγορίαν, οἷον καιροῦ, ἐν πολέμῳ μὲν γὰρ στρατηγικὴ ἐν νόσῳ δ’ ἰατρική, καὶ τοῦ μετρίου ἐν τροφῇ μὲν ἰατρικὴ ἐν πόνοις δὲ γυμναστική. ἀπορήσειε δ’ ἄν τις τί [35] ποτε καὶ βούλονται λέγειν αὐτοέκαστον, εἴπερ ἔν τε αὐτοανθρώπῳ [1096b] καὶ ἐν ἀνθρώπῳ εἶς καὶ ὁ αὐτὸς λόγος ἐστὶν ὁ τοῦ ἀνθρώτου. ᾗ γὰρ ἄνθρωπος, οὐδὲν διοίσουσιν‧ εἰ δ’ οὕτως, οὐδ’ ᾗ ἀγαθόν. ἀλλὰ μὴν οὐδὲ τῷ ἀίδιον εἶναι μᾶλλον ἀγαθὸν ἔσται, εἴπερ μηδὲ λευκότερον τὸ πολυχρόνιον τοῦ [5] ἐφημέρου. πιθανώτερον δ’ ἐοίκασιν οἱ Πυθαγόρειοι λέγειν περὶ αὐτοῦ, τιθέντες ἐν τῇ τῶν ἀγαθῶν συστοιχίᾳ τὸ ἕν‧ οἷς δὴ καὶ Σπεύσιππος ἐπακολουθῆσαι δοκεῖ. ἀλλὰ περὶ μὲν τούτων ἄλλος ἔστω λέγος‧

[1096a11] Presumably it is better to examine the universal good, [i.e. Plato’s Form of the Good] and raise problems about the way it is spoken of, though this sort of inquiry is unpleasant because those who introduced the Forms [i.e. Plato &Co.] are our friends. It is presumably still better, even necessary, in the preservation of truth 15 to demolish even what is close to us [i.e. our friends’ opinions], especially if one is a philosopher. For though we love both [our friends and the truth], honoring the truth comes first. In fact, those with this belief were not postulating forms for things spoken about with a ‘prior’ and ‘posterior’; on their account they were not maintaining a Form of the numbers. Further, the good is spoken of as 20 what-it-is [substance] (see Cat. & Top.), in quality, and as relative, also as existing on its own; and the substance is prior by nature to the relative (for this is like an offshoot and accident of being) so there is no common Form. And besides, since the good is spoken of in the same number of ways as substance (for it is spoken of also in substance, for example as god and 25 mind (νοῦς), in quality as the virtues, in quantitiy as the measure, in relative as the useful, in time as the opportune moment, in place as the [right] mode of life and others in such a way), it is clear that there is not a common, universal and singular thing, for [if there were] it would not be spoken of in all the categories, but in only one. And besides, when 30 there are things according to one Form, then there would be a science of them; thus, if there were a Form of all good things, there would be some single science of all goods. But now there are many sciences under one category. For example, under opportune moment: in war, strategy; in sickness, medicine. Under the measure: in food, medicine; in exercise, gymnastics. Someone may be at a loss 35 about whatever they [the Platonists] meant to say about a Form, if indeed [under their conception] in the Form of man [1096b] and in a man there is the same account of ‘man’. For qua man, they do not differ. And if so, then nothing will differ for ‘good’. And surely something ‘good’ is not any more good by being eternal, if indeed a white thing is not whiter by being long-lasting than 5 short-lived. The Pythagoreans had something more persuasive to say concerning this: they placed the ‘One’ in the coordinate series of the goods, and even Speusippus seems to have followed them. But concerning these matters, let us leave it for another discussion.

τοῖς δὲ λεχθεῖσιν ἀμφισβήτησίς τις ὑποφαίνεται διὰ τὸ μὴν περὶ παντὸς ἀγαθοῦ τοὺς λόγους [10] εἰρῆσθαι, λέγεσθαι δὲ καθ’ ἓν εἶδος τὰ καθ’ αὑτὰ διωκόμενα καὶ ἀγαπώμενα, τὰ δὲ ποιητικὰ τούτων ἢ φυλακτικά πως ἢ τῶν ἐναντίων κωλυτικὰ διὰ ταῦτα λέγεσθαι καὶ τρόπον ἄλλον. δῆλον οὖν ὅτι διττῶς λέγοιτ’ ἂν τἀγαθά, καὶ τὰ μὲν καθ’ αὑτά, θάτερα δὲ διὰ ταῦτα. χωρίσαντες [15] οὖν ἀπὸ τῶν ὠφελίμων τὰ καθ’ αὑτὰ σκεψώμεθα εἰ λέγεται κατὰ μίαν ἰδέαν. καθ’ αὑτὰ δὲ ποῖα θείη τις ἄν; ἢ ὅσα καὶ μονούμενα διώκεται, οἷον τὸ φρονεῖν καὶ ὁρᾶν καὶ ἡδοναί τινες καὶ τιμαί; ταῦτα γὰρ εἰ καὶ δι’ ἄλλο τι διώκομεν, ὅμως τῶν καθ’ αὑτὰ ἀγαθῶν θείη τις ἄν. ἢ οὐδ’ [20] ἄλλο οὐδὲν πλὴν τῆς ἰδέας; ὥστε μάταιον ἔσται τὸ εἶδος. εἰ δὲ καὶ ταῦτ’ ἐστὶ τῶν καθ’ αὑτά τὸν τἀγαθοῦ λόγον ἐν ἅπασιν αὐτοῖς τὸν αὐτὸν ἐμφαίνεσθαι δεήσει, καθάπερ ἐν χιόνι καὶ ψιμυθίῳ τὸν τῆς λευκότητος. τιμῆς δὲ καὶ φρονήσεως καὶ ἡδονῆς ἕτεροι καὶ διαφέροντες οἱ λόγοι ταύτῃ [25] ᾖ ἀγαθά. οὐκ ἔστιν ἄρα τὸ ἀγαθὸν κοινόν τι κατὰ μίαν ἰδέαν. ἀλλὰ πῶς δὴ λέγεται; οὐ γὰρ ἔοικε τοῖς γε ἀπὸ τύχης ὁμωνύμοις. ἀλλ’ ἆρά γε τῷ ἀφ’ ἑνὸς εἶναι ἢ πρὸς ἓν ἅπαντα συντελεῖν, ἢ μᾶλλον κατ’ ἀναλογίαν; ὡς γὰρ ἐν σώματι ὄψις, ἐν ψυχῇ νους, καὶ ἄλλο δὴ ἐν ἄλλῳ. [30] ἀλλ’ ἴσως ταῦτα μὲν ἀφετέον τὸ νῦν‧ ἐξακριβοῦν γὰρ ὑπὲρ αὐτῶν ἄλλης ἂν εἴη φιλοσοφίας οἰκειότερον. ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ περὶ τῆς ἰδέας‧ εἰ γὰρ καὶ ἔστιν ἕν τι τὸ κοινῇ κατηγορούμενον ἀγαθὸν ἢ χωριστὸν αὐτό τι καθ’ αὑτό, δῆλον ὡς οὐκ ἂν εἴη πρακτὸν οὐδὲ κτητὸν ἀνθρώπῳ‧ νῦν δὲ τοιοῦτόν τι [35] ζητεῖται.

With respect to what has been said, some dispute emerges through our question concerning the accounts of the whole good. 10 whether the goods being pursued and loved should be spoken of as one form or whether they should be spoken of in terms of how they preserve the things they produce or of their opposites how they prevent these things by how they are said or in another another way (?). Therefore it is clear that the good is spoken of in two ways; some on account of themselves, others through these. Divided, 15 then, from the useful goods, let us see whether the ones good on account of themselves is spoken of according to one form. Of what sort are [the goods] good on account of themselves? Or how much is it pursued even on its own? For example, τὸ φρονεῖν (varying translations, prudence, practical wisdom, etc.), sight, some pleasures and honor. For even if we pursue these things for the sake of something else, one would nevertheless place them among the goods that are good on account of themselves. Or would nothing 20 except the Form [be placed among the goods according to themselves], so that the Form will be empty? But if these examples (see: phronesis, sight, etc. above) are also goods on account of themselves, it would be necessary that the same account of the good is shown in all of them in the same way, just as whiteness is shown in snow and white lead in the same way. Yet the accounts differentiating honor, φρονήσεως and pleasures are different 25 with respect to these goods. So the good is not something common to one Form. But how is it in fact spoken of? For it seems not from chance homonyms. Is it spoken of as coming from one thing or all towards one thing bringing to an end or more as according to an analogy? For just as in body is sight, also in soul is mind, etc. 30 But perhaps we should let these things be for now, because it would be more appropriate to be spelled out over another field of philosophy. And similarly, the Form [would also be more appropriate to be spelled out elsewhere]. For, if the good predicated in common [among all good things] is some one thing or something separable on its own, then it is clear how [the good] is nothing that can be practically acquired by a person; but now something of this sort [something that can be practically acquired] 35 is what we are looking for.

τάχα δέ τῳ δόξειεν ἂν βέλτιον εἶναι γνωρίζειν [1097a] αὐτὸ πρὸς τὰ κτητὰ καὶ πρακτὰ τῶν ἀγαθῶν‧ οἷον γὰρ παράδειγμα τοῦτ’ ἔχοντες μᾶλλον εἰσόμεθα καὶ τὰ ἡμῖν ἀγαθά, κἂν εἰδῶμεν, ἐπιτευξόμεθα αὐτῶν. πιθανότητα μὲν οὖν τινα ἔχει ὁ λόγος, ἔοικε δὲ ταῖς ἐπιστήμαις διαφωνεῖν‧ [5] πᾶσαι γὰρ ἀγαθοῦ τινὸς ἐφιέμεναι καὶ τὸ ἐνδεὲς ἐπιζητοῦσαι παραλείπουσι τὴν γνῶσιν αὐτοῦ. καίτοι βοήθημα τηλικοῦτον τοὺς τεχνίτας ἅπαντας ἀγνοεῖν καὶ μηδ’ ἐπιζητεῖν οὐκ εὔλογον. ἄπορον δὲ καὶ τί ὠφεληθήσεται ὑφάντης ἢ τέκτων πρὸς τὴν αὑτοῦ τέχνην εἰδὼς τὸ αὐτὸ τοῦτο ἀγαθόν, [10] ἢ πῶς ἰατρικώτερος ἢ στρατηγικώτερος ἔσται ὁ τὴν ἰδέαν αὐτὴν τεθεαμένος. φαίνεται μὲν γὰρ οὐδὲ τὴν ὑγίειαν οὕτως ἐπισκοπεῖν ὁ ἰατρός, ἀλλὰ τὴν ἀνθρώπου, μᾶλλον δ’ ἴσως τὴν τοῦδε‧ καθ’ ἕκαστον γὰρ ἰατρεύει. καὶ περὶ μὲν τούτων ἐπὶ τοσοῦτον εἰρήσθω.

