I run an Instagram account @AristotleWalks to share Aristotle’s work. I hope you like it!

The paraphrase in the photos may to some seem oversimplified. This is intentional and done for the sake of making the text palatable for those who have never read Aristotle carefully.

The original Greek text and my English translation are in the captions. The texts I have translated for this project without the photos can be found here. Every background photo is shot by me.

Do you wait to be called?

About the Text: This comes near the end of the two books [book Θ (theta) & Ι (iota)] in the Nicomachean Ethics devoted to φιλία (philia), which is usually translated in English to ‘friendship’. φιλία isn’t quite ‘friendship’, though. The Greek term, which you recognize in *philo*sophy (‘love’ of ‘sophia’, sophia is ‘wisdom’ in Greek), hydro*phile* (hydro = water, a molecule attracted to water)… is more general than the English ‘friendship’. φιλία, in this Nicomachean Ethics context, encompasses a wider range of relationships than what you (as an English speaker; but also I can speak to 友達, 朋友, ein Freund, y un amigo) probably think of when you think of someone you would call a ‘friend’. Family members are also included in the Ancient Greek as an object of φιλία… I’ll share more on what Aristotle thinks of φιλία in the future! ***Which languages do you speak? How does ‘friendship’ in your language work?**

[Right before this passage Aristotle discusses how when we are in fortunate circumstances we should eagerly invite our friends to share in our good fortune, but we must hesitate to share with them our bad fortune.]

Nicomachean Ethics I.11 1171b20-23:

ἰέναι δ’ ἀνάπαλιν ἴσως ἁρμόζει πρὸς μὲν τοὺς ἀτυχοῦντας ἄκλητον καὶ προθύμως (φίλου γὰρ εὖ ποιεῖν, καὶ μάλιστα τοὺς ἐν χρείᾳ καὶ [τὸ] μὴ ἀξιώσαντας· ἀμφοῖν γὰρ κάλλιον καὶ ἥδιον)

“And inversely, it is fitting to go towards friends in misfortune without being called and eagerly, for it does well of a friend [to do so], and most of all to those in need and did not think themselves worthy of it, for to both this is more fine and pleasant.”

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako on the water taxi on Hydra Island; it’s actually continuous from the photo in the post right below 😉.

What do you think of what he says a few lines afterwards: ‘whenever you want to suggest someone to do something, think of what you want to praise of them; whenever you want to praise someone, think of what you want them to do’?

About the Text: Aristotle thinks that a speech to praise someone, reformulated linguistically, can always be turned into a piece of advice (to continue to act in one way or another, to encourage certain behavior). I think this is great insight Aristotle offers that could be helpful in figuring out how to formulate what one says to others 🙂

Rhetoric I.9.35-36 1367b36-68a5:

ἔχει δὲ κοινὸν εἶδος ὁ ἔπαινος καὶ αἱ συμβουλαί. ἅ γὰρ ἐν τῷ συμβουλεύειν ὑπόθοιο ἄν, ταῦτα μετατεθέντα τῇ λέξει ἐγκώμια γιγνεται. ἐπεὶ οὖν ἔχομεν ἅ δεῖ πράττειν καὶ ποῖόν τινα εἶναι δεῖ, ταῦτα ὡς ὑποθήκας λέγοντας τῇ λέξει μετατιθέναι δεῖ καὶ στρέφειν, οἷον ὅτι οὐ δεῖ μέγα φρονεῖν ἐπὶ τοῖς διὰ τύχην ἀλλὰ τοῖς δι’ αὑτόν. οὕτω μὲν οὖν λεχθὲν ὑποθήκην δύναται, ὡδὶ δ’ ἔπαινον μέγα φρονῶν οὐκ ἐπὶ τοῖς διὰ τύχην ὑπάρχουσιν ἀλλὰ τοῖς δι’ αὑτόν. ὥστε ὅταν ἐπαινεῖν βούλῃ, ὅρα τί ἂν ὑπόθοιο: καὶ ὅταν ὑποθέσθαι, ὅρα τί ἂν ἐπαινέσειας.

“Praise and advices have a common feature, for that which you would suggest in giving advice becomes an encomium [i.e. a speech of praise, e.g. the Encomium of Helen by Gorgias] if they are expressed differently. Thus since we grasp that which must be done and what qualities [as people] we must have, we must express these things differently and turn them…. Thus, whenever you want to praise someone, look at what you would suggest; whenever you want to suggest something, look at what you would praise.”

[1. I did not finalize my translation of his example in the ellipses, but in it, Aristotle says that people should not feel pride from things they have that is due to luck rather than their own actions, their own merit.

2. συμβουλή, which means advice/council, here in the Rhetoric has the sense of political council one gives to government officials to take action in one way or another, which is why in the photo I translated it as ‘to urge someone to do something’. 😊

3. an ‘encomium’ is a speech of praise, e.g. the Encomium of Helen by Gorgias… which is AMAZING! 😊]

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Freese (1924) and Roberts (1924), as well as Cope (1877).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako Tsigrado Beach, Milos, Cyclades, Greece. I LOVE Milos. Wish I could go back, sigh.

Easy enough. No, I’m kidding haha 😊 Read the full passage [below] or my About the Text in the comments section for why this is the case 😉

About the Text: I love how the Rhetoric gives you tons of helpful advice on how to *seem* good haha… but Aristotle is very on point. Here he basically says, ‘if people see multiple pieces of evidence that suggest you’re a good person, then they will believe it [even if some of the actions that make up their ‘evidence’ were due to chance/accidental]’. There are two thoughts about human nature that I care to mention today! (1) Human beings love to—or at least naturally—find patterns even when there aren’t any, sure, and (2) Human beings seem to psychologically accept beliefs *without* sufficient evidence, so long as it seems plausible / the belief has enough explanatory force to explain phenomena. I wonder how many false beliefs I have accumulated due to this phenomenon? 😊

Rhetoric I.9 1367b22-27:

“Since praise is based on actions, and it is characteristic of excellent actions to have been done on the basis of choice, we must try to show when a person acts on the basis of choice; and it is useful if a person appears to have done [excellent actions] often, and because of this one must take accidents and things from luck as based on choices, for if many similar [excellent actions] are brought forward, it seems to be a sign of virtue and choice.”

ἐπεὶ δ’ ἐκ τῶν πράξεων ὁ ἔπαινος, ἴδιον δὲ τοῦ σπουδαίου τὸ κατὰ προαίρεσιν, πειρατέον δεικνύναι πράττοντα κατὰ προαίρεσιν. χρήσιμον δὲ τὸ πολλάκις φαίνεσθαι πεπραχότα. διὸ καὶ τὰ συμπτώματα καὶ τὰ ἀπὸ τύχης ὡς ἐν προαιρέσει ληπτέον· ἂν γὰρ πολλὰ καὶ ὅμοια προφέρηται, σημεῖον ἀρετῆς εἶναι δόξει καὶ προαιρέσεως.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Freese (1924) and Roberts (1924), as well as Cope (1877).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako of the water during a taxi ride (yeah it’s a taxi-boat) from one part of Hydra Island to another, Greece, not that you can tell nor that it’s important lol.

He has a ‘not great’ opinion of these people, naturally. In Ancient Greek if the text says ‘this makes a not small difference’, it means, ‘this makes a HUGE difference’! haha 🙂

About the Text: Though Aristotle had a very poor opinion of sophists, he basically wrote a manual for them anyway. In his work the Sophistic Refutations, Aristotle explains the many different kinds of fallacies there are which sophists use; the two overarching categories for them are (1) fallacies in the language and (2) fallacies not in the language. Please make sure I never present any haha 😊 Oh, don’t worry I will present his types of fallacies, I mean, please catch me if I spit trash out from my mouth.

Sophistical Refutations I.1 165a20-25:

“And then for some it is more profitable to seem to be wise than to be wise without seeming to be so (for sophistry is seeming wise without being so, and the sophist makes money from seeming wise rather than being so). It is clear that for them it is necessary to seem to do work of the wise person more than to actually do it without seeming to.”

ἐπεὶ δ’ ἐστί τισι μᾶλλον πρὸ ἔργου τὸ δοκεῖν εἶναι σοφοῖς ἢ τὸ εἶναι καὶ μὴ δοκεῖν (ἔστι γὰρ ἡ σοφιστικὴ φαινομένη σοφία οὖσα δ’ οὔ, καὶ ὁ σοφιστὴς χρηματιστὴς ἀπὸ φαινομένης σοφίας ἀλλ’ οὐκ οὔσης), δῆλον ὅτι ἀναγκαῖον τούτοις καὶ τὸ τοῦ σοφοῦ ἔργον δοκεῖν ποιεῖν μᾶλλον ἢ ποιεῖν καὶ μὴ δοκεῖν.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Pickard-Cambridge (1928) and Forster (1955?).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako at Cabo da Roca, the westernmost part of continental Europe, Portugal.

Did you know that the word ‘lesbian’ comes from ‘Lesbos’ (the Greek island!) because Sappho (7th–6th century BC, one of the most famous lyric poets of antiquity) wrote love poems to women, and she was from there? In this poem she turns away a man. I kid you not. On another note, as of today it has been 1.5 months since I started this account 😊

About the Text: I will not be sharing any amateur poetry interpretations nor will I be posting any poems for some time [see caption]. What is crucial to Aristotle’s philosophy is that Sappho is said to have said these brutally honest (‘be better’) lines in response to Alcaeus (a bro) who basically said ‘I can’t tell you about the dirty things I want to do to you’. No it’s not so crucial to Aristotle’s philosophy, but I love it.

Aristotle quotes Sappho’s lyric poem at Rhetoric I.9 1367a11-14:

After toiling away for 3 hours trying and failing to translate this into a pleasant English poem, I present you Roberts’ (1924) pretty and rhyming translation:

“If for things good and noble thou wert yearning,

If to speak baseness were thy tongue not burning,

No load of shame would on thine eyelids weigh;

What thou with honour wishest thou wouldst say.”