But perhaps one would think it better to know (γνωρίζω) [1097a] it [the good? the Form?] with reference to the goods that may be gotten and doable, becuase for example, if it has this pattern, then we will also know (οἶδα) [middle] more the things that are good for us, and we would see that we will hit the mark on these. The argument, then, has some persuasiveness, and it seems to be different from the sciences. 5 For all, though longing for some good, also seeks a deficient thing and leaves out to the side, the knowledge (γνῶσις) of it [the good]. And yet, a resource of such a magnitive would not make sense for all the artisans to not know nor seek. And a puzzle also is what a weaver or carpenter will gain with respect to their craft in knowing this good itself, 10 or how a medical or strategic man will be helped beholding the Form itself. For the doctor appears to not look upon health in this way, but [upon] health of humans, and perhaps the health of [humans] is greater, for [it is] according to [this that] he cures. And concerning these [matters], let us have spoken for so much.

Chapter 7:

[1097a15] Πάλιν δ’ ἐπανέλθωμεν ἐπὶ τὸ ζητούμενον ἀγαθόν, τί ποτ’ ἂν εἴη. φαίνεται μὲν γὰρ ἄλλο ἐν ἄλλῃ πράξει καὶ τέχνῃ‧ ἄλλο γὰρ ἐν ἰατρικῇ καὶ στρατηγικῇ καὶ ταῖς λοιπαῖς ὁμοίως. τί οὖν ἑκάστης τἀγαθόν; ἢ οὗ χάριν τὰ λοιπὰ πράττεται; τοῦτο δ’ ἐν ἰατρικῇ μὲν ὑγίεια, ἐν στρατηγικῇ [20] δὲ νίκη, ἐν οἰκοδομικῇ δ’ οἰκία, ἐν ἄλλῳ δ’ ἄλλο, ἐν ἁπάσῃ δὲ πράξει καὶ προαιρέσει τὸ τέλος‧ τούτου γὰρ ἕνεκα τὰ λοιπὰ πράττουσι πάντες. ὥστ’ εἴ τι τῶν πρακτῶν ἁπάντων ἐστὶ τέλος, τοῦτ’ ἂν εἴη τὸ πρακτὸν ἀγαθόν, εἰ δὲ πλείω, ταῦτα. μεταβαίνων δὲ ὁ λόγος εἰς ταὐτὸν ἀφῖκται‧ τοῦτο [25] δ’ ἔτι μᾶλλον διασαφῆσαι πειρατέον. ἐπεὶ δὲ πλείω φαίνεται τὰ τέλη, τούτων δ’ αἱρούμεθά τινα δι’ ἕτερον, οἷον πλοῦτον αὐλοὺς καὶ ὅλως τὰ ὄργανα, δῆλον ὡς οὐκ ἔστι πάντα τέλεια‧ τὸ δ’ ἄριστον τέλειόν τι φαίνεται. ὥστ’ εἰ μέν ἐστιν ἕν τι μόνον τέλειον, τοῦτ’ ἂν εἴη τὸ ζητούμενον, [30] εἰ δὲ πλείω, τὸ τελειότατον τούτων. τελειότερον δὲ λέγομεν τὸ καθ’ αὑτὸ διωκτὸν τοῦ δι’ ἕτερον καὶ τὸ μηδέποτε δι’ ἄλλο αἱρετὸν τῶν <καὶ> καθ’ αὑτὰ καὶ δι’ αὐτὸ αἱρετῶν, καὶ ἁπλῶς δὲ τέλειον τὸ καθ’ αὑτὸ αἱρετὸν ἀεὶ καὶ μηδέποτε δι’ ἄλλο. τοιοῦτον δ’ ἡ εὐδαιμονία μάλιστ’ εἶναι δοκεῖ‧

[1097a15] Let us turn back to searching the good, whatever it might be. For there appears to be another [good] in another action or another craft; for there is another good in medicine, in strategy, and similarly in the rest. What then is the good of each? Or for the sake of what is the rest done? In medicine, this is health, in strategy 20 victory, in architecture a house, in another another, and in quite all action and decision this [the good] is the end, for it is for the sake of the end that all do the rest. Thus, if there is some end of quite all actions, then this end would be the active good, if there are many more, then those ends would be. The argument passing over from one place to another has come to the same. Yet 25 we must try to make this more clear. And since there appears to be many more ends, of these some we choose through another. For example, we choose wealth, auloses, and generally the instruments [through another end]. It is clear that all these are not complete. Something appears to be the most complete end. Therefore, if there is some one and only complete [end], then this would be that being sought; 30 if there are many, the most complete of these. We say that the [end] pursued on account of itself is more complete than the [end] pursued through another and that the [end] never chosen through another is more complete than the [ends] chosen on account of that and through that, and that the end complete without qualification is the [end] chosen on account of itself and always not ever through another. It seems to be that eudaimonia is most of all this sort of thing.

[1097b] τιμὴν δὲ καὶ ἡδονὴν καὶ νοῦν καὶ πᾶσαν ἀρετὴν αἱρούμεθα μὲν καὶ δι’ αὐτά (μηθενὸς γὰρ ἀποβαίνοντος ἑλοίμεθ’ ἂν ἑκαστον αὐτῶν), αἱρούμεθα δὲ καὶ τῆς εὐδαιμονίας χάριν, [5] διὰ τούτων ὑπολαμβάνοντες εὐδαιμονήσειν. τὴν δ’ εὐδαιμονίαν οὐδεὶς αἱρεῖται τούτων χάριν, οὐδ’ ὅλως δι’ ἄλλο. φαίνεται δὲ καὶ ἐκ τῆς αὐταρκείας τὸ αὐτὸ συμβαίνειν‧ τὸ γὰρ τέλειον ἀγαθὸν αὔταρκες εἶναι δοκεῖ. τὸ δ’ αὔταρκες λέγομεν οὐκ αὐτῷ μόνῳ, τῷ ζῶντι βίον μονώτην, ἀλλὰ καὶ γονεῦσι [10] καὶ τέκνοις καὶ γυναικὶ καὶ ὅλως τοῖς φίλοις καὶ πολίταις, ἐπειδὴ φύσει πολιτικὸν ὁ ἄνθρωπος. τούτων δὲ ληπτέος ὅρος τις‧ ἐπεκτείνοντι γὰρ ἐπὶ τοὺς γονεῖς καὶ τοὺς ἀπογόνους καὶ τῶν φίλων τοὺς φίλους εἰς ἄπειρον πρόεισιν. ἀλλὰ τοῦτο μὲν εἰσαῦθις ἐπισκεπτέον‧ τὸ δ’ αὔταρκες τίθεμεν ὃ μονούμενον [15] αἱρετὸν ποιεῖ τὸν βίον καὶ μηδενὸς ἐνδεᾶ‧ τοιοῦτον δὲ τὴν εὐδαιμονίαν οἰόμεθα εἶναι‧ ἔτι δὲ πάντων αἱρετωτάτην μὴ συναριθμουμένην—συναριθμουμένην δὲ δῆλον ὡς αἱρετωτέραν μετὰ τοῦ ἐλαχίστου τῶν ἀγαθῶν‧ ὑπεροχὴ γὰρ ἀγαθῶν γίνεται τὸ προστιθέμενον, ἀγαθῶν δὲ τὸ μεῖζον αἱρετώτερον [20] ἀεί. τέλειον δή τι φαίνεται καὶ αὔταρκες ἡ εὐδαιμονία, τῶν πρακτῶν οὖσα τέλος.

[1097b] Honor, pleasure, nous and all the virtues we choose through themselves (for without anything further turning out, we would choose each of these). We also choose them for the sake of eudaimonia, 5 and through them pursue eudaimonia. No one for the sake of them chooses eudaimonia, which is not complete through another thing. The same conclusion also appears from its [eudaimonia’s] self-sufficiency, for it seems that the complete good is self-sufficient. We say that this self-sufficient [active good] is not in being solitary, living a solitary life, but also in parents, 10 children and women, and complete in friends and citizens, since humans are political by nature. For these, some boundary is taken, for, extending as far as their parents and their children and the friends of friends is to go ad infinitum. This is addressed later. We place the self-sufficient [good], which is singular, 15 as producing the chosen life; no one [who has this good] is deficient. We think eudaimonia is of this sort. Yet [we are] not enumerating it as a most chosen thing of all. It is clear that it is not more chosen with an addition of the least of the goods; for [then] the conjunction becomes the supreme of goods, [since] of goods the chosen thing is greater 20 always. In fact, eudaimonia appears to be something complete and self-sufficient, being the end of actions.

ἔργον argument!