Translating poetry is not my calling. Here is a more literal translation:

“If you had desired good or noble things,

and if your tongue were not stirring up some evil,

shame would not have filled up your eyes,

but rather you would have spoken justly.”

αἰ δ’ εἶχες ἐσθλῶν ἵμερον ἢ καλῶν

καὶ μη τι Fειπῆν γλῶσσ’ ἐκύκα κακόν,

αἰδώς κέ σ’ οὐκ ἂν εἶχεν ὄμματ’,

ἀλλ’ ἔλεγες περὶ τῶ δικαίω.

The first translation is by Roberts (1924); the second is by @masako.toyoda with guidance from Prentice (1918), Freese (1924), Roberts (1924), and Cope (1877).

Background photo shot of birds in the sky by @happinesium.masako between the Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque, Istanbul, Turkey; I thought it fitting because Lesbos, though Greek, is closer to mainland Turkey than mainland Greece. Please don’t tell my Greek friends @leah.fuku I said that. These things should never be mentioned.

Thought the lights vaguely resembled neurons…! what a nerd. This passage (below) is one of my *favorite* parts of Aristotle’s theory of action; it gets me MOVING.

About the Text: If you read the full passage in the caption, you might be confused regarding the terminology for the efficient and final causes. Aristotle’s theory of causes is so central and important to the rest of his philosophy—I will do a video on the basics of Aristotle’s Four Causes soon 😊 For today, let us set that aside.

Here Aristotle discusses the necessity for *both* thought (i.e. exercise of our capacity to reason by way of deliberation) and a desire (which is necessarily for some goal, i.e. τέλος). The term for desire, ὄρεξις, is a term that encompasses many things (lust, ‘I want that cake’, ‘I want to help my friend’), but in any case, it has motivational power for a person to act! Essentially, this motivational force AND reason must come together for someone to consciously act well or badly. Aristotle thinks that to become a good person and thus to become happy, you need to develop both your intellect and your desires to orient towards what is right, what is good. I loveee this part of Aristotle’s ethics, and with future posts I hope to share more of it with you! 😊

Nicomachean Ethics Z2 1139a31-36:

“The starting point of an action—the efficient cause, not the final cause—is decision; and [the starting point] of a decision is a desire and goal-directed reasoning. This is why a decision cannot exist [i.e. be made] without intellect and thought nor without a state of character, for acting well and its opposite cannot exist [does not occur] without thought and character. And thought by itself moves nothing; but rather, goal-directed and activity-oriented thought [moves us]…”

πράξεως μὲν οὖν ἀρχὴ προαίρεσις—ὅθεν ἡ κίνησις ἀλλ’ οὐχ οὗ ἕνεκα—προαιρέσεως δὲ ὄρεξις καὶ λόγος ὁ ἕνεκά τινος. διὸ οὔτ’ ἄνευ νοῦ καὶ διανοίας οὔτ’ ἄνευ ἠθικῆς ἐστὶν ἕξεως ἡ προαίρεσις· εὐπραξία γὰρ καὶ τὸ ἐναντίον ἐν πράξει ἄνευ διανοίας καὶ ἤθους οὐκ ἔστιν. διάνοια δ’ αὐτὴ οὐθεν κινεῖ, ἀλλ’ ἡ ἕνεκά του καὶ πρακτική·

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako auf dem Weihnachtsmarkt am Marienplatz, München, Deutschland // in the Marienplatz Christmas market, Munich, Germany.

Well I guess we don’t have any [true politicians]! (puzzled? I explain the background basics of what Aristotle thinks a true politician is in the About the Text in the comments! 😊)

About the Text: Aristotle, similar to Plato, has an interesting conception of what it means to be a true politician, a true craftsman, any given ‘true’ version of profession X. Let’s take up the dearly-loved-example of the doctor. A ‘true doctor’, insofar as they are a doctor, ‘heals human bodies for the sake of their patient’. Yes, there are doctors in real life who heal patients to earn money or even engage in medical malpractice and abuse their patients. But as much as that doctor does these things, they *deviate* from being a true doctor. Similarly, the ‘true politician’ for Aristotle ‘governs well for the sake of their subjects’. A money-hungry, backstabbing, bribe-receiving, self-interested politician deviates from their true calling.

Nicomachean Ethics A13 1102a7-12:

“And it seems that the true politician has toiled away at this [i.e. virtue] most of all, for they want to make their citizens good and obedient to the laws. And as an example of this we have the Cretan and Lacedemonian [i.e. Spartan] legislators, and any others of the sort that has come into being.”

δοκεῖ δὲ καὶ ὁ κατ’ ἀλήθειαν πολιτικὸς περὶ ταύτην μάλιστα πεπονῆσθαι‧ βούλεται γὰρ τοὺς πολίτας ἀγαθοὺς ποιεῖν καὶ τῶν νόμων ὑπηκόους. παράδειγμα δὲ τούτων ἔχομεν τοὺς Κρητῶν καὶ Λακεδαιμονίων νομοθέτας, καὶ εἴ τινες ἕτεροι τοιοῦτοι γεγένηνται.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako in the Stoa of Attalos in the Ancient Agora of Athens, Athens, Greece.

If you look closely, Aristotle is walking. Oh, no, not in the photo, that’s not Aristotle, that’s my friend. I meant in life.

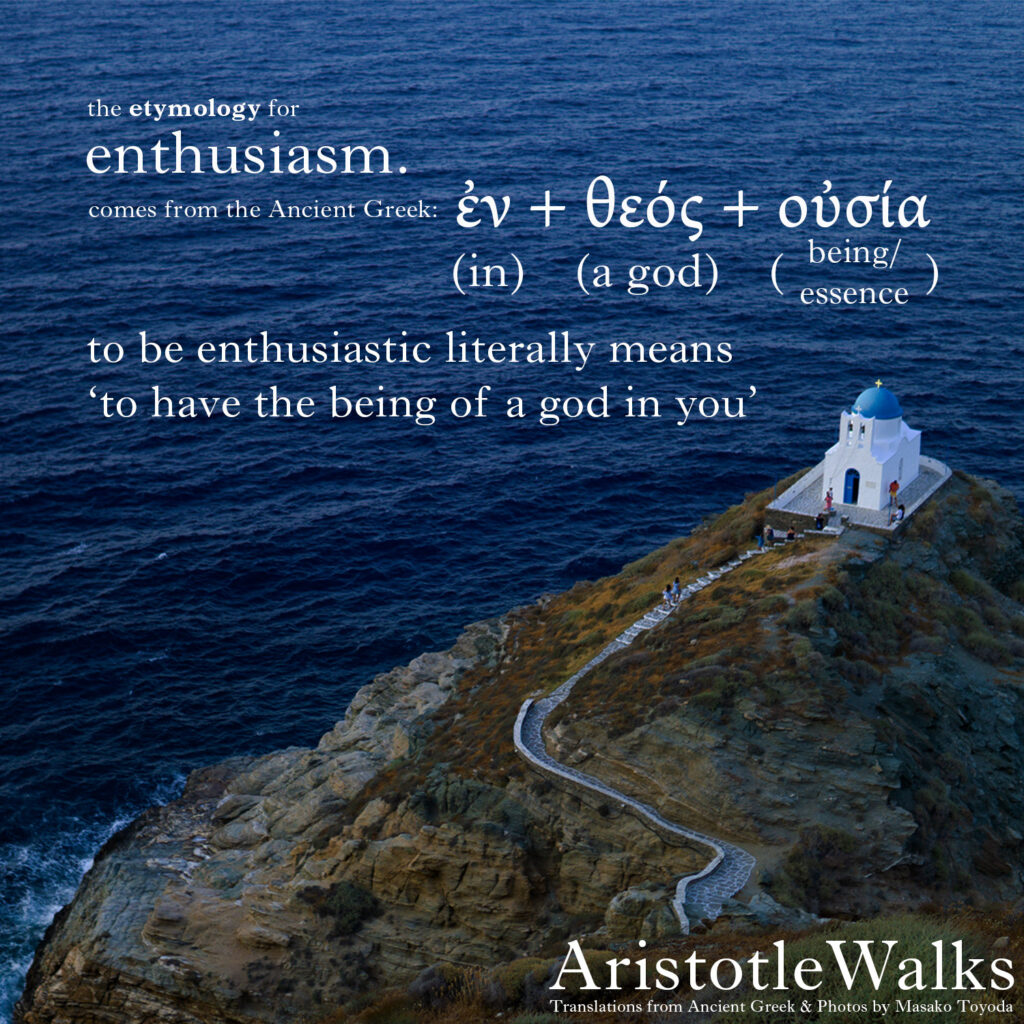

About the Text: I could say many complicated things about today’s text, but instead I would like to take the time to discuss εὐδαιμονία—translated to ‘happiness’. There are many reasons why the English ‘happiness’ is a bad translation for εὐδαιμονία. ‘happiness’ is often conceptualized as a fleeting feeling of joy, but to say that of εὐδαιμονία would be OUTRAGEOUS indeed. εὐδαιμονία is a sort of lifelong, true, full, complete, stable sort of flourishing or prospering. To enjoy a eudaimonious life is to live a blessed and—at least in Aristotle’s case—virtuous life. εὐδαιμονία breaks down as a word intο εὖ (‘well’, adverb of ‘good’) and δαίμων (a protective spirit/deity/god); to have εὐδαιμονία is to have a god watching over you well!

More About the Text: Just realized I should add that Aristotle thinks that taking various good actions and to do so repeatedly creates a good person and, of courseeee, being virtuous is intrinsically joyful and εὐδαιμονία-inducing! The ‘of courseeee’ in the previous sentence is sass, yes, because this is far from obvious and is something for which Aristotle spends basically the entire rest of the Nicomachean Ethics arguing! 🙂

Nicomachean Ethics A10 1099b20-25:

“And if it is better to attain εὐδαιμονία thus [through some sort of learning or cultivation of virtue] than through fortune, then it is reasonable for it to be this way since things according to nature are naturally in the finest possible condition and thus similarly this is also the case for things according to craft and all cause (αἰτία), and especially for things according to the best cause; and it would be seriously outrageous to entrust what is great and finest to fortune.”