Ἀλλ’ ἴσως τὴν μὲν εὐδαιμονίαν τὸ ἄριστον λέγειν ὁμολογούμενόν τι φαίνεται, ποθεῖται δ’ ἐναργέστερον τί ἐστιν ἔτι λεχθῆναι. τάχα δὴ γένοιτ’ ἂν τοῦτ’, εἰ ληφθείη τὸ ἔργον [25] τοῦ ἀνθρώτου. ὥσπερ γὰρ αὐλητῇ καὶ ἀγαλματοποιῷ καὶ παντὶ τεχνίτῃ, καὶ ὅλως ὦν ἔστιν ἔργον τι καὶ πρᾶξις, ἐν τῷ ἔργῳ δοκεῖ τἀγαθὸν εἶναι καὶ τὸ εὖ, οὕτω δόξειεν ἂν καὶ ἄνθρώπῳ, εἴπερ ἔστι τι ἔργον αὐτοῦ. πότερον οὖν τέκτονος μὲν καὶ σκυτέως ἔστιν ἔργα τινὰ καὶ πράξεις, ἀνθρώπου δ’ [30] οὐδέν ἐστιν, ἀλλ’ ἀργὸν πέφυκεν; ἢ καθάπερ ὀφθαλμοῦ καὶ χειρὸς καὶ ποδὸς καὶ ὅλως ἑκάστου τῶν μορίων φαίνεταί τι ἔργον, οὕτω καὶ ἀνθρώπου παρὰ πάντα ταῦτα θείη τις ἂν ἔργον τι; τί οὖν δὴ τοῦτ’ ἂν εἴη ποτέ; τὸ μὲν γὰρ ζῆν κοινὸν εἶναι φαίνεται καὶ τοῖς φυτοῖς, ζητεῖται δὲ τὸ ἴδιον. ‘φοριστέον [1098a] ἄρα τήν τε θρεπτικὴν καὶ τὴν αὐξητικὴν ζωήν. ἑπομένη δὲ αἰσθητική τις ἂν εἴη, φαίνεται δὲ καὶ αὐτὴ κοινὴ καὶ ἵππῳ καὶ βοὶ καὶ παντὶ ζῴῳ. λείπεται δὴ πρακτική τις τοῦ λόγον ἔχοντος‧ τούτου δὲ τὸ μὲν ὡς ἐπιπειθὲς λόγῳ, τὸ δ’ ὡς [5] ἔχον καὶ διανοούμενον. διττῶς δὲ καὶ τάυτης λεγομένης τὴν κατ’ ἐνέργειαν θετέον‧ κυριώτερον γὰρ αὕτη δοκεῖ λέγεσθαι. εἰ δ’ ἐστὶν ἔργον ἀνθρώπου ψυχῆς ἐνέργεια κατὰ λόγον ἢ μὴ ἄνευ λόγου, τὸ δ’ αὐτό φαμεν ἔργον εἶναι τῷ γένει τοῦδε καὶ τοῦδε σπουδαίου, ὥσπερ κιθαριστοῦ καὶ σπουδαίου [10] κιθαριστοῦ, καὶ ἁπλῶς δὴ τοῦτ’ ἐπὶ πάντων, προστιθεμένης τῆς κατὰ τὴν ἀρετὴν ὑπεροχῆς πρὸς τὸ ἔργον‧ κιθαριστοῦ μὲν γὰρ κιθαρίζειν, σπουδαίου δὲ τὸ εὖ‧ εἰ δ’ οὕτως, [ἀνθρώπου δὲ τίθεμεν ἔργον ζωήν τινα, ταύτην δὲ ψυχῆς ἐνέργειαν καὶ πράξεις μετὰ λόγου, σπουδαίου δ’ ἀνδρὸς εὖ ταῦτα καὶ [15] καλῶς, ἕκαστον δ’ εὖ κατὰ τὴν οἰκείαν ἀρετὴν ἀποτελεῖται‧ εἰ δ’ οὕτω] τὸ ἀνθρώπινον ἀγαθὸν ψυχῆς ἐνέργεια γίνεται κατ’ ἀρετήν, εἰ δ’ ἐν βίῳ τελείῳ. μία γὰρ χελιδὼν ἔαρ οὐ ποιεῖ, οὐδὲ μία ἡμέρα‧ οὕτω δὲ οὐδὲ μακάριον καὶ εὐδαίμονα [20] μία ἡμέρα οὐδ’ ὀλίγος χρόνος.

[1097b22] But perhaps it appears that to say that the best thing is eudaimonia is something agreed, and something more palpable is desired to still be said. So perhaps this would be more palpable, if the function 25 of human beings should be taken up. Since, just as for the aulos maker, the sculptor, and craftspeople, and all else for which there is some function and action, it seems that the good in the function is in doing it well. Thus it would also seem for human beings, if indeed there is some function of them. Then, is it the case that there is some function and action of the wood worker and of the leather worker but 30 there is not [some function] of human beings but [they are] by nature functionless? Or [is it the case that] just as some function appears of each of all the parts, i.e. of eyes, of hands and of feet, thus also there would be some function of human beings? The thing common to living things appears to be so also with respect to plants; and we seek the function particular [to human beings]. Separate, [1098a] it seems, [the human function is] from nutrition and growth. An aesthetic life would follow, but it appears that the same is common also in horse, ox, and all animals. An active life that has reason, then, is left; of this, there is that which is obedient to reason and that which 5 has and thinks through reason. And doubly, this active life is also said to be set according to activity, for this seems to be spoken of as more authoritative. And if the function of human beings is an activity of the soul according to reason or not without reason, and if we say the function is the same as this kind and is this excellence, just as of a cithara player [the function is] also to be an excellent 10 cithara player. Also without qualification, then, this is the case for all; the superiority [of the excellent one] is according to the virtue (ἀρετή) in addition to the function. For, the function of a cithara player is to play the cithara, but the function of an excellent cithara player is to play it well. And if so, and we place the function of a human being as something alive, this as an activity of the soul and action with reason, the function of an excellent human being is [to do] this well and 15 nobly, and each [function] is completed well according to its suitable virtue… and if so, then the human good becomes an activity of the soul according to virtue, if [the human good] is an end in life. For one swallow does not make a spring; nor one day. And in this way, neither blessed nor eudaimonious 20 does one day [make], nor a short time.

Περιγεγράφθω μὲν οὖν τἀγαθὸν ταύτῃ‧ δεῖ γὰρ ἴσως ὑποτυπῶσαι πρῶτον, εἶθ’ ὑστερον ἀναγράψαι. δόξειε δ’ ἂν παντὸς εἶναι προαγαγεῖν καὶ διαρθρῶσαι τὰ καλῶς ἔχοντα τῇ περιγραφῇ, καὶ ὁ χρόνος τῶν τοιούτων εὑρετὴς ἢ συνεργὸς ἀγαθὸς εἶναι‧ ὅθεν καὶ τῶν τεχνῶν [25] γεγόνασιν αἱ ἐπιδόσεις‧ παντὸς γὰρ προσθεῖναι τὸ ἐλλεῖπον. μεμνῆσθαι δὲ καὶ τῶν προειρημένων χρή, καὶ τὴν ἀκρίβειαν μὴ ὁμοίως ἐν ἅπασιν ἐπιζητεῖν, ἀλλ’ ἐν ἑκάστοις κατὰ τὴν ὑποκειμένην ὕλην καὶ ἐπὶ τοσοῦτον ἐφ’ ὅσον οἰκεῖον τῇ μεθόδῳ. καὶ γὰρ τέκτων καὶ γεωμέτρης διαφερόντως [30] ἐπιζητοῦσι τὴν ὀρθήν‧ ὅ μὲν γὰρ ἐφ’ ὅσον χρησίμη πρὸς τὸ ἔργον, ὃ δὲ τί ἐστιν ἢ ποῖόν τι‧ θεατὴς γὰρ τἀληθοῦς. τὸν αὐτὸν δὴ τρόπον καὶ ἐν τοῖς ἄλλοις ποιητέον, ὅπως μὴ τὰ πάρεργα τῶν ἔργων πλείω γίνηται. οὐκ ἀπαιτητέον [1098b] δ’ οὐδὲ τὴν αἰτίαν ἐν ἅπασιν ὁμοίως, ἀλλ’ ἱκανὸν ἔν τισι τὸ ὅτι δειχθῆναι καλῶς, οἷον καὶ περὶ τὰς ἀρχάς‧ τὸ δ’ ὅτι πρῶτον καὶ ἀρχή. τῶν ἀρχῶν δ’ αἵ μὲν ἐπαγωγῇ θεωροῦνται, αἵ δ’ αἰσθήσει, αἵ δ’ ἐθισμῷ τινί, καὶ ἄλλαι δ’ ἄλλως. μετιέναι [5] δὲ πειρατέον ἑκάστας ᾗ πεφύκασιν, καὶ σπουδαστέον ὅπως διορισθῶσι καλῶς‧ μεγάλην γὰρ ἔχουσι ῥοπὴν πρὸς τὰ ἑπόμενα. δοκεῖ γὰρ πλεῖον ἢ ἥμισυ τοῦ παντὸς εἶναι ἡ ἀρχή, καὶ πολλὰ συμφανῆ γίνεσθαι δι’ αὐτῆς τῶν ζητουμένων.

Then let us have drawn an outline for the good. Since it is perhaps necessary to first sketch it out and then to fill it in. It would seem that all people with a good outline may go on and articulate the things that are noble and that the time spent on these sorts of things would lead to discovery or good work, through which also for crafts 25 advances have been born, for all can add what is missing. It is necessary to recall also of the things having been said earlier, to seek after exactness in all things not in the same way, but in each thing according to the underlying material and as much as is appropriate to the sort of inquiry at hand. For both a wood worker and a geometer in different ways 30 seek the right angle, for the former seeks [it] as far as it is useful for his work, and the latter seeks what it is or of what sort it is, for the geometer a spectator of truth. In fact, we must do in the same way also in the others, so as to not make the subordinate things of the works become much more. We must not demand [1098b] similarly in all for the cause, but [in the way] befitting the thing that is to be shown. For instance, concerning the starting points (ἀρχή, principle), that which is the first starting point. Of the starting points, some are grasped by induction, some by the senses, some by some habituation, and others in another way. We must go after 5 each one that has been brought forth and take [them] seriously in such a way to determine [them] well, for they have a great impact on the things that follow. For it seems that the starting point is a large part or half of all of [an inquiry?], and much become manifest through them of the things being sought.