The content in the [] is pulled from 1099b15-16 and 19-20, I did not conjure it with fortune 😊

εἰ δ’ ἐστὶν οὕτω βέλτιον ἢ τὸ διὰ τύχην εὐδαιμονεῖν, εὔλογον ἔχειν οὕτως, εἴπερ τὰ κατὰ φύσιν, ὡς οἷόν τε κάλλιστα ἔχειν, οὕτω πέφυκεν, ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ τὰ κατὰ τέχνην καὶ πᾶσαν αἰτίαν, καὶ μάλιστα {τὰ} κατὰ τὴν ἀρίστην. τὸ δὲ μέγιστον καὶ κάλλιστον ἐπιτρέψαι τύχῃ λίαν πλημμελὲς ἂν εἴη.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako while hiking in the Austrian Alps, Tirol, Austria.

If you walk from the Akropolis Museum towards Syntagma Square, you will find this statue of Alexander the Great, student to Aristotle the Way More Excellent between the years 343-340 BC. Is this really an Aristotle page? Or a Greek tourism page? 😉 It’s an Aristotle page, body and soul.

About the Text: Why does it have to be so hard? Well as you may have already heard, Aristotle thinks that figuring what the right thing to do is a matter of finding the perfect mean (not numerically or anything misguided like that) between two extremes (Doctrine of the Mean). For example, do not get too angry, but it’s also bad to be not angry enough. The mechanism behind the Doctrine of the Mean is very complex and *so* important to Aristotle’s ethical theory that I think I have to do a video in the future, but for today… basically there are many ways an action can go wrong and hitting that mean (τὸ μέσον) is veryyy difficult. #goals

Nicomachean Ethics B9 1109a24-30:

“Wherefore it is also hard work to be excellent, for in each case it takes hard work to find the mean. For example, not everyone, but only the person who knows how finds the midpoint of a circle. And thus also it is easy for anyone to get angry or to give and spend money, but to do so to the right person, to the right extent, at the right time, for the right aim, and in the right way is not still for everyone, nor still easy. Thus, doing something well is rare, praiseworthy, and noble.”

διὸ καὶ ἔργον ἐστὶ σπουδαῖον εἶναι. ἐν ἑκάστῳ γὰρ τὸ μέσον λαβεῖν ἔργον, οἷον κύκλου τὸ μέσον οὐ παντὸς ἀλλὰ τοῦ εἰδότος· οὕτω δὲ καὶ τὸ μὲν ὀργισθῆναι παντὸς καὶ ῥᾴδιον, καὶ τὸ δοῦναι ἀργύριον καὶ δαπανῆσαι· τὸ δ’ ᾧ καὶ ὅσον καὶ ὅτε καὶ οὗ ἕνεκα καὶ ὥς, οὐκέτι παντὸς οὐδὲ ῥᾴδιον· διόπερ τὸ εὖ καὶ σπάνιον καὶ ἐπαινετὸν καὶ καλόν.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako in Athens, Greece.

Before there was ‘weakness of will’, there was akrasia… and (as always,) Aristotle!

About the Text: Why is it so difficult to judge what one ought to do? Aristotle thinks that one reason for this is that there are so many particular details to a circumstance that are relevant to determine if one should do X or not do X… that it is hard to get them all straight and see how they add up. More on this in the future.

Another major reason for this is one that also contributes to the difficulty to abide by one’s judgment. What one perceives as pleasurable/painful is a direct product of one’s non-rational part of the soul (a part of the soul that must be trained by the rational part to learn what is good as pleasurable and what is bad as painful—i.e. find virtuous things appealing and find vicious things appalling). Since the non-rational part of the soul produces many desires that are directed towards vicious/base/bad things, an agent is often pulled in the direction of rationalizing that something bad is what they ought to do, or if in the case they successfully assess what they ought to do, then they are often pulled in the direction of not doing what they know they ought to do (akrasia, modern: ‘weakness of will’). More on this in the future! I love Aristotle.

There are other reasons for why it is so difficult to judge what one ought to do, but that we can discuss in the future! with my favorite book of the Nicomachean Ethics, Zeta (VI in Bywater). 😊

Nicomachean Ethics Γ1 1110a29-34:

“And it is sometimes difficult, however, to judge what [good] sort of thing should be chosen at the price of what [bad] sort of thing, and what should be endured as the price of what. It is still more difficult to abide by our judgment, for the expected outcomes are for the most part painful, and the actions we are compelled [to endure] are for the most part shameful.”

ἔστι δὲ χαλεπὸν ἐνίοτε διακρῖναι ποῖον ἀντὶ ποίου αἱρετέον καὶ τί ἀντὶ τίνος ὑπομενετέον, ἔτι δὲ χαλεπώτερον ἐμμεῖναι τοῖς γνωσθεῖσιν‧ ὡς γὰρ ἐπὶ τὸ πολύ ἐστι τὰ μὲν προσδοκώμενα λυπηρά, ἃ δ’ ἀναγκάζονται αἰσχρά‧ Bywater OCT.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako I think in Porto Cheli, Peninsula of Argolida by the Argolic Gulf, Greece.

…so if you experience schadenfreude* what does that say about you?

*schadenfreude is a German term for the pleasure one feels when they see others suffer.

About the Text: Today’s text is pulled from a very controversial part of Aristotle’s ethical theory! EN Γ1-7 discusses moral agency. Basically, Aristotle argues for the claim that human beings are responsible for having acquired virtues and vices, good and bad states of character.

.

Since one would have to be a complete idiot not to know that doing an action of type X (e.g. selfish, lazy) results in them becoming a type X person (e.g. egoist, procrastinator), the outcome that one is good or bad is a result of that person repeatedly deciding to do good or bad actions. Since one is responsible for the actions one took that led them to their state of character, one is responsible for one’s state of character.

.

Further, since one’s state of character determines the appeal that good and bad actions have (e.g. being mean is appealing to a mean person, bullying is appealing to a bully, being kind is appealing to a kind person), and one is responsible for one’s state of character, one is responsible for the way things appear.

.

I’m presenting Aristotle’s thoughts in **very** broad strokes. If you would like to understand more, I would recommend Susan Sauvé Meyer’s book: Aristotle on Moral Agency (2011)! 😊 I will also discuss more of these chapters in the future, of course—I loveee these chapters (I’ve actually given lectures on these chapters)!

Nicomachean Ethics Γ7 1114a31-b3:

“Now someone might say that everyone aims at the apparent good, but how it appears is not in their power, but on the contrary, how the end appears to each person depends on their state of character. Thus, if each person is in some way responsible for their own state of character, they are also in some way responsible for how the end appears.”

εἰ δε τις λέγοι ὅτι πάντες ἐφίενται τοῦ φαινομένου ἀγαθοῦ, τῆς δὲ φαντασίας οὐ κύριοι, ἀλλ’ ὁποῖός ποθ’ ἕκαστός ἐστι, τοιοῦτο καὶ τὸ τέλος φαίνεται αὐτῷ‧ εἰ μὲν οὖν ἕκαστος ἑαυτῷ τῆς ἕξεώς ἐστί πως αἴτιος, καὶ τῆς φαντασίας ἔσται πως αὐτὸς αἴτιος‧

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @masako.toyoda in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Side personal note: I suppose schadenfreude is exactly the phenomenon that has driven humans to perpetuate hurt-inducing behavior ☹ I suppose when spreading hate appears appealing/fun and one even convinces oneself that it is in fact good or right, then it would of course be hard to stop oneself from doing it. May the world become a better place and individuals cease to hurt others and themselves.

p.s. he thinks most people are like this 😉 what does that mean… for you?

About the Text: In the first several chapters of the third book (Γ) of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle discusses moral agency, the criteria by which certain actions are considered voluntary (hekon) or involuntary (akon), the criteria by which certain actions are praised or blamed, etc. These sections ultimately culminate to a controvertial conclusion at 1114b22-25: virtues and thus also vices are voluntarily acquired–we are morally responsible for our state of character and actions we decide to take through our state of character.

Today’s passage highlights one of the ways an action can be involuntary, namely, when one takes an action with a very particular kind of ignorance: the ignorance of critical details of the circumstances within which the action is taken. For example (1111a15ish), someone might give a friend a drink thinking that it is water, but the drink is actually poison, killing the friend. This action is done involuntarily, though it still warrants pain and regret in the agent.

Nicomachean Ethics Γ2 1110b28-1111a2:

“Every vicious person, then, is ignorant of what they must do or must abstain from. This kind of mistake makes people unjust, and generally bad. But when someone is ignorant of what things are good for them it is not called ‘involuntary’, because the cause of involuntary action is not ignorance in the decision—which leads to vice, nor because of ignorance of the universal [proposition of something being good or bad]—for that one is blamed, but ignorance of the particulars, in within which the action consists and with which it is concerned, for it is on these [particulars] that both pity and pardon depend.”

ἀγνοεῖ μὲν οὖν πᾶς ὁ μοχθηρὸς ἃ δεῖ πράττειν καὶ ὧν ἀφεκτέον, καὶ διὰ τὴν τοιαύτην ἁμαρτίαν ἄδικοι καὶ ὅλως κακοὶ γίνονται‧ τὸ δ’ ἀκούσιον βούλεται λέγεσθαι οὐκ εἴ τις ἀγνοεῖ τὰ συμφέροντα‧ οὐ γὰρ ἡ ἐν τῇ προαιρέσει ἄγνοια αἰτία τοῦ ἀκουσίου ἀλλὰ τῆς μοχθηρίας, οὐδ’ ἡ καθόλου (ψέγονται γὰρ διά γε ταύτην) ἀλλ’ ἡ καθ’ ἕκαστα, ἐν οἶς καὶ περὶ ἃ ἡ πρᾶξις‧ ἐν τούτοις γὰρ καὶ ἔλεος καὶ συγγνώμη‧

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako in the Alps, Tirol, Austria.