Chapter 8:

Σκεπτέον δὲ περὶ αὐτῆς οὐ μόνον ἐκ τοῦ συμπεράσματος [10] καὶ ἐξ ὧν ὁ λόγος, ἀλλὰ καὶ ἐκ τῶν λεγομένων περὶ αὐτῆς‧ τῷ δὲ ψευδεῖ ταχὺ διαφωνεῖ τἀληθές. νενεμημένων δὴ τῶν ἀγαθῶν τριχῇ, καὶ τῶν μὲν ἐκτὸς λεγομένων τῶν δὲ περὶ ψυχὴν καὶ σῶμα, τὰ περὶ ψυχὴν κυριώτατα λέγομεν καὶ [15] μάλιστα ἀγαθά, τὰς δὲ πράξεις καὶ τὰς ἐνεργείας τὰς ψυχικὰς περὶ ψυχὴν τίθεμεν. ὥστε καλῶς ἂν λέγοιτο κατά γε ταύτην τὴν δόξαν παλαιὰν οὖσαν καὶ ὁμολογουμένην ὑπὸ τῶν φιλοσοφούντων. ὀρθῶς δὲ καὶ ὅτι πράξεις τινὲς λέγονται καὶ ἐνέργειαι τὸ τέλος‧ οὕτω γὰρ τῶν περὶ ψυχὴν ἀγαθῶν [20] γίνεται καὶ οὐ τῶν ἐκτός. συνᾴδει δὲ τῷ λόγῳ καὶ τὸ εὖ ζῆν καὶ τὸ εὖ πράττειν τὸν εὐδαίμονα‧ σχεδὸν γὰρ εὐζωία τις εἴρηται καὶ εὐπραξία.

[1098b9] The argument must be viewed concerning the ἀρχή not only from the conclusion 10 and from the things from which it followed but also from the things that have been said concerning it; [since] the truth is quickly dissonant with the false. In fact the goods have been divided in three ways; it is said there are external goods, goods concerning the soul and goods concerning the body. We say the ones of the soul are most authoritative 15 and good most of all, and we place the actions and activities of the soul in the soul. Just as it would well be said according to this ancient δόξα, which is agreed upon by the ones who philosophize. It is also correctly said that the end consists in some actions and activities, for it becomes of the things concerning good of the soul 20 and not of the external goods. And with reason do living well and acting well according to eudaimonia sing, for living well and acting well have closely be said.

Φαίνεται δὲ καὶ τὰ ἐπιζητούμενα τὰ περὶ τὴν εὐδαιμονίαν ἅπανθ’ ὑπάρχειν τῷ λεχθέντι. τοῖς μὲν γὰρ ἀρετὴ τοῖς δὲ φρόνησις ἄλλοις δὲ σοφία τις εἶναι δοκεῖ, [25] τοῖς δὲ ταῦτα ἢ τούτων τι μεθ’ ἡδονῆς ἢ οὐκ ἄνευ ἡδονῆς‧ ἕτεροι δὲ καὶ τὴν ἐκτὸς εὐετηρίαν συμπαραλαμβάνουσιν. τούτων δὲ τὰ μὲν πολλοὶ καὶ παλαιοὶ λέγουσιν, τὰ δὲ ὀλίγοι καὶ ἔνδοξοι ἄνδρες‧ οὐδετέρους δὲ τούτων εὔλογον διαμαρτάνειν τοῖς ὅλοις, ἀλλ’ ἕν γέ τι ἢ καὶ τὰ πλεῖστα κατορθοῦν. [30] τοῖς μὲν οὖν λέγουσι τὴν ἀρετὴν ἢ ἀρετήν τινα συνῳδός ἐστιν ὁ λόγος‧ ταύτης γάρ ἐστιν ἡ κατ’ αὐτὴν ἐνέργεια. διαφέρει δὲ ἴσως οὐ μικρὸν ἐν κτήσει ἢ χρήσει τὸ ἄριστον ὑπολαμβάνειν, καὶ ἐν ἕξει ἢ ἐνεργείᾳ. τὴν μὲν γὰρ ἕξιν ἐνδέχεται [1099α] μηδὲν ἀγαθὸν ἀποτελεῖν ὑπάρχουσαν, οἷον τῷ καθεύδοντι ἢ καὶ ἄλλως πως ἐξηργηκότι, τὴν δ’ ἐνέργειαν οὐχ οἷόν τε‧ πράξει γὰρ ἐξ ἀνάγκης, καὶ εὖ πράξει. ὥσπερ δ’ ‘Ολυμπίασιν οὐχ οἱ κάλλιστοι καὶ ἰσχυρότατοι στεφανοῦνται ἀλλ’ [5] οἱ ἀγωνιζόμενοι (τούτων γάρ τινες νικῶσιν), οὕτω καὶ τῶν ἐν τῷ βίῳ καλῶν κἀγαθῶν οἱ πράττοντες ὀρθῶς ἐπήβολοι γίνονται. ἔστι δὲ καὶ ὁ βίος αὐτῶν καθ’ αὑτὸν ἡδύς. τὸ μὲν γὰρ ἥδεσθαι τῶν ψυχικῶν, ἑκάστῳ δ’ ἐστὶν ἡδὺ πρὸς ὃ λέγεται φιλοτοιοῦτος, οἷον ἵππος μὲν τῷ φιλίππῳ, θέαμα [10] δὲ τῷ φιλοθεῶρῳ‧ τὸν αὐτὸν δὲ τρόπον καὶ τὰ δίκαια τῷ φιλοδικαίῳ καὶ ὅλως τὰ κατ’ ἀρετὴν τῷ φιλαρέτῳ. τοῖς μὲν οὖν πολλοῖς τὰ ἡδέα μάχεται διὰ τὸ μὴ φύσει τοιαῦτ’ εἶναι, τοῖς δὲ φιλοκάλοις ἐστὶν ἡδέα τὰ φύσει ἡδέα‧ τοιαῦται δ’ αἱ κατ’ ἀρετὴν πράξεις, ὥστε καὶ τούτοις εἰσὶν ἡδεῖαι καὶ [15] καθ’ αὑτάς. οὐδὲν δὴ προσδεῖται τῆς ἡδονῆς ὁ βίος αὐτῶν ὥσπερ περιάπτου τινός, ἀλλ’ ἔχει τὴν ἡδονὴν ἐν ἑαυτῷ. πρὸς τοῖς εἰρημένοις γὰρ οὐδ’ ἐστὶν ἀγαθὸς ὁ μὴ χαίρων ταῖς καλαῖς πράξεσιν‧ οὔτε γὰρ δίκαιον οὐθεὶς ἂν εἴποι τὸν μὴ χαίροντα τῷ δικαιοπραγεῖν, οὔτ’ ἐλευθέριον τὸν μὴ χαίροντα [20] ταῖς ἐλευθερίοις πράξεσιν‧ ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ ἐπὶ τῶν ἄλλων. εἰι δ’ οὕτω, καθ’ αὑτὰς ἂν εἶεν αἱ κατ’ ἀρετὴν πράξεις ἡδεῖαι. ἀλλὰ μὴν καὶ ἀγαθαί γε καὶ καλαί, καὶ μάλιστα τούτων ἕκαστον, εἴπερ καλῶς κρίνει περὶ αὐτῶν ὁ σπουδαῖος‧ κρίνει δ’ ὡς εἴπομεν. ἄριστον ἄρα καὶ κάλλιστον καὶ ἥδιστον ἡ [25] εὐδαιμονία, καὶ οὐ διώρισται ταῦτα κατὰ τὸ Δηλιακὸν ἐπίγραμμα‧

It appears that the things being sought after concerning eudaimonia has all already been laid down. For it seems to some to be virtue, to others φρόνησις, and to others, wisdom. 25 To others it seems to be [all of] these or some of these with pleasure or [at least] not without pleasure. And others take eudaimonia to be something with external prosperity. Of these, some the many and ancients assert, others the few and well-regarded men assert. And neither of the two go astray with respect to the whole, but some part of even a large part is right. 30 The argument is in harmony with those saying that the good is virtue or some virtue, for the good is activity according to it. And perhaps it makes a difference not in a small way (huge, haha) to understand the best thing as consisting in acquisition or in use, i.e. as consisting in a state or in an activity. For on the one hand it is possible [1099a] that the existence of a state does not [entail] production of a good. For example, when one is asleep or even in other ways having been neglected. On the other hand this is not the case for an activity, for it necessarily entails acting, and to act well. And just as in the Olympic games the strongest and mightiest are not crowned, but 5 the ones competing for a prize (for only some of these [athletes] may win), thus also the ones who have achieved acting correctly become the ones who [are crowned] the noble and good life. And the life of these [people] is also sweet according to itself. For taking pleasure is of the parts of the soul, and for each, sweet is that towards which one is fond. For example, a horse for the lover of horses, a spectacle 10 for a lover of spectacles. In the same way, also justices by the lover of justice, and in short the things according to virtue by the lover of virtue. In the many, then, the pleasurable things fight in different directions [because they] are not by nature such as this; in the one who love the noble, the pleasures are sweet by nature. And the actions according to virtue are such as this, [i.e. sweet], such that they are both sweet to them [i.e. the ones doing them] and 15 according to themselves. In fact, their life does not at all need pleasure as some ornament but has pleasure in itself. For, besides the things that have been said, one is not good if one does not take pleasure in noble actions, for no one would say one is just if one does not enjoy doing just things, nor free if one does not enjoy 20 doing free things, and similarly also in the case with the others. If so, the actions according to virtue would be sweet according to themselves. But [they would also be] both good and noble, if indeed the excellent man most of all with respect to each judges well, as we [already] said he judges. So best, i.e. most noble and most sweet, is 25 eudaimonia, and these [characteristics] have not been separated like in the Delos epigram:

κάλλιστον τὸ δικαιότατον, λῷστον δ’ ὑγιαίνειν‧

ἥδιστον δὲ πέφυχ’ οὗ τις ἐρᾷ τὸ τυχεῖν.

most noble is the most just, and most desirable is being healthy

but most sweet is having brought forth that which one loves to get.

ἅπαντα γὰρ ὑπάρχει ταῦτα ταῖς ἀρίσταις ἐνεργείαις‧ ταύτας [30] δέ, ἢ μίαν τούτων τὴν ἀρίστην, φαμὲν εἶναι τὴν εὐδαιμονίαν. φαίνεται δ’ ὅμως καὶ τῶν ἐκτὸς ἀγαθῶν προσδεομένη, καθάπερ εἴπομεν‧ ἀδύνατον γὰρ ἢ οὐ ῥᾴδιον τὰ καλὰ πράττειν ἀχορήγητον ὄντα. πολλὰ μὲν γὰρ πράττεται, [1099b] καθάπερ δι’ ὀργάνων διὰ φίλων καὶ πλούτου καὶ πολιτικῆς δυνάμεως‧ ἐνίων δὲ τητώμενοι ῥυπαίνουσι τὸ μακάριον, οἷον εὐγενείας εὐτεκνίας κάλλους‧ οὐ πάνυ γὰρ εὐδαιμονικὸς ὁ τὴν ἰδέαν παναίσχης ἢ δυσγενὴς ἢ μονώτης καὶ ἄτεκνος, [5] ἔτι δ’ ἴσως ἧττον, εἴ τῳ πάγκακοι παῖδες εἶεν ἢ φίλοι, ἢ ἀγαθοὶ ὄντες τεθνᾶσιν. καθάπερ οὖν εἴπομεν, ἔοικε προσδεῖσθαι καὶ τῆς τοιαύτης εὐημερίας‧ ὅθεν εἰς ταὐτὸ τάττουσιν ἔνιοι τὴν εὐτυχίαν τῇ εὐδαιμονίᾳ, ἕτεροι δὲ τὴν ἀρετήν.