What subject are you working on?

About the Text: This is early in the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle’s famous work on how one ought to live one’s life. In this particular passage, Aristotle is concerned with the methodology appropriate for ethics (political science, he calls it). Different fields of study call for varying degrees of exactness in their arguments. Ethics, it turns out for Aristotle, does not require airtight [as in universally true] premises with [logically] airtight arguments—it is not appropriate to the field of ethics to call for premises that hold more than ‘for the most part’. Thus also the arguments will not be–in fact should not be–airtight, neither.

Nicomachean Ethics A3 1194b22-27:

“It is also necessary to in the same way demonstrate each thing we discuss; for the educated person seeks out precision according to each kind, until so much, up to as much, admitted by the nature of the subject, for it appears similarly [absurd] to accept a mathematician arguing from probability as to ask a rhetorician for a proof.”

τὸν αὐτὸν δὴ τρόπον καὶ ἀποδέχεσθαι χρεὼν ἕκαστα τῶν λεγομένων‧ πεπαιδευμένου γάρ ἐστιν ἐπὶ τοσοῦτον τἀκριβὲς ἐπιζητεῖν καθ’ ἕκαστον γένος, ἐφ’ ὅσον ἡ τοῦ πράγματος φύσις ἐπιδέχεται‧ παραπλήσιον γὰρ φαίνεται μαθηματικοῦ τε πιθανολογοῦντος ἀποδέχεσθαι καὶ ῥητορικὸν ἀποδείξεις ἀπαιτεῖν.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako on Hydra Island, Greece.

So many cats in Athens have so much imagination. 😉

About the Text: In De Anima, Aristotle seeks to figure out the nature, essence and properties of ‘soul’. One thing that is incredible! about this text is that Aristotle’s discussion of ‘soul’ involves not only human soul, but all souls, including plants and other animals, a feature not found much (if at all) among thinkers who came before him. Today’s passage is pulled from the last few chapters of Aristotle’s treatise, and thus it is a conclusion he draws after a great deal of build up. ‘imagination’ in the English does not capture well ‘φαντασία’ (pronounced: phantasia) in the Ancient Greek original. It is I think more accurate to describe φαντασία as something like ‘the capacity by which an organism with consciousness grasps an appearance/representation of something’. From previously in De Anima, Aristotle concludes in our text today: (rational or sensory) imagination [/φαντασία] -> appetite/desire [/ὄρεξις] -> self-directed movement. 🙂

De Anima III.10 433b-19:

“In sum, as has been said, it is insofar as an animal is capable of appetite/desire (ὄρεξις) that it is capable of moving itself; but it is not capable of desire without imagination (φαντασία). And all imagination is either rational or perceptual/sensory. And in the latter, the other [non-human] animals have a share as well.”

ὅλως μὲν οὖν, ὥσπερ εἴρηται, ᾗ ὀρεκτικὸν τὸ ζῷον, ταύτῃ αὑτοῦ κινητικόν· ὀρεκτικὸν δὲ οὐκ ἄνευ φαντασίας· φαντασία δὲ πᾶσα ἢ λογιστικὴ ἢ αἰσθητική. ταύτης μὲν οὖν καὶ τὰ ἄλλα ζῷα μετέχει.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Smith (1931) & Shields (2016).

Photo shot by @happinesium.masako of a street cat in Athens, Greece.

‘equality’ vs. ‘equity’ by Aristotle, two millennia+ before anyone started creating memes and Instagram infographics on this topic.

About the Text: I wanted to share this because I find it funny how many people think that they have thought up new ideas in the past few thousand years… when in reality, whatever we might be thinking about today, Aristotle probably already thought about it haha 😊 The idea in the photo above is a real part of Aristotle’s work, of course [see below], but basically it’s a harm version of all the memes you have probably seen lately about the difference between ‘equality’ and ‘equity’ for opportunities.

Today’s passage is from the same section as yesterday’s; Aristotle discusses the indicators for what is better or worse, indicators that hold ‘for the most part’. Things that are rarer and more beloved are better than what is not—the ‘better’ here is I think best interpreted as evoking a sense of preference, i.e. X is preferred more than Y.

Rhetoric I.7.41 1365b16-19:

“…and that which is beloved [is better than what is not]—the sort which some have just one, others have more. Wherefore the penalty were someone to blind a one-eyed person is not equal to the penalty were someone to half-blind a person with two eyes, for the one-eyed person has had that which is beloved taken from them.”

καὶ τὸ ἀγαπητόν, καὶ τοῖς μὲν μόνον τοῖς δὲ μετ’ ἄλλων. διὸ καὶ οὐκ ἴση ζημία, ἄν τις τὸν ἑτερόφθαλμον τυφλώσῃ καὶ τὸν δύ’ ἔχοντα‧ ἀγαπητὸν γὰρ ἀφῄρηται.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Freese (1924) and Roberts (1924), as well as Cope (1877).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako in the woods at Obersalzberg (the site of a Dokumentationszentrum for Hitler’s mountain retreat), above Berchtesgaden, Bavaria, Germany.

What do you choose when no one’s watching?

About the Text: Today’s passage is from the same section as yesterday’s, where Aristotle discusses the indicators for what is generally better or worse. Today we have an indicator to which Aristotle is strongly committed: things that are directed towards truth, reality are better than… basically, anything else! Cope, Freese, and Roberts all agree that the ἀλήθεια vs. δόξα dichotomy in the text is that of ‘what it is’ vs. ‘what it seems’, i.e. the substance vs. appearance/reputation of a person, and I agree. Cope sums it up quite nicely in his commentary I think: “the virtuous man ‘will be virtuous in solitudine, and not only in theatro’…. It is the credit of possessing the thing, in the eyes of the others, and not the mere possession for its own sake, that gives it its value and superiority” for the things that are πρὸς δόξαν. These things which aim at appearances do not provide value independently, and thus they are worse than things that aim at reality which do.

Please let me know if you would like for me to avoid Latin and/or Greek in my ‘About the Text’ sections! 😊

Rhetoric I.7.36 1365a35-b4:

“And the things that aim at reality are better than those that aim at appearances. The ‘definition’ of that which aims at appearances consists in that which one would not choose were they likely to escape others’ notice. Through this it would seem to be the case that to be acted upon well (i.e. to receive benefits) is chosen more than to do upon others well (i.e. to give benefits), for to receive benefits is chosen even if no one were watching, but to do upon others well does not seem to be chosen if now one were watching.”

καὶ τὰ πρὸς ἀλήθειαν τῶν πρὸς δόξαν. ὅρος δὲ τοῦ πρὸς δόξαν, ὃ λανθάνειν μέλλων οὐκ ἂν ἕλοιτο. διὸ καὶ τὸ εὖ πάσχειν τοῦ εὖ ποιεῖν δόξειεν ἂν αἱρετώτερον εἶναι‧ τὸ μὲν γὰρ κἂν λανθάνῃ αἱρήσεται, ποιεῖν δ’ εὖ λανθάνων οὐ δοκεῖ ἂν ἑλέσθαι.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Freese (1924) and Roberts (1924), as well as Cope (1877).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako on Hydra Island, Greece.

just saying

About the Text: hahaha… so! the context of this passage… Aristotle is in the midst of a very long discussion about the various different criteria or indications for what is good and bad, or at least what is better and worse than another. Recall that Aristotle thinks these sorts of generalizations “only hold for the most part”; Aristotle is giving general guidelines that are good heuristics for what has more or less value than another. In this particular passage, we have a rather Platonic indicator—Plato thought that the Form of the Good has to be eternal, because the best things are perfect and thus would never destruct. Similarly, Aristotle seems to be saying that good things tend to last longer than worse things. Given its location in the Rhetoric, Aristotle is probably thinking of political regimes that last longer are better, i.e. the fact that a given constitution can stay intact for longer suggests that that constitution was better formulated.

But taken out of context it just sounds like….

Rhetoric I.7.26 1364b30:

“And the things that last longer are better than those which are more fleeting, and the things that are more secure are better than those which are less so, for the use prevails when something lasts longer in time and when more secure in fulfilling our wishes.”

καὶ τὰ πολυχρονιώτερα τῶν ὀλιγοχρονιωτέρων καὶ τὰ βεβαιότερα τῶν μὴ βεβαιοτέρων‧ ὑπερέχει γὰρ ἡ χρῆσις τῶν μὲν τῷ χρόνῳ τῶν δὲ τῇ βουλήσει‧

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Freese (1924) and Roberts (1924), as well as Cope (1877).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako in Tirol, Austria.

Scholars in Athens loveeed to trash the Spartans haha 😊

About the Text: Aristotle is in the midst of explicating the various constituent parts of happiness, which are among the premises an orator must know to be maximally persuasive. In the section from where I pull the passage below, Aristotle discusses ‘possession of many good children’. He explains that the happiness of a community includes many things, including that its young men be many and of good quality—I estimate that this is for the sake of having good soldiers and statesmen.

[A disclaimer must be given for Aristotle’s views on women: my, my friends’ and mentors’ judgment, through many years studying his works, is that Aristotle is highly misogynistic. Many passages support our claim, some of which I will share in the future *not* to endorse his views, but so as to give a full picture of his theory.]

Immediately preceding today’s passage, he discusses his idea that women must also, like men, achieve excellences of body and soul that are suitable for them; the excellences women may achieve are, he thinks, different in kind from that of men, for women are different in kind from men. (‘Different in kind’ is accurate, but is also the nicest way I can phrase Aristotle’s view.) Thus, societies that do not promote women and men flourishing in the ways suitable for them, he thinks, are half-unhappy. His example is of the Lacedaemonians—another (older) name for the Spartans.

Rhetoric I.5.6 1361a11-13:

“…and similarly, for both the individual and the community, it is necessary to pursue the existence of these [excellences] in both their men and women; for those city-states where the state of women is bad, e.g. the Lacedaemonians, it is almost as if half are unhappy.”

ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ ἰδίᾳ καὶ κοινῇ καὶ κατ’ ἄνδρας καὶ κατὰ γυναῖκας δεῖ ζητεῖν ἕκαστον ὑπάρχειν τῶν τοιούτων‧ ὅσοις γὰρ τὰ κατὰ γυναῖκας φαῦλα ὥσπερ Λακεδαιμονίοις, σχεδὸν κατὰ τὸ ἥμισυ οὐκ εὐδαιμονοῦσιν.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Freese (1924) and Roberts (1924).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako in Aliko Beach, Naxos, Cyclades, Greece.

“America is less of a democracy and more of an oligarchy than we like to think.” Not sure I agree with this claim, but it was literally in an article by Paul Krugman I read THIS MORNING. By the way, Aristotle thinks democracy is awful.

About the Text: Why is this text in the Rhetoric? This sounds like politics, no? I know right. Well, basically, Aristotle thinks that in order to be a good orator, one needs three things: (1) the ability to reason logically, (2) an understanding of human characters, and (3) an understanding of human emotions (1356a22-25). In modern terms, I’d say these three translate to something approximating (1) IQ, (2) an understanding of psychology, and (3) EQ. Aristotle thinks that, in order to reason logically, you need to have the correct premises and to make proper deductions (i.e. demonstrations/proofs) from those premises. Today’s text is discussing deliberative rhetoric, the sort used to persuade legislative bodies to do one thing or another in Athens’ political sphere… thus, one must have knowledge about political structures to provide the correct premises from which to produce deductions.

Rhetoric I.4.12 1360a18-28:

“For the sake of security, it is necessary that the orator is able to behold all these things, but most of all to understand the legislation, for the security of the city-state depends on the laws…. All the others [i.e. all the forms of government excluding the perfect one] are destroyed either by being too relaxed or by being too strained. For example, democracy becomes weaker so that it will end in oligarchy not only if it is too relaxed [but also if it is too strained].”

Εἰς δ’ ἀσφάλειαν ἅπαντα μὲν ταῦτα ἀναγκαῖον δύνασθαι θεωρεῖν, οὐκ ἐλάχιστον δὲ περὶ νομοθεσίας ἐπαϊειν‧ ἐν γὰρ τοῖς νόμοις ἐστὶν ἡ σωτηρία τῆς πόλεως…. αἱ ἄλλαι πᾶσαι καὶ ἀνιέμεναι καὶ ἐπιτεινόμεναι φθείρονται οἷον δημοκρατία οὐ μόνον ἀνιεμένη ἀσθενεστέρα γίνεται ὥστε τέλος ἥξει εἰσ ὀλιγαρχίαν….

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Freese (1924) and Roberts (1924), and a bit of Cope (1877).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako in the National Garden in Athens.

Bonus Caption: It’s time the world sees a philosopher-QUEEN… I’ve been joking about this for years now, but given all the craziness lately, maybe worth a try! How about Martha Nussbaum or Sarah Broadie or Rachel Barney? I’m down.

“But Aristotle darling, ‘there is no general rule’ sounds like a general rule!”, I said at 18 years old, rolling my eyes as I read the Nicomachean Ethics for the first time….

About the Text: My above sass is actually something scholars have thought about in the last two millennia—let’s leave that for another day. For today let’s reiterate Aristotle’s view that ethics should not involve categorical rules. This is because each individual situation in which an agent may be in contains details that are specific to that particular situation that causally affect what action would be best. It is for this reason that it is crucial for an agent to carefully examine (σκοπεῖν, Fun Fact: micro‘scope’ is from σκοπεῖν!) the circumstances surrounding their decision to act in one way or another if, in fact, they want to do what is best. In the future I will share the particular kinds of details Aristotle thinks one must pay serious attention to (Book III)!

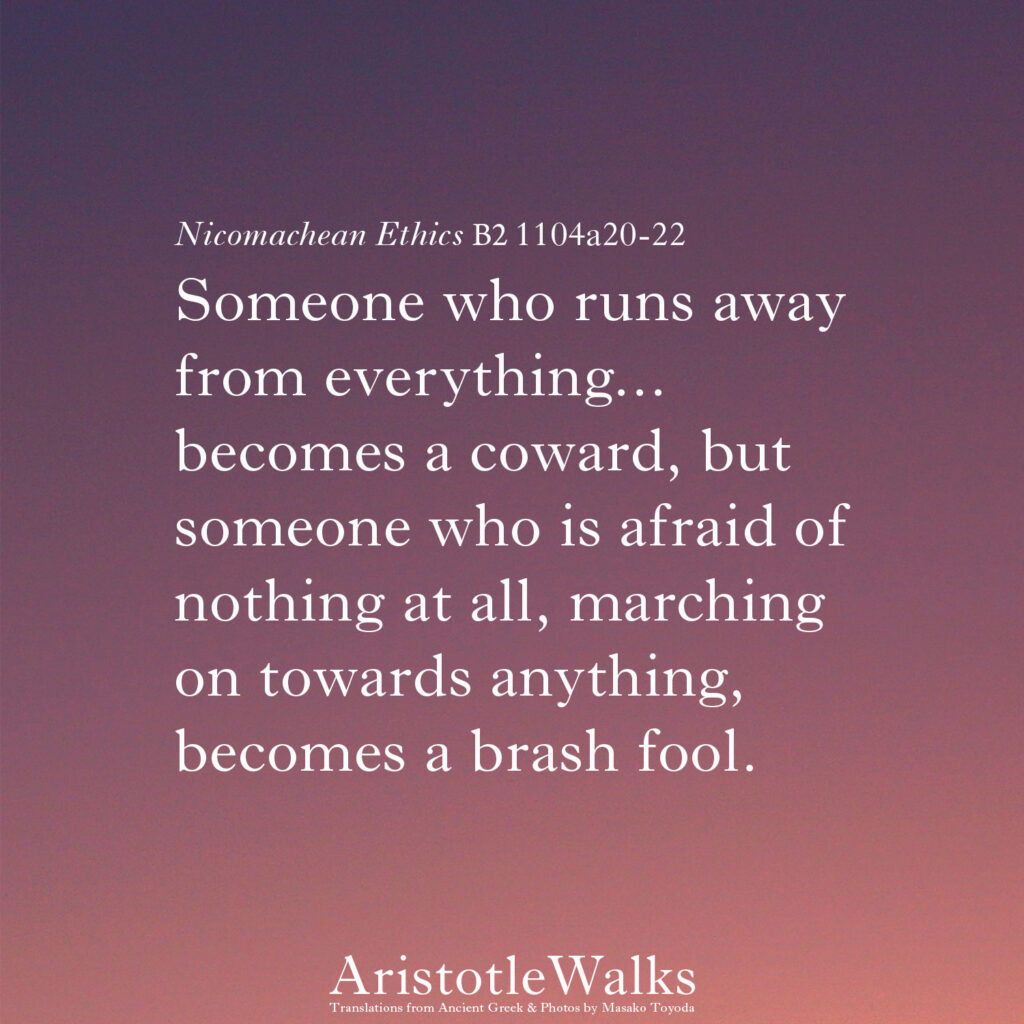

Nicomachean Ethics Β2 1104a3-9:

“The matters regarding actions and the things that are beneficial have nothing fixed, just like how matters of health do not… and it is necessary that the agents themselves always examine the things that promote what is opportune/advantageous.”

τὰ δ’ ἐν ταῖς πράξεσι καὶ τὰ συμφέροντα οὐδὲν ἑστηκὸς ἔχει, ὥσπερ οὐδὲ τὰ ὑγιεινά. τοιούτου δ’ ὄντος τοῦ καθόλου λόγου, ἔτι μᾶλλον ὁ περὶ τῶν καθ’ ἕκαστα λόγος οὐκ ἔχει τἀκριβές… δεῖ δ’ αὐτοὺς ἀεὶ τοὺς πράττοντας τὰ πρὸς τὸν καιρὸν σκοπεῖν… Bywater OCT.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako at Mystique, Oia, Santorini, Cyclades, Greece.

Bonus caption: “I didn’t know how deeply I’d fall in love, then”, she said in third person, exhausted as she finished writing her 27th daily Aristotle post at 3 am.

It is in your power to read the caption below for the context of this post! haha 😊

About the Text: Today’s text is from Aristotle’s elaboration on the first kind of rhetorical speech—the deliberative kind. Deliberative rhetorical speech aims to establish the expediency/inexpediency or the benefit/harmfulness of a proposed course of action (1358b21-3); and, for completeness (i.e. to continue from yesterday), I add that this kind of rhetoric is for an audience that includes those who deliberate and thus decide on what will be done (in politics, e.g. a public assembly). Aristotle sets out to figure out the scope of deliberative rhetoric. He excludes topics that are already past or inevitable in the future, things that are impossible, and also things that occur naturally or by accident. For these things deliberative rhetoric is useless…. Instead… [today’s passage!].

Rhetoric I.4.3 1358a35-b2:

“…but it is clear that council concerns what is subject to deliberation, that which is natural for us to take up and for which the principle of generation is in us. For we examine things until this point, until we find out whether or not to act is in our power.”

…ἀλλὰ δῆλον ὅτι περὶ ὅσων ἐστὶ τὸ βουλεύεσθαι. τοιαῦτα δ’ ἐστὶν ὅσα πέφυκεν ἀνάγεσθαι εἰς ἡμᾶς, καὶ ὧν ἡ ἀρχὴ τῆς γενέσεως ἐφ’ ἡμῖν ἐστίν‧ μέχρι γὰρ τούτου σκοποῦμεν, ἕως ἂ εὕρωμεν εἰ ἡμῖν δυνατὰ ἢ ἀδύνατα πρᾶξαι.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Freese (1924) and Roberts (1924), as well as Cope (1877).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako at Syntagma in Athens, Greece.

Have you said something lately without considering who you were talking to? Haha, I have, too. On another note, I’m debating making the captions song lyrics that illustrate the text. @leah.fuku But “there’s an ancient feud between poetry and philosophy” (Plato, Republic 607b), so maybe not. Today’s would have been: ‘It’s not up to you, oh it never really was’.

About the Text: Today’s text from Book I Chapter 3 of Aristotle’s Rhetoric directly precedes his list of the three kinds of rhetorical speeches upon which he will expand: (1) deliberative, (2) forensic, and (3) epideictic. The determining aspect for each kind of rhetorical speech, i.e. what differentiates each of these, is the audience who is to listen to the speech. In other words, the sort of speech one must use, i.e. the sort that will produce the desired effect of rhetoric—persuasion—is contingent on the sorts of people in the audience… and *not* on the speaker nor on the subject matter… I repeat, *not* on the speaker nor on the subject matter…. I will expand on the kinds of speeches in future posts! 😊

Rhetoric I.3.1 1358a35-b2:

“The kinds of rhetoric are three in number, for that is how many kinds of listeners there are. For of the three elements that make up speech—the speaker, the topic and the one addressed—it is the one addressed on which the end depends; I mean, on the listener.”

ἔστι δὲ τῆς ῥητορικῆς εἴδη τρία τὸν ἀριθμόν‧ τοσοῦτοι γὰρ καὶ οἱ ἀκροαταὶ τῶν λόγων ὑπάρχουσιν ὄντες. Σύγκειται μὲν γὰρ ἐκ τριῶν ὁ λόγος, ἔκ τε τοῦ λέγοντος καὶ περὶ οὗ λέγει καὶ πρὸς ὅν, καὶ τὸ τέλος πρὸς τοῦτόν ἐστι, λέγω δὲ τὸν ἀκροατήν.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Freese (1924) and Roberts (1924), as well as Cope (1877).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako on Oia, Santorini, Cyclades, Greece.

‘Can’ does not mean ‘should’. Bae does NOT condone this behavior.

About the Text: To continue from yesterday, today’s passage is one where Aristotle elaborates on the next mode of persuasion in oratory: persuasion (2) ‘by putting the audience in a certain frame of mind’. In Aristotle’s view, emotions, quite literally the thing by which one is affected, *distort* one’s judgments on the information being presented (to my friends/colleagues/mentors who have also been studying Aristotle for years, please always object in the comments if you disagree with anything I say).

Rhetoric I.2.5 1356a13-16:

“And [persuasion occurs] through the audience members, when they are led by the speech to emotion, for we do not deliver judgments in the same way when we are grieving or rejoicing, loving or hating. It is towards this [effect] alone that, as we have said, contemporary writers on rhetoric endeavor to focus.”

διὰ δὲ τῶν ἀκροατῶν, ὅταν εἰς πάθος ὑπὸ τοῦ λόγου προαχθῶσιν· οὐ γὰρ ὁμοίως ἀποδίδομεν τὰς κρίσεις λυπούμενοι καὶ χαίροντες ἢ φιλοῦντες καὶ μισοῦντες· τοῖς πρὸς ὃ καὶ μόνον πειρᾶσθαί φαμεν πραγματεεσθαι τοὺς νῦν τεχνολογοῦντας.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Freese (1924) and Roberts (1924), as well as Cope (1877).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako on Milos, Cyclades, Greece.

About the Text: Preceding today’s passage, Aristotle says that there are three modes of persuading people by oration: (1) by personal character, (2) by putting the audience in a certain frame of mind, and (3) by reasoned arguments. In today’s passage, Aristotle elaborates on what he means regarding the phenomenon of ‘persuasion by personal character (ἦθος)’. This occurs when speech is delivered in a way so as to make the audience think that the speaker is credible and deserving of our confidence… [insert passage below! 😊]

Rhetoric I.2.4 1356a6-11:

“…for we trust good people more as well as more quickly, concerning generally everything, but for things which there is no certainty but rather room for doubt, [we trust them] even absolutely. But [for this to count as persuasion by personal character in oration,] it must be the case that this occurs through the speech, and not through some pre-judged idea of the one speaking.”

τοῖς γὰρ ἐπιεικέσι πιστεύομεν μᾶλλον καὶ θᾶττον, περὶ πάντων μὲν ἁπλῶς, ἐν οἷς δὲ τὸ ἀκριβὲς μη ἐστιν ἀλλὰ τὸ ἀμφιδοξεῖν, καὶ παντελῶς. δεῖ δὲ καὶ τοῦτο συμβαίνειν διὰ τὸν λόγον, ἀλλὰ μὴ διὰ τὸ προδεδοξάσθαι ποιόν τινα εἶναι τὸν λέγοντα·

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Freese (1924) and Roberts (1924), as well as Cope (1877).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako on Naxos, Cyclades, Greece.

How much of reality have you chosen to ignore?

About the Text: Today’s passage is also (as was yesterday’s) from the beginning of the Rhetoric. Aristotle is in the midst of talking about the reasons why the art of rhetoric is useful, and in our passage he illustrates two important reasons for this (see below!). Other reasons for why rhetoric is useful that surround our passage include but are not limited to: 1) the art of rhetoric helps us get closer to the truth (because the true and the approximately true are grasped by the same faculty of mind/soul) and 2) rhetoric helps us deal with people for whom facts have no force, i.e. illogical people; rhetoric is necessary to convince them.

Side note! My personal Facebook bio for the past 4 years or so has been J.S. Mill’s quote “He who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that.” From On Liberty, 1859).

Rhetoric I.1.12 1355a29-34:

“And further, it is necessary to be able to persuade [others of] the opposites, just as in syllogisms, not so that we may do both (for we must not persuade [others of] the wrong thing), but in order that how things [in fact] are may not escape our notice and so that when another person makes use of arguments unjustly, we may undo them.”

Better English: “Further, it is necessary to be able to persuade others of opposite positions, just as in deductions, not so we may do so (since it is wrong to persuade others of the wrong thing) but so the facts of the matter do not escape our notice and so when others argue unjustly, we may refute them.”

ἔτι δὲ τἀναντία δεῖ δύνασθαι πείθειν, καθάπερ καὶ ἐν τοῖς συλλογισμοῖς, οὐχ ὅπως ἀμφότερα πράττωμεν (οὐ γὰρ δεῖ τὰ φαῦλα πείθειν) ἀλλ’ ἵνα μήτε λανθάνῃ πῶς ἔχει, καὶ ὅπως ἄλλου χρωμένου τοῖς λόγοις μὴ δικαίως αὐτοὶ λύειν ἔχωμεν.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Freese (1924) and Roberts (1924), as well as Cope (1877).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako in Sifnos Island, Greece.

Thus, judges should be left to judge as little as possible…. no joke he explicitly says so.

About the Text: Today’s passage illustrates the third and most important reason for Aristotle’s claim that good laws are the ones that are 1) as well-defined as and 2) leave as little to the judge and jury of a court as possible (1354a32). The first reason for this is that there are very few sensible people that are capable of legislating and administering justice, i.e. it will be difficult to find many sensible people to be judges and easier to find a very few sensible people to set laws. The second reason for this is that laws are set down after long consideration and are thus more thoughtful than the decisions given in court—which are necessarily decided upon relatively quickly. The third reason for this is that the lawmaker sets laws prospectively and universally, whereas… [insert passage below]. These three reasons are together intended to support the claim that judges should be allowed to decide as few things as possible.

Rhetoric I.1.7 1354b7-12:

“…the member of the public assembly and the jury immediately judge the present and particular cases. Towards these, love, hate, or personal interest is often involved, in such a way that they are no longer able to see sufficiently the truth, but rather they obscure their judgment by their own pleasure or pain.”

ὁ δ’ ἐκκλησιαστὴς καὶ δικαστὴς ἤδη περὶ παρόντων καὶ ἀφωρισμένων κρίνουσιν‧ πρὸς οὕς καὶ τὸ φιλεῖν ἤδη καὶ τὸ μισεῖν καὶ τὸ ἴδιον συμφέρον συνήρτηται πολλάκις, ὥστε μηκέτι δύνασθαι θεωρεῖν ἱκανῶς τὸ ἀληθές, ἀλλ’ ἐπισκοτεῖν τῇ κρίσει τὸ ἴδιον ἡδὺ ἢ λυπηρόν.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Freese (1924) and Roberts (1924), as well as Cope (1877).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako street art in Lisboa, Portugal.

…do be do be do…. – Frank Sinatra

About the Text: This is one of his most famous analogies. In this passage Aristotle is in the midst of arguing for the necessity of action for the fulfillment of an excellent human life. It does not matter that if you were to enter and compete in the Games you would win… if you do not. To win the prizes of a good life, namely, to achieve eudaimonia, i.e. flourishing, it is not enough to merely be the sort of person who is capable of discerning what the right things to do are and also capable of doing the right things… one must actually do them.

Nicomachean Ethics Α8 1099a2-7:

“And just as in the Olympic Games, it is not the best and mightiest that are crowned, but the ones competing for the prize (for only some of these athletes may win); thus also the ones who act correctly are the ones that are crowned the noble and good things in life.”

ὥσπερ δ’ ‘Ολυμπίασιν οὐχ οἱ κάλλιστοι καὶ ἰσχυρότατοι στεφανοῦνται ἀλλ’ οἱ ἀγωνιζόμενοι (τούτων γάρ τινες νικῶσιν), οὕτω καὶ τῶν ἐν τῷ βίῳ καλῶν κἀγαθῶν οἱ πράττοντες ὀρθῶς ἐπήβολοι γίνονται. Bywater OCT.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako at Kastro on Sifnos Island, Cyclades, Greece.

“but I feel I’m right about everything”

About the Text: These lines are taken from the part of the text where Aristotle discusses the sort of thing we are looking for in the Nicomachean Ethics, an inquiry into how to lead a good life. Aristotle’s usual method of inquiry is to look at multiple endoxa, opinions that are popular or held by experts that have some sort of argument in favor for it, and to extract what is good and right from each. There are positions Aristotle outright rejects as ridiculous, but more often than not he considers others’ positions seriously and refutes only the parts of them that do not make sense and incorporates the good bits into his own philosophy.