For quite all these [characteristics] belong to the best activities, and we say eudaimonia is with respect to these or with the best one of these. It appears also that generally, [eudaimonia] is in need of external goods, just as we said, for powerless or not easy is doing noble things without supplies. For one much one needs external goods [1099b] as tools, e.g. friends, wealth and political power. And being in want of some things defiles the blessed life. For example, noble birth, well-born children, and beauty. For not conducive to eudaimonia is being utterly ugly in form, nor being low-born, nor being solitary and childless. 5 Yet perhaps one is worse off, if one’s children would be utterly bad, or one’s friends; or if they are good, they are killed. Then, just as we said, it seems one also needs these sorts of good days. From the same, some assess eudaimonia as prosperity, others as virtue.

Chapter 9

Ὅθεν καὶ ἀπορεῖται πότερόν ἐστι μαθητὸν ἢ ἐθιστὸν ἢ καὶ [10] ἄλλως πως ἀσκητόν, ἢ κατά τινα θείαν μοῖραν ἢ καὶ διὰ τύχην παραγίνεται. εἰ μὲν οὖν καὶ ἄλλο τί ἐστι θεῶν δώρημα ἀνθρώποις, εὔλογον καὶ τὴν εὐδαιμονίαν θεόσδοτον εἶναι, καὶ μάλιστα τῶν ἀνθρωπίνων ὅσῳ βέλτιστον. ἀλλὰ τοῦτο μὲν ἴσως ἄλλης ἂν εἴη σκέψεως οἰκειότερον, φαίνεται δὲ κἂν εἰ [15] μὴ θεόπεμπτός ἐστιν ἀλλὰ δι’ ἀρετὴν καί τινα μάθησιν ἢ ἄσκησιν παραγίνεται, τῶν θειοτάτων εἶναι‧ τὸ γὰρ τῆς ἀρετῆς ἆθλον καὶ τέλος ἄριστον εἶναι φαίνεται καὶ θεῖόν τι καὶ μακάριον. εἴη δ’ ἂν καὶ πολύκοινον‧ δυνατὸν γὰρ ὑπάρξαι πᾶσι τοῖς μὴ πεπηρωμένοις πρὸς ἀρετὴν διά τινος μαθήσεως [20] καὶ ἐπιμελείας. εἰ δ’ ἐστὶν οὕτω βέλτιον ἢ τὸ διὰ τύχην εὐδαιμονεῖν, εὔλογον ἔχειν οὕτως, εἴπερ τὰ κατὰ φύσιν, ὡς οἷόν τε κάλλιστα ἔχειν, οὕτω πέφυκεν, ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ τὰ κατὰ τέχνην καὶ πᾶσαν αἰτίαν, καὶ μάλιστα {τὰ} κατὰ τὴν ἀρίστην. τὸ δὲ μέγιστον καὶ κάλλιστον ἐπιτρέψαι τύχῃ λίαν πλημμελὲς [25] ἂν εἴη. συμφανὲς δ’ ἐστὶ καὶ ἐκ τοῦ λόγου τὸ ζητούμενον‧ εἴρηται γὰρ ψυχῆς ἐνέργεια κατ’ ἀρετὴν ποιά τις. τῶν δὲ λοιπῶν ἀγαθῶν τὰ μὲν ὑπάρχειν ἀναγκαῖον, τὰ δὲ συνεργὰ καὶ χρήσιμα πέφυκεν ὀργανικῶς. ὁμολογούμενα δὲ ταῦτ’ ἂν εἴη καὶ τοῖς ἐν ἀρχῇ‧ τὸ γὰρ τῆς πολιτικῆς [30] τέλος ἄριστον ἐτίθεμεν, αὕτη δὲ πλείστην ἐπιμέλειαν ποιεῖται τοῦ ποιούς τινας καὶ ἀγαθοὺς τοὺς πολίτας ποιῆσαι καὶ πρακτικοὺς τῶν καλῶν. εἰκότως οὖν οὔτε βοῦν οὔτε ἵππον οὔτε ἄλλο τῶν ζῴων οὐδὲν εὔδαιμον λέγομεν‧ οὐδὲν γὰρ αὐτῶν [1100a] οἶόν τε κοινωνῆσαι τοιαύτης ἐνεργείας. διὰ ταύτην δὲ τὴν αἰτίαν οὐδὲ παῖς εὐδαίμων ἐστίν‧ οὔπω γὰρ πρακτικὸς τῶν τοιούτων διὰ τὴν ἡλικίαν‧ οἱ δὲ λεγόμενοι διὰ τὴν ἐλπίδα μακαρίζονται. δεῖ γάρ, ὥσπερ εἴπομεν, καὶ ἀρετῆς τελείας [5] καὶ βίου τελείου. πολλαὶ γὰρ μεταβολαὶ γίνονται καὶ παντοῖαι τύχαι κατὰ τὸν βίον, καὶ ἐνδέχεται τὸν μάλιστ’ εὐθηνοῦντα μεγάλαις συμφοραῖς περιπεσεῖν ἐπὶ γήρως, καθάπερ ἐν τοῖς Τρωικοῖς περὶ Πριάμου μυθεύεται‧ τὸν δὲ τοιαύταις χρησάμενον τύχαις καὶ τελευτήσαντα ἀθλίως οὐδεὶς εὐδαιμονίζει.

For the same reason it is also puzzling whether eudaimonia is something learned, acquired through habit or even 10 some other training, or fate according to some god or even brought about through fortune. If, then, there is some other gift of the gods to human beings, then it is reasonable that eudaimonia is also god-given, since it is of human affairs most of all best. But this perhaps would be more appropriate of another inquiry, and it appears also that even if 15 it is not sent by the gods but brought about through virtue and some learning or training, it is still of the most divine things, for the prize of virtue appears to also be the best end and something most divine and blessed. It would also seem common to many, for as long as one has not been mutilated, all are capable to begin towards virtue through some learning 20 and attention. And if it is better this way than to attain eudaimonia through fortune, it is reasonable in this way, if indeed the things according to nature, as to be most noble, has thus similarly also produced the things according to craft and all cause, and most of all according to virtue. And it would be very out of tune to entrust the greatest and most noble thing to fortune. 25 And it is also quite manifest from reason the thing being sought, for it has been said to be some activity of soul according to virtue of some kind. Of the remaining goods, some are necessary to begin, others work together with and are useful to serve as instruments. These [claims] would also be agreeable with the things [we said] in the beginning, for the end of politics 30 was set as the best, and this [was said] with respect to [its] making good citizens of some kind, [who are] active in noble things. It makes sense, then, that we do not call a cow, nor a horse, nor other animals eudimonious, for none of them [1100a] share in these sorts of activities. Through this same reason, neither [do we call] a child eudaimonious, for because of age it is not yet active of this sort. The ones we call eudaimonious are deemed such through hope. For [to call someone eudaimonious] it is necessary, just as we said, [to have] both complete virtue 5 and a complete life. For many changes happen, all sorts of fortunes during the course of a life, and it is possible that despite being the one flourishing most to fall because of great events in the time of old age, just as we speak of Priam in the time of Troy. And no one is eudaimonious if they experience these sorts of fortunes and end wretched.

Chapter 10

[10] Πότερον οὖν οὐδ’ ἄλλον οὐδένα ἀνθρώπων εὐδαιμονιστέον ἕως ἂν ζῇ, κατὰ Σόλωνα δὲ χρεὼν τέλος ὁρᾶν; εἰ δὲ δὴ καὶ θετέον οὕτως, ἆρά γε καὶ ἔστιν εὐδαίμων τότε ἐπειδὰν ἀποθάνῃ; ἢ τοῦτό γε παντελῶς ἄτοπον, ἄλλως τε καὶ τοῖς λέγουσιν ἡμῖν ἐνέργειάν τινα τὴν εὐδαιμονίαν; εἰ δὲ μὴ λέγομεν [15] τὸν τεθνεῶτα εὐδαίμονα, μηδὲ Σόλων τοῦτο βούλεται, ἀλλ’ ὅτι τηνικαῦτα ἄν τις ἀσφαλῶς μακαρίσειεν ἄνθρωπον ὡς ἐκτὸς ἤδη τῶν κακῶν ὄντα καὶ τῶν δυστυχημάτων, ἔχει μὲν καὶ τοῦτ’ ἀμφισβήτησίν τινα‧ δοκεῖ γὰρ εἶναί τι τῷ τεθνεῶτι καὶ κακὸν καὶ ἀγαθόν, εἴπερ καὶ τῷ ζῶντι μὴ [20] αἰσθανομένῳ δέ, οἶον τιμαὶ καὶ ἀτιμίαι καὶ τέκνων καὶ ὅλως ἀπογόνων εὐπραξίαι τε καὶ δυστυχίαι. ἀπορίαν δὲ καὶ ταῦτα παρέχει‧ τῷ γὰρ μακαρίως βεβιωκότι μέχρι γήρως καὶ τελευτήσαντι κατὰ λόγον ἐνδέχεται πολλὰς μεταβολὰς συμβαίνειν περὶ τοὺς ἐκγόνους, καὶ τοὺς μὲν αὐτῶν [25] ἀγαθοὺς εἶναι καὶ τυχεῖν βίου τοῦ κατ’ ἀξίαν, τοὺς δ’ ἐξ ἐναντίας‧ δῆλον δ’ ὅτι καὶ τοῖς ἀποστήμασι πρὸς τοὺς γονεῖς παντοδαπῶς ἔχειν αὐτοὺς ἐνδέχεται. ἄτοπον δὴ γίνοιτ’ ἄν, εἰ συμμεταβάλλοι καὶ ὁ τεθνεὼς καὶ γίνοιτο ὁτὲ μὲν εὐδαίμων πάλιν δ’ ἄθλιος‧ ἄτοπον δὲ καὶ τὸ μηδὲν μηδ’ ἐπί [30] τινα χρόνον συνικνεῖσθαι τὰ τῶν ἐκγόνων τοῖς γονεῦσιν. ἀλλ’ ἐπανιτέον ἐπὶ τὸ πρότερον ἀπορηθέν‧ τάχα γὰρ ἂν θεωρηθείη καὶ τὸ νῦν ἐπιζητούμενον ἐξ ἐκείνου.

10 Is it then the case that it is necessary not to call any human being eudaimonious so long as they would live, but as according to Solon, it is necessary to see the end? But if in fact it must thus be set, then is it really the case that one is eudaimonious at the time after one dies? Or is this in a way completely out of place for us who say that eudaimonia is some activity? And if we would not say 15 that someone who has been died is eudaimonious, and Solon isn’t wishing [to say] this, but [instead that] at the time of death someone would stably deem a person happy and as already outside [the reach] of bad things and of ill fotunes, then this also has some controversy, for it seems that [even after] having been killed, something [can be] both good and bad, if indeed even during one’s life things can be not 20 apprehended. For example, honors and dishonors, good conduct and ill fortune of one’s children and even one’s entire progeny. And these also provide an aporia, for [despite] having lived happily until old age and completed [one’s life] according to reason, it is possible that many changes [of fortune] happen to one’s descendants; some of them 25 are good and live a life according to [their] worth, others the opposite. And it is clear that it is also possible for [one’s descendants] to be in various relationships with respect to their ancestors. In fact it would be strange if the [fortune of the] one who has [already] died would also change with [these descendants’] and one would be at some time [considered] happy [and at another time] back to [being considered] wretched. [It would] also be strange [if] 30 the affairs of the descendants pertain not at all to the ancestors. But we must return to the first question, for perhaps it would be helpful for what we now seek [which is originally] from that.

εἰ δὴ τὸ τέλος ὁρᾶν δεῖ καὶ τότε μακαρίζειν ἕκαστον οὐχ ὡς ὀντα μακάριον ἀλλ’ ὅτι πρότερον ἦν πῶς οὐκ ἄτοπον, εἰ ὅτ’ ἔστιν εὐδαίμων, [35] μὴ ἀληθεύσεται κατ’ αὐτοῦ τὸ ὑπάρχον διὰ τὸ μὴ [1100b] βούλεσθαι τοὺς ζῶντας εὐδαιμονίζειν διὰ τὰς μεταβολάς, καὶ διὰ τὸ μόνιμόν τι τὴν εὐδαιμονίαν ὑπειληφέναι καὶ μηδαμῶς εὐμετάβολον, τὰς δὲ τύχας πολλάκις ἀνκυκλεῖσθαι περὶ τοὺς αὐτούς; δῆλον γὰρ ὡς εἰ συνακολουθοίημεν [5] ταῖς τύχαις, τὸν αὐτὸν εὐδαίμονα καὶ πάλιν ἄθλιον ἐροῦμεν πολλάκις, χαμαιλέοντά τινα τὸν εὐδαίμονα ἀποφαίνοντες καὶ σαθρῶς ἱδρυμένον. ἢ τὸ μὲν ταῖς τύχαις ἐπακολουθεῖν οὐδαμῶς ὀρθόν; οὐ γὰρ ἐν ταύταις τὸ εὖ ἢ κακῶς, ἀλλὰ προσδεῖται τούτων ὁ ἀνθρώπινος βίος, καθάπερ εἴπομεν, κύριαι [10] δ’ εἰσὶν αἱ κατ’ ἀρετὴν ἐνέργειαι τῆς εὐδαιμονίας, αἱ δ’ ἐναντίαι τοῦ ἐναντίου. μαρτυρεῖ δὲ τῷ λογῳ καὶ τὸ νῦν διαπορηθέν. περὶ οὐδὲν γὰρ οὕτως ὑπάρχει τῶν ἀνθρωπίνων ἔργων βεβαιότης ὡς περὶ τὰς ἐνεργείας τὰς κατ’ ἀρετήν‧ μονιμώτεραι γὰρ καὶ τῶν ἐπιστημῶν αὗται δοκοῦσιν εἶναι‧ [15] τούτων δ’ αὐτῶν αἱ τιμιώταται μονιμώτεραι διὰ τὸ μάλιστα καὶ συνεχέστατα καταζῆν ἐν αὐταῖς τοὺς μακαρίους‧ τοῦτο γὰρ ἔοικεν αἰτίῳ τοῦ μὴ γίνεσθαι περὶ αὐτὰς λήθην. ὑπάρξει δὴ τὸ ζητουμενον τῷ εὐδαίμονι, καὶ ἔσται διὰ βίου τοιοῦτος‧ ἀεὶ γὰρ ἢ μάλιστα πάντων πράξει καὶ θεωρήσει [20] τὰ κατ’ ἀρετήν, καὶ τὰς τύχας οἴσει κάλλιστα καὶ πάντῃ πάντως ἐμμελῶς ὅ γ’ ὡς ἀληθῶς ἀγαθὸς καὶ τετράγωνος ἄνευ ψόγου. πολλῶν δὲ γινομένων κατὰ τύχην καὶ διαφερόντων μεγέθει καὶ μικρότητι, τὰ μὲν μικρὰ τῶν εὐτυχημάτων, ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ τῶν ἀντικειμένων, δῆλον ὡς οὐ ποιεῖ [25] ῥοπὴν τῆς ζωῆς, τὰ δὲ μεγάλα καὶ πολλὰ γιωόμενα μὲν εὖ μακαριώτερον τὸν βίον ποιήσει (καὶ γὰρ αὐτὰ συνεπικοσμεῖν πέφυκεν, καὶ ἡ χρῆσις αὐτῶν καλὴ καὶ σπουδαία γίνεται), ἀνάπαλιν δὲ συμβαίνοντα θλίβει καὶ λυμαίνεται τὸ μακάριον‧ λύπας τε γὰρ ἐπιφέρει καὶ ἐμποδίζει πολλαῖς [30] ἐνεργείαις. ὅμως δὲ καὶ ἐν τούτοις διαλάμπει τὸ καλόν, ἐπειδὰν φέρῃ τις εὐκόλως πολλὰς καὶ μεγάλας ἀτυχίας, μὴ δι’ ἀναλγησίαν, ἀλλὰ γεννάδας ὢν καὶ μεγαλόψυχος. εἰ δ’ εἰσὶν αἱ ἐνέργειαι κύριαι τῆς ζωῆς, καθάπερ εἴπομεν, οὐδεὶς ἂν γένοιτο τῶν μακαρίων ἄθλιος‧ οὐδέποτε [35] γὰρ πράξει τὰ μισητὰ καὶ τὰ φαῦλα. τὸν γὰρ ὡς ἀληθῶς [1101a] αγαθὸν καὶ ἔμφρονα πάσας οἰόμεθα τὰς τύχας εὐσχημόνως φέρειν καὶ ἐκ τῶν ὑπαρχόντων ἀεὶ τὰ κάλλιστα πράττειν, καθάπερ καὶ στρατηγὸν ἀγαθὸν τῷ παρόντι στρατοπέδῳ χρῆσθαι πολεμικώτατα καὶ σκυτοτόμον ἐκ τῶν δοθέντων [5] σκυτῶν κάλλιστον ὑπόδημα ποιεῖν‧ τὸν αὐτὸν δὲ τρόπον καὶ τοὺς ἄλλους τεχνίτας ἅπαντας. εἰ δ’ οὕτως, ἄθλιος μὲν οὐδέποτε γένοιτ’ ἂν ὁ εὐδαίμων, οὐ μὴν μακάριός γε, ἂν Πριαμικαῖς τύχαις περιπέσῃ. οὐδὲ δὴ ποικίλος γε καὶ εὐμετάβολος‧ οὔτε γὰρ ἐκ τῆς εὐδαιμονίας κινηθήσεται ῥᾳδίως, [10] οὐδ’ ὑπὸ τῶν τυχόντων ἀτυχημάτων ἀλλ’ ὑπὸ μεγάλων καὶ πολλῶν ἔκ τε τῶν τοιούτων οὐκ ἂν γένοιτο πάλιν εὐδαίμων ἐν ὀλίγῳ χρόνῳ, ἀλλ’ εἴπερ, ἐν πολλῷ τινὶ καὶ τελείῳ, μεγάλων καὶ καλῶν ἐν αὐτῷ γενόμενος ἐπήβολος. τί οὖν κωλύει λέγειν εὐδαίμονα τὸν κατ’ ἀρετὴν τελείαν [15] ἐνεργοῦντα καὶ τοῖς ἐκτὸς ἀγαθοῖς ἱκανῶς κεχορηγημένον μὴ τὸν τυχόντα χρόνον ἀλλὰ τέλειον βίον; ἢ προσθετέον καὶ βιωσόμενον οὕτω καὶ τελευτήσοντα κατὰ λόγον; επειδὴ τὸ μέλλον ἀφανὲς ἡμῖν ἐστίν, τὴν εὐδαιμονίαν δὲ τέλος καὶ τέλειον τίθεμεν πάντῃ πάντως. εἰ δ’ οὕτω, μακαρίους ἐροῦμεν [20] τῶν ζώντων οἷς ὑπάρχει καὶ ὑπάρξει τὰ λεχθέντα, μακαρίους δ’ ἀνθρώπους. καὶ περὶ μὲν τούτων ἐπὶ τοσοῦτον διωρίσθω.