Nicomachean Ethics Α8 1098b23-29:

“And it appears that the things being sought about eudaimonia (happiness / flourishing) has all already been laid down. For to some it seems to be virtue, to others phronesis (practical wisdom/prudence), and to others wisdom. To others it seems to be all these or some of these alongside pleasure or not without pleasure. Others further add external prosperity. Some of these views are held by many and traditional, others are held by few widely esteemed people. Neither are entirely mistaken, but rather they are right in some or even many respects.”

Φαίνεται δὲ καὶ τὰ ἐπιζητούμενα τὰ περὶ τὴν εὐδαιμονίαν ἅπανθ’ ὑπάρχειν τῷ λεχθέντι. τοῖς μὲν γὰρ ἀρετὴ τοῖς δὲ φρόνησις ἄλλοις δὲ σοφία τις εἶναι δοκεῖ, τοῖς δὲ ταῦτα ἢ τούτων τι μεθ’ ἡδονῆς ἢ οὐκ ἄνευ ἡδονῆς‧ ἕτεροι δὲ καὶ τὴν ἐκτὸς εὐετηρίαν συμπαραλαμβάνουσιν. τούτων δὲ τὰ μὲν πολλοὶ καὶ παλαιοὶ λέγουσιν, τὰ δὲ ὀλίγοι καὶ ἔνδοξοι ἄνδρες‧ οὐδετέρους δὲ τούτων εὔλογον διαμαρτάνειν τοῖς ὅλοις, ἀλλ’ ἕν γέ τι ἢ καὶ τὰ πλεῖστα κατορθοῦν. Bywater OCT.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako of the Temple of Hephaestus in the Agora of Athens, Greece.

What’ll be your final life score? 😉 (ft. the Good Place)

About the Text: These lines are taken from one of the most famous parts of the Aristotelian corpus. Book I Chapter 7 in the OCT (which is Alpha 6 in Bekker) contains the famous, famous function (ergon) argument for which I will have to do many more future posts to do justice to the idea. For now, I would like to familiarize you with the idea that Aristotle thinks human beings have a function to fulfill, that this function is to partake in activity that is in accordance with reason, and that it is to do so *throughout* one’s life.

Nicomachean Ethics Α6 1098a7-8, 16-20:

“And if the function of a human being is ‘the activity of the soul according to reason or not without reason’ […and if other assumptions…], then the human good turns out to be ‘activity of the soul in accordance with virtue. And we must add, ‘in a complete life’. For, one swallow does not make a spring, nor does one day. And in this way, neither blessed nor eudaimonious does one day [make a person], nor a short time.”

εἰ δ’ ἐστὶν ἔργον ἀνθρώπου ψυχῆς ἐνέργεια κατὰ λόγον ἢ μὴ ἄνευ λόγου…. τὸ ἀνθρώπινον ἀγαθὸν ψυχῆς ἐνέργεια γίνεται κατ’ ἀρετήν, εἰ δ’ ἐν βίῳ τελείῳ. μία γὰρ χελιδὼν ἔαρ οὐ ποιεῖ, οὐδὲ μία ἡμέρα‧ οὕτω δὲ οὐδὲ μακάριον καὶ εὐδαίμονα μία ἡμέρα οὐδ’ ὀλίγος χρόνος. Bywater OCT.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako in Tirol, Austria.

Aristotle, woke af.

About the Text: This passage is pulled from the part of the text within which Aristotle discusses the three kinds of lives: 1) of pleasure, 2) of politics, and 3) of study. Each of these three has a corresponding good that it pursues. The second is our subject of study today, the life of politics. Athenian citizens (only the wealthiest 10% of the people who lived in or by Athens) participated in the life of politics and as such pursued honor, Aristotle says. Aristotle thinks this life is not so great, to put it mildly….

Nicomachean Ethics Α3 1095b22-30:

“The accomplished and pragmatic people pursue honor, for this is roughly speaking the telos (i.e. the end, goal) of the political life. But honor appears to be more superficial than what we’re looking for, since it seems to depend more on the people who honor than on the person being honored, and we’d expect the good to be something proper to and hard to take away from the one who has achieved it. Further, people who seek honor seem to pursue it to convince themselves as good; they at least seek to be honored by the wise men, among those who know them, and for virtue. It is thus clear that—in *their* view— virtue is superior to honor.”

οἱ δὲ χαρίεντες καὶ πρακτικοὶ τιμήν‧ τοῦ γὰρ πολιτικοῦ βίου σχεδὸν τοῦτο τέλος. φαίνεται δ’ ἐπιπολαιότερον εἶναι τοῦ ζητουμένου‧ δοκεῖ γὰρ ἐν τοῖς τιμῶσι μᾶλλον εἶναι ἢ ἐν τῷ τιμωμένῳ, τἀγαθὸν δὲ οἰκεῖόν τι καὶ δυσαφαίρετον εἶναι μαντευόμεθα. ἔτι δ’ ἐοίκασι τὴν τιμὴν διώκειν ἵνα πιστεύσωσιν ἑαυτοὺς ἀγαθοὺς εἶναι‧ ζητοῦσι γοῦν ὑπὸ τῶν φρονίμων τιμᾶσθαι, καὶ παρ’ οἷς γινώσκονται, καὶ ἐπ’ ἀρετῇ‧ δῆλον οὖν ὅτι κατά γε τούτους ἡ ἀρετὴ κρείττων. Bywater OCT.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako on Hydra island, Greece.

Do you consider what is good for you to be obvious and clear?

About the Text: This passage is pulled from the chapter within which Aristotle discusses the importance of considering the credible varieties of common beliefs (endoxa) to extract the good and useful things and to reject the bad and unhelpful bits. He thinks this is a good starting point in the study of ethics—to gather multiple view points and analyze them before beginning to form one’s opinion (he intimates this in the Ethics, but it is explicit in his Topics and Rhetoric). *Most* of the opinions of the common people (hoi polloi), however, he does not here find compelling.

Nicomachean Ethics Α2 1095a20-26:

“But regarding what flourishing is, they dispute, and hoi polloi do not give the same answer as the wise. For some think that it is something obvious and clear—for example, pleasure, wealth or honor. Others think that it is something else. And often the same person thinks that it is another [i.e. the same person changes their mind], for when one is ill, one thinks it is health; when one is poor, one thinks it is wealth. And when they are aware of their own ignorance, they are in awe of whoever says big things that are beyond them.”

περὶ δὲ τῆς εὐδαιμονίας, τί ἐστιν, ἀμφισβητοῦσι καὶ οὐχ ὁμοίως οἱ πολλοὶ τοῖς σοφοῖς ἀποδιδόασιν. οἳ μὲν γὰρ τῶν ἐναργῶν τι καὶ φανερῶν, οἷον ἡδονὴν ἢ πλοῦτον ἢ τιμήν, ἄλλοι δ’ ἄλλο–πολλάκις δὲ καὶ ὁ αὐτὸς ἕτερον‧ νοσήσας μὲν γὰρ ὑγίειαν, πενόμενος δὲ πλοῦτον‧ συνειδότες δ’ ἑαυτοῖς ἄγνοιαν τοὺς μέγα τι καὶ ὑπὲρ αὐτοὺς λέγοντας θαυμάζουσιν. From Bywater OCT.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004). In translating εὐδαιμονία as ‘flourishing’ instead of happiness, I follow Cooper (1975).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako in Sifnos Island, Cyclades, Greece.

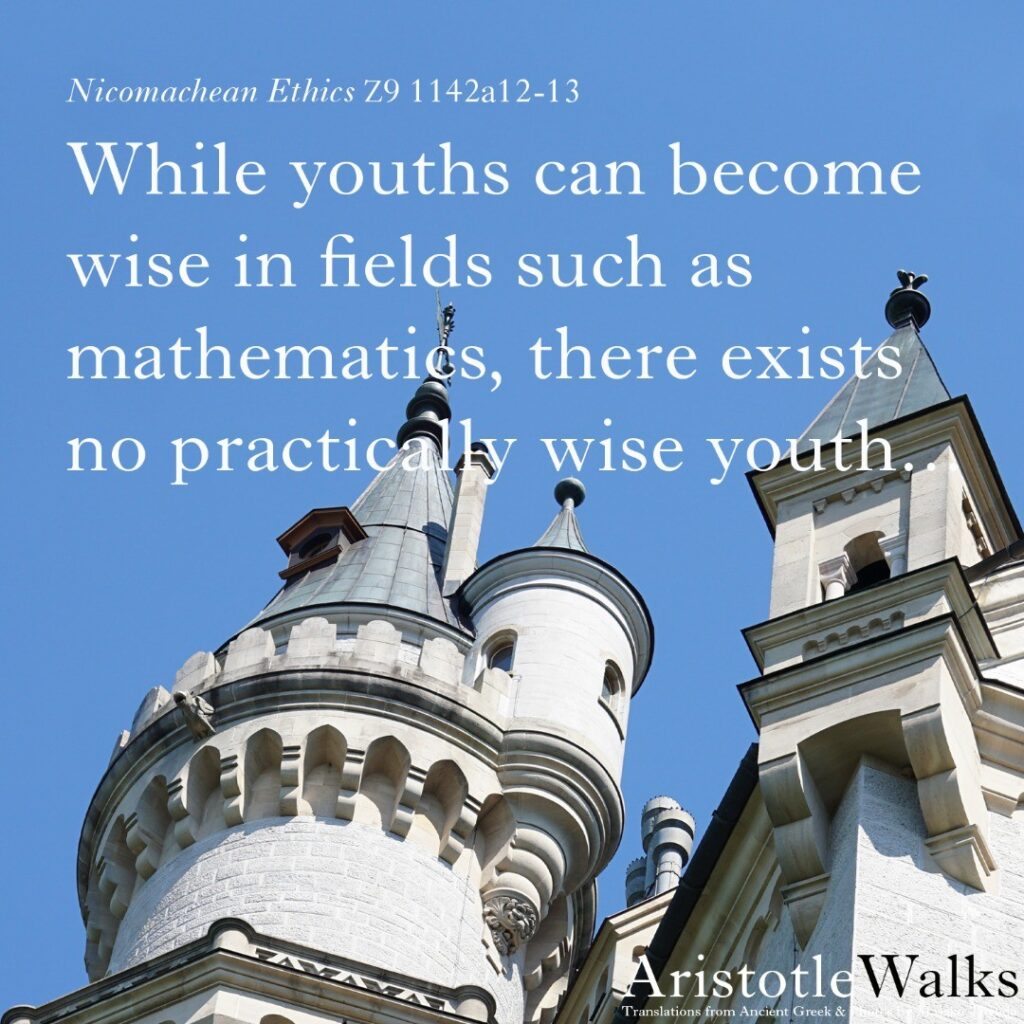

Do you think you’re a good judge of all things?