If, then, it is necessary to see the end and to deem each [person] at that time not as being blessed but [as] that they were blessed earlier, how is it not out of place, if that is eudaimonious, 35 i.e. if one will not truthfully call them [blessed] if during their lives due to not [1100b] wanting to call blessed the living ones because of the [possible] changes [in fortune] and due to [understanding it as] some stable thing, to have understood eudaimonia also as not changeable and the fortunes [do] turn around again many times around them? For it is thus clear that if we followed 5 the fortunes closely, we would say that the same man is eudaimonious and back as wretched many times, making eudaimonia into some chameleon and having settled it unsoundly. Or is closely following the fortunes not right? For not in these is doing well or badly, but the human life needs things besides these, just as we said. Proper 10 are the activities according to virtue for eudaimonia, and the opposites for the opposite [wretchedness]. And the present discussion bears witness by reason, since in the case of nothing else is there an assurance in this way of the works of humans as in the case of activities in accordance with virtue. For these seem to be more stable than even scientific knowledge (ἐπιστήμη). 15 The most valued of these themselves seem to be more stable because the blessed ones live on most and hold most together in these [activities in accordance with virtue], for this [doing these] looks like a cause for it not being forgotten. The thing being sought, then, will exist with the blessed person and they will live through a life of this sort, for the things in accordance with virtue 20 are always or most of all [found in] actions and contemplations. They, who are truly good and are tetragonal without blemish, will bear the fortunes most beautifully and in ways wholly in tune. And many things come to be according to fortunes and differ both great and small. Some are small pieces of good fortune, and similarly [small] also the opposites. It is clear that [these small things] do not make 25 a turn of the scale for a living thing. Others are large [pieces of fortune] and many of them happening in a good way make for a more blessed life, for they themselves also embellish, and the experience of them becomes noble and excellent. But the reverse happening pinches and outrages the blessed thing, for it brings and fetters pain of body in many 30 activities.Nevertheless, also in these cases the noble one shines through, since someone [noble] would contently bear many and large misfortunes, not through insensibility but [through] being noble, i.e. magnanimous. And if the activities are proper to the living, just as we said, no one would become wretched from blessed things, for never 35 will he do hateful nor simple things. For with respect to the true [1101a] good, we think that in their minds all [with the good] bear the fortunes gracefully and always do the most noble things in the circumstances, just as also a good general in the present encampment executes things in the most skillful way in war, and a shoemaker from the given 5 hide makes sandals in the most beautiful way. And in the same way also are quite all the other craftsmen. And if thus, never wretched would the eudaimonious person become, [though] certainly not blessed, if they were to encounter Priam’s misfortunes. Nor in fact [will they be] wily and changing, for they will not be moved from the eudaimonious life easily, 10 not by coincidental misfortunes, but [only] by great and many [misfortunes], from these sorts of things they would not return as being eudaimonious in a short period of time, but if indeed [they are], in some many ends, they become to have achieved great and noble things. What then, prevents saying that eudaimonia is the life of acting according to a virtuous end 15 and sufficiently having been furnished with external goods, not for a coincidental time but for a complete life? Or is it necessary to add also thus to live intending to accomplish it according to reason? Since the future is to us unclear, we place eudaimonia [as] a complete end for all completely. And if thus, we will say, 20 of those living who exist and will exist according to the things we have said, as blessed people. And concerning these, let us have to here drawn a boundary.

Chapter 11

[1101a22] Τὰς δὲ τῶν ἀπογόνων τύχας καὶ τῶν φίλων ἁπάντων τὸ μὲν μηδοτιοῦν συμβάλλεσθαι λίαν ἄφιλον φαίνεται καὶ ταῖς δόξαις ἐναντίον‧ πολλῶν δὲ καὶ παντοίας ἐχόντων διαφορὰς [25] τῶν συμβαινόντων, καὶ τῶν μὲν μᾶλλον συνικνουμένων τῶν δ’ ἧττον, καθ’ ἕκαστον μὲν διαιρεῖν μακρὸν καὶ ἀπέραντον φαίνεται, καθόλου δὲ λεχθὲν καὶ τύπῳ τάχ’ ἂν ἱκανῶς ἔχοι. εἰ δή, καθάπερ καὶ τῶν περὶ αὑτὸν ἀτυχημάτων τὰ μὲν ἔχει τι βρῖθος καὶ ῥοπὴν πρὸς τὸν βίον τὰ [30] δ’ ἐλαφροτέροις ἔοικεν, οὕτω καὶ τὰ περὶ τοὺς φίλους ὁμοίως ἅπαντας, διαφέρει δὲ τῶν παθῶν ἕκαστον περὶ ζῶντας ἢ τελευτήσαντας συμβαίνειν πολὺ μᾶλλον ἢ τὰ παράνομα καὶ δεινὰ προΰπαρχειν ἐν ταῖς τραγῳδίαις ἢ πράττεσθαι, συλλογιστέον δὴ καὶ ταύτην τὴν διαφοράν, μᾶλλον δ’ ἴσως τὸ διαπορεῖσθαι περὶ τοὺς κεκμηκότας εἴ τινος ἀγαθοῦ κοινωνοῦσιν [1101b] ἢ τῶν ἀντικειμένων. ἔοικε γὰρ ἐκ τούτων εἰ καὶ διικνεῖται πρὸς αὐτοὺς ὁτιοῦν, εἴτ’ ἀγαθὸν εἴτε τοὐναντίον, ἀφαυρόν τι καὶ μικρὸν ἢ ἁπλῶς ἢ ἐκαίνοις εἶναι, εἰ δὲ μή, τοσοῦτόν γε καὶ τοιοῦτον ὥστε μὴ ποιεῖν εὐδαίμονας τοὺς μὴ ὄντας [5] μηδὲ τοὺς ὄντας ἀφαιρεῖσθαι τὸ μακάριον. συμβάλλεσθαι μὲν οὖν τι φαίνονται τοῖς κεκμηκόσιν αἱ εὐπραξίαι τῶν φίλων, ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ αἱ δυσπραξίαι, τοιαῦτα δὲ καὶ τηλικαῦτα ὥστε μήτε τοὺς εὐδαίμονας μὴ εὐδαίμονας ποιεῖν μήτ’ ἄλλο τῶν τοιούτων μηδέν.

[1101a22] But it appears that were the fortunes of one’s descendants and of all one’s friends contribute to no one, this would be very unfriendly and opposite to our opinions (δόξα).

Chapter 12

[1101b10] Διωρισμένων δὲ τοῦτων ἐπισκψώμεθα περὶ τῆς εὐδαιμονίας πότερα τῶν ἐπαινετῶν ἐστὶν ἢ μᾶλλον τῶν τιμίων‧ δῆλον γὰρ ὅτι τῶν γε δυνάμεων οὐκ ἔστιν. φαίνεται δὴ πᾶν τὸ ἐπαινετὸν τῷ ποιόν τι εἶναι καὶ πρός τι πῶς ἔχειν ἐπαινεῖσθαι‧ τὸν γὰρ δίκαιον καὶ τὸν ἀνδρεῖον καὶ ὅλως τὸν [15] ἀγαθόν τε καὶ τὴν ἀρετὴν ἐπαινοῦμεν διὰ τὰς πράξεις καὶ τὰ ἔργα, καὶ τὸν ἰσχυρὸν δὲ καὶ τὸν δρομικὸν καὶ τῶν ἄλλων ἕκαστον τῷ ποιόν τινα πεφυκέναι καὶ ἔχειν πως πρὸς ἀγαθόν τι καὶ σπουδαῖον. δῆλον δὲ τοῦτο καὶ ἐκ τῶν περὶ τοὺς θεοὺς ἐπαίνων‧ γελοῖοι γὰρ φαίνονται πρὸς ἡμᾶς ἀναφερόμενοι, [20] τοῦτο δὲ συμβαίνει διὰ τὸ γίνεσθαι τοὺς ἐπαίνους δι’ ἀναφορᾶς, ὥσπερ εἴπομεν. εἰ δ’ ἐστὶν ὁ ἔπαινος τῶν τοιούτων, δῆλον ὅτι τῶν ἀρίστων οὐκ ἔστιν ἔπαινος, ἀλλὰ μεῖζόν τι καὶ βέλτιον, καθάπερ καὶ φαίνεται‧ τούς τε γὰρ θεοὺς μακαρίζομεν καὶ εὐδαιμονίζομεν καὶ τῶν ἀνδρῶν τοὺς θειοτάτους [25] [μακαρίζομεν]. ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ τῶν ἀγαθῶν‧ οὐδεὶς γὰρ τὴν αὐδαιμονίαν ἐπαινεῖ καθάπερ τὸ δίκαιον, ἀλλ’ ὡς θειότερόν τι καὶ βέλτιον μακαρίζει. δοκεῖ δὲ καὶ Εὔδοξος καλῶς συνηγορῆσαι περὶ τῶν ἀριστείων τῇ ἡδονῇ‧ τὸ γὰρ μὴ ἐπαινεῖσθαι τῶν ἀγαθῶν οὖσαν μηνύειν ᾤετο ὅτι κρεῖττόν ἐστι [30] τῶν ἐπαινετῶν, τοιοῦτον δ’ εἶναι τὸν θεὸν καὶ τἀγαθόν‧ πρὸς ταῦτα γὰρ καὶ τἆλλα ἀναφέρεσθαι. ὁ μὲν γὰρ ἔπαινος τῆς ἀρετῆς‧ πρακτικοὶ γὰρ τῶν καλῶν ἀπὸ ταύτης‧ τὰ δ’ ἐγκώμια τῶν ἔργν ὁμοίως καὶ τῶν σωματικῶν καὶ τῶν ψυχικῶν. ἀλλὰ ταῦτα μὲν ἴσως οἰκειότερον ἐξακριβοῦν [35] τοῖς περὶ τὰ ἐγκώμια πεπονημένοις‧ ἡμῖν δὲ δῆλον ἐκ τῶν [1102a] εἰρημένων ὅτι ἐστὶν ἡ εὐδαιμονία τῶν τιμίων καὶ τελείων. ἔοικε δ’ οὕτως ἔχειν καὶ διὰ τὸ εἶναι ἀρχή‧ ταύτης γὰρ χάριν τὰ λοιπὰ πάντα πάντες πράττομεν, τὴν ἀρχὴν δὲ καὶ τὸ αἴτιον τῶν ἀγαθῶν τίμιόν τι καὶ θεῖον τίθεμεν.