About the Text: The shoemaker judges well the activity of shoemaking, the doctor judges well the activity of healing the body, and the excellent person judges well things to do with excellent things, like justice, courage, generosity. In order to judge well things of a particular field, you must have first studied that field well. Aristotle thinks it is difficult to study even one field of study well (See his Analytics); he thinks that it is *extremely* difficult to become a good judge of all things. Indeed, for the rest of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle sets forth a view within which becoming an excellent person is a long and difficult process.

The last sentence of the passage below is extremely famous, and I will address it in a future post!

Nicomachean Ethics A1 1094b27-1095a3:

“And each person judges well the things he knows and of these are a good judge. Thus, the person who has been educated in a field of knowledge judges well things in that field, and the person who has been educated in all areas of knowledge judges well, simpliciter. Because of this, a young person is not a suitable student of political science, for they are inexperienced in the actions concerning life.”

[‘simpliciter’ is Latin for unconditionally, simply… or unqualifiedly in Aristotelian literature; Aristotle says that the subject of the Nicomachean Ethics is ‘political science’… when he says ‘political science’ in Greek, he refers, roughly speaking, to the field of study we now know as Ethics.]

ἕκαστος δὲ κρίνει καλῶς ἃ γινώσκει, καὶ τούτων ἐστὶν ἀγαθὸς κριτής. καθ’ ἕκαστον μὲν ἄρα ὁ πεπαιδυμένος, ἁπλῶς δ’ ὁ περὶ πᾶν πεπαιδευμένος. διὸ τῆς πολιτικῆς οὐκ ἔστιν οἰκεῖος ἀκροατὴς ὁ νέος‧ ἄπειρος γὰρ τῶν κατὰ τὸν βίον πράξεων… from Bywater OCT.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako in Naxos Island, Cyclades, Greece.

so that person with a different political view you think is evil? …yeah, probably not.

About the Text: This passage is from the first few lines of Aristotle’s famous Politics. Aristotle, following Socrates/Plato, thinks that everyone pursues what they think is good. As is clear from a variety of texts, most tellingly Book I of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle thinks that many people are mistaken; the many (or, ὁι πολλοί *hoi polloi*) often mistake pleasure, wealth, or honor for what is good. So appearances can be deceiving, but, he thinks, everyone pursues what seems to them as good…. so just don’t be wrong 😉

Politics A1 1252a1-6:

“Since we observe that every city is some kind of partnership, and every partnership is formed for the sake of some good—for, all people act for the sake of something that appears to be good—it is thus clear that while all aim at some good, the political partnership, which is most supreme and encompassing all the others, aims at the most supreme of all and highest good.”

ἐπειδὴ πᾶσαν πόλιν ὁρῶμεν κοινωνίαν τινὰ οὖσαν καὶ πᾶσαν κοινωνίαν ἀγαθοῦ τινος ἕνεκεν συνεστηκυῖαν—τοῦ γὰρ εἶναι δοκοῦντος ἀγαθοῦ χάριν πάντα πράττουσι πάντες—δῆλον ὡς πᾶσαι μὲν ἀγαθοῦ τινος στοχάζονται, μάλιστα δὲ καὶ τοῦ κυριωτάτου πάντων ἡ πασῶν κυριωτάτη καὶ πάσας περιέχουσα τὰς ἄλλας. Ross (1957)

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Jowett (1885) and Rackham (1944).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako of Hadrian’s Arc in Plaka, Athens, Greece.

Aristotle’s private letter to Kant, circa 330 BC.

About the Text: Ethics, for Aristotle, is objective (s/o @rossbrohanson). What is interesting about Aristotle’s ethics is that, at the same time that he thinks it is objective, he also thinks it should not involve universal claims (e.g. lying is always bad). This is because of the nature of ethics (a huge topic).

To formulate it differently, Aristotle thinks there are many generally good rules of thumb, but also that there are always exceptions to them (Aristotle famously claims two exceptions to this! I’ll post them in the future). For example, though it is true, generally, that one should help one’s friends attain their goals… if a friend aims to buy heroin, you should not in that case help that friend—or, at least I think so *wink*.

If you would have questions about this passage, please post in the comments of the post! I will always do my best to answer you.

Nicomachean Ethics Α1 1094b19-22:

“One must be content, then, while speaking about these sorts of things [i.e. matters of political science] and from these sorts of premises, to demonstrate the truth coarsely and in outline. And while speaking about thing which hold only for the most part and from these sorts of premises, [one must be content] also to draw conclusions of the same sort.”

ἀγαπητὸν οὖν περὶ τοιούτων [20] καὶ ἐκ τοιούτων λέγοντας παχυλῶς καὶ τύπῳ τἀληθὲς ἐνδείκνυσθαι, καὶ περὶ τῶν ὡς ἐπὶ τὸ πολὺ καὶ ἐκ τοιούτων λέγοντας τοιαῦτα καὶ συμπεραίνεσθαι.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako in Sifnos Island, Cyclades, Greece.

Swans are most of all animals prone to eat each other, says Aristotle, a few lines earlier.

About the Text: A third of the surviving text we have of Aristotle is on… biology! Historia Animalium, or “τῶν περὶ τὰ ζῷα ἱστοριῶν” which directly translates to “of researches concerning the animals”, is a 152 Bekker page (compare: the Nicomachean Ethics is 87 Bekker pages!) collection of empirical data Aristotle compiled on animals. Generally speaking, Aristotle’s other biological works offer philosophical analysis of the compiled data in Historia Animalium. Today’s passage comes from HA, right after Aristotle says swans are the animals most likely to eat each other and right before Aristotle says the donkey and akanthis are at war.

Historia Animalium Θ(I)1 610a3-4:

And there are of the wild animals, some that are always at war with each other and others that are only on occasion, like humans.

ἔστι δὲ τῶν θηρίων τὰ μὲν ἀεὶ ποέμια ἀλλήλοις, τὰ δ’ ὥσπερ ἄνθρωποι ὅταν τύχωσιν.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Cresswell (1862) and Thompson (1910).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako in Kyoto, Japan.

But don’t be fooled 😉

About the Text: This passage is near the beginning of the Nicomachean Ethics where Aristotle discusses how this field (political science) should be studied. The nature of ethics, a field of study concerning actions, each of which necessarily has many individual peculiarities in the circumstantial details, Aristotle will claim in a passage I will share in a day or two, is one which calls for rules that hold *only for the most part* but not universally. For today’s passage, what is relevant is that the nature of ethics is one such that there *seems* to be so much variation… so much so that it seems like there may not be any objective claims to make whatsoever. This idea, Aristotle rejects very much.

Nichomachean Ethics A1 1094b14–19:

Fine and just things–which political science investigates–differ and vary greatly, so that it may appear as though they are what they are by convention only, and not by nature. But goods also vary in the same way, when we consider the harms befalling many people because of them. For, some have died because of wealth, others because of courage.

τὰ δὲ καλὰ καὶ τὰ δίκαια, περὶ ὧν ἡ πολιτικὴ σκοπεῖται, πολλὴν ἔχει διαφορὰν καὶ πλάνην, ὥστε δοκεῖν νόμῳ μόνον εἶναι, φύσει δὲ μή. τοιαύτην δέ τινα πλάνην ἔχει καὶ τἀγαθὰ διὰ τὸ πολλοῖς συμβαίνειν βλάβας ἀπ’ αὐτῶν‧ ἤδη γάρ τινες ἀπώλοντο διὰ πλοῦτον, ἕτεροι δὲ δι’ ἀνδρείαν. (Bywater, OCT).

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako sunset from the island of Hyrda, Greece.

Quiz: Is Aristotle alive today or did he die 2343 years ago?

About the Text: This passage is found near the very beginning of the two books (Θ & Ι, or otherwise 8 & 9) Aristotle dedicates to the topic of friendship. In the earlier books in the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle discusses many topics that relate to how a person can live a good life, e.g. the virtues of character, an understanding of agency, justice—but in books 8 & 9 he discusses friendship as something “most necessary for life”. In this particular passage, he empirically observes that friendship is held in even higher esteem than justice by the politicians of a city.

Nicomachean Ethics Θ 1 1155a22-28:

“And friendship (φιλία) seems also to hold cities together, and lawmakers seem to care more about it than about justice (δικαιοσύνη), for harmony (ὁμόνοια, agreement, unanimity) seems to be something similar to friendship, and they aim at this (i.e. ὁμόνοια) most of all, and they drive out civil conflict as most hostile of all. When people are friends, there is no need of justice, but when they are [merely] just, they additionally need friendship; and the highest form of justice seems to be of a friendly quality.”

ἔοικε δὲ καὶ τὰς πόλεις συνέχειν ἡ φιλία, καὶ οἱ νομοθέται μᾶλλον περὶ αὐτὴν σπουδάζειν ἢ τὴν δικαιοσύνην ‧ ἡ γὰρ ὁμόνοια ὅμοιόν τι τῇ φιλίᾳ ἔοικεν εἶναι, ταύτης δὲ μάλιστ’ ἐφίενται καὶ τὴν στάσιν ἔχθραν οὖσαν μάλιστα ἐξελαύνουσιν ‧ καὶ φίλων μὲν ὄντων οὐδὲν δεῖ δικαιοσύνης, δίκαιοι δ