Chapter 13

[1102a5] ‘Επεὶ δ’ ἐστὶν ἡ εὐδαιμονία ψυχῆς ἐνέργειά τις κατ’ ἀρετὴν τελείαν, περὶ ἀρετῆς ἐπισκεπτέον ἂν εἴη‧ τάχα γὰρ οὕτως ἂν βέλτιον καὶ περὶ τῆς εὐδαιμονίας θεωρήσαιμεν. δοκεῖ δὲ καὶ ὁ κατ’ ἀλήθειαν πολιτικὸς περὶ ταύτην μάλιστα πεπονῆσθαι‧ βούλεται γὰρ τοὺς πολίτας ἀγαθοὺς ποιεῖν καὶ τῶν [10] νόμων ὑπηκόους. παράδειγμα δὲ τούτων ἔχομεν τοὺς Κρητῶν καὶ Λακεδαιμονίων νομοθέτας, καὶ εἴ τινες ἕτεροι τοιοῦτοι γεγένηνται. εἰ δὲ τῆς πολιτικῆς ἐστὶν ἡ σκέψις αὕτη, δῆλον ὅτι γίνοιτ’ ἂν ἡ ζήτησις κατὰ τὴν ἐξ ἀρχῆς προαίρεσιν. περὶ ἀρετῆς δὲ ἐπισκεπτέον ἀνθρωπίνης δῆλον ὅτι‧ καὶ γὰρ τἀγαθὸν [15] ἀνθρώπινον ἐξητοῦμεν καὶ τὴν εὐδαιμονίαν ἀνθρωπίνην. ἀρετὴν δὲ λέγομεν ἀνθρωπίνην οὐ τὴν τοῦ σώματος ἀλλὰ τὴν τῆς ψυχῆς‧ καὶ τὴν εὐδαιμονίαν δὲ ψυχῆς ἐνέργειαν λέγομεν. εἰ δὲ ταῦθ’ οὕτως ἔχει, δῆλον ὅτι δεῖ τὸν πολιτικὸν εἰδέναι πως τὰ περὶ ωυχῆς, ὥσπερ καὶ τὸν ὀφθαλμοὺς θεραπεύσοντα [20] καὶ πᾶν {τὸ} σῶμα, καὶ μᾶλλον ὅσῳ τιμιωτέρα καὶ βελτίων ἡ πολιτικὴ τῆς ἰατρικῆς‧ τῶν δ’ ἰατρῶν οἱ χαρίεντες πολλὰ πραγματεύονται περὶ τὴν τοῦ σώματος γνῶσιν. θεωρητέον δὴ καὶ τῷ πολιτικῷ περὶ ωυχῆς, θεωρητέον δὲ τούτων χάριν, καὶ ἐφ’ ὅσον ἱκανῶς ἔχει πρὸς τὰ ζητούμενα‧ [25] τὸ γὰρ ἐπὶ πλεῖον ἐξαδριβοῦν ἐργωδέστερον ἴσως ἐστὶ τῶν προκεμένων. λέγεται δὲ περὶ αὐτῆς καὶ ἐν τοῖς ἐξωτερικοῖς λόγοις ἀρκούντως ἔνια, καὶ χρηστέον αὐτοῖς‧ οἷον τὸ μὲν ἄλογον αὐτῆς εἶναι, τὸ δὲ λόγον ἔχον. ταῦτα δὲ πότερον διώρισται καθάπερ τὰ τοῦ σώματος μόρια καὶ πᾶν τὸ [30] μεριστόν, ἢ τῷ λόγῳ δύο ἐστὶν ἀχώριστα πεφυκότα καθάπερ ἐν τῇ περιφερείᾳ τὸ κυρτὸν καὶ τὸ κοῖλον, οὐθὲν διαφέρει πρὸς τὸ παρόν. τοῦ ἀλόγου δὲ τὸ μὲν ἔοικε κοινῷ καὶ φυτικῷ, λέγω δὲ τὸ αἴτιον τοῦ τρέφεσθαι καὶ αὔξεσθαι‧ τὴν τοιαύτην γὰρ δύναμιν τῆς ψυχῆς ἐν ἅπασι τοῖς τρεφομένοις [1102b] θείη τις ἂν καὶ ἐν τοῖς ἐμβρύοις, τὴν αὐτὴν δὲ ταύτην καὶ ἐν τοῖς τελείοις‧ εὐλογώτερον γὰρ ἢ ἄλλην τινά. ταύτης μὲν οὖν κοινή τις ἀρετὴ καὶ οὐκ ἀνθρωπίνη φαίνεται‧ δοκεῖ γὰρ ἐν τοῖς ὕπνοις ἐνεργεῖν μάλιστα τὸ μόριον τοῦτο καὶ [5] ἡ δύναμις αὕτη, ὁ δ’ ἀγαθὸς καὶ κακὸς ἥκιστα διάδηλοι καθ’ ὕπνον (ὅθεν φασὶν οὐδὲν διαφέρειν τὸ ἥμισυ τοῦ βίου τοὺς εὐδαίμονας τῶν ἀθλίων‧ συμβαίνει δὲ τοῦτο εἰκότως‧ ἀργία γάρ ἐστιν ὁ ὕπνος τῆς ψυχῆς ᾗ λέγεται σπουδαία καὶ φαύλη), πλὴν εἰ μὴ κατὰ μικρὸν καὶ διικνοῦνταί τινες τῶν κινήσεων, [10] καὶ ταύτῃ βελτίω γίνεται τὰ φαντάσματα τῶν ἐπιεικῶν ἢ τῶν τυχόντων. ἀλλὰ περὶ μὲν τούτων ἅλις, καὶ τὸ θρεπτικὸν ἐατέον, ἐπειδὴ τῆς ἀνθρωπικῆς ἀρετῆς ἄμοιρον πέφυκεν. ἔοικε δὲ καὶ ἄλλη τις φύσις τῆς ψυχῆς ἄλογος εἶναι, μετέχουσα μέντοι πῃ λόγου. τοῦ γὰρ ἐγκρατοῦς καὶ ἀκρατοῦς τὸν [15] λόγον καὶ τῆς ψυκῆς τὸ λόγον ἔχον ἀπαινοῦμεν‧ ὀρθῶς γὰρ καὶ ἐπὶ τὰ βέλτιστα παρακαλεῖ‧ φαίνεται δ’ ἐν αὐτοῖς καὶ ἄλλο τι παρὰ τὸν λόγον πεφυκός, ὃ μάχεται καὶ ἀντιτείνει τῷ λόγῳ. ἀτεχνῶς γὰρ καθάπερ τὰ παραλελυμένα τοῦ σώματος μόρια εἰς τὰ δεξιὰ προαιρουμένων κινῆσαι [20] τοὐναντίον εἰς τὰ ἀριστερὰ παραφέρεται, καὶ ἐπὶ τῆς ψυχῆς οὕτως‧ ἐπὶ τἀναντία γὰρ αἱ ὁρμαὶ τῶν ἀκρατῶν. ἀλλ’ ἐν τοῖς σώμασι μὲν ὁρῶμεν τὸ παραφερόμενον, ἐπὶ δὲ τῆς ψυχῆς οὐχ ὁρῶμεν. ἴσως δ’ οὐδὲν ἧττον καὶ ἐν τῇ ψυχῇ νομιστέον εἶναί τι παρὰ τὸν λόγον, ἐναντιούμενον τούτῳ καὶ ἀντιβαῖνον. [25] πῶς δ’ ἕτερον, οὐδὲν διαφέρει. λόγου δὲ καὶ τοῦτο φαίνεται μετέχειν, ὥσπερ εἴπομεν‧ πειθαρχεῖ γοῦν τῷ λόγῳ τὸ τοῦ ἐγκρατοῦς—-ἔτι δ’ ἴσως εὐηκοώτερόν ἐστι τὸ τοῦ σώφρονος καὶ ἀνδρείου‧ πάντα γὰρ ὁμοφωνεῖ τῷ λόγῳ. φαίνεται δὴ καὶ τὸ ἄλογον διττόν. τὸ μὲν γὰρ φυτικὸν οὐδαμῶς κοινωνεῖ [30] λόγου, τὸ δ’ ἐπιθυμητικὸν καὶ ὅλως ὀρεκτικὸν μετέχει πως, ᾗ κατήκοόν ἐστιν αὐτοῦ καὶ πειθαρχικόν‧ οὕτω δὴ καὶ τοῦ πατρὸς καὶ τῶν φίλων φαμὲν ἔχειν λόγον, καὶ οὐχ ὥσπερ τῶν μαθηματικῶν. ὅτι δὲ πείθεταί πως ὑπὸ λόγου τὸ ἄλογον, μηνύει καὶ ἡ νουθέτησις καὶ πᾶσα ἐπιτίμησίς τε [1103a] καὶ παράκλησις. εἰ δὲ χρὴ καὶ τοῦτο φάναι λόγον ἔχειν, διττὸν ἔσται καὶ τὸ λόγον ἔχον, τὸ μὲν κυρίως καὶ ἐν αὑτῷ, τὸ δ’ ὥσπερ τοῦ πατρὸς ἀκουστικόν τι. διορίζεται δὲ καὶ ἡ ἀρετὴ κατὰ τὴν διαφορὰν ταύτην‧ λέγομεν γὰρ αὐτῶν τὰς [5] μὲν διανοητικὰς τὰς δὲ ἠθικάς, σοφίαν μὲν καὶ σύνεσιν καὶ φρόνησιν διανοητικάς, ἐλευθεριότητα δὲ καὶ σωφροσύνην ἠθικάς. λέγοντες γὰρ περὶ τοῦ ἤθους οὐ λέγομεν ὅτι σοφὸς ἢ συνετὸς ἀλλ’ ὅτι πρᾶος ἢ σώφρων‧ ἐπαινοῦμεν δὲ καὶ τὸν σοφὸν κατὰ τὴν ἕξιν‧ τῶν ἕξεων δὲ τὰς ἐπαινετὰς ἀρετὰς λέγομεν.

.

1102a7-12:

And it seems that the true politician has toiled away at this [i.e. virtue] most of all, for they want to make their citizens good and obedient to the laws. And as an example of this we have the Cretan and Lacedemonian [i.e. Spartan] legislators, and any others of the sort that has come into being.

Bibliography

the Greek: Aristoteles. Aristotelis Ethica Nicomachea. Edited by I. Bywater, E Typographeo Clarendoniano, 1986.

with reference to the following English translations:

Aristotle, and Terence Irwin. Nicomachean Ethics. Second ed., Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1999.

Aristotle, and Roger Crisp. Nicomachean Ethics. Cambridge University Press., 2000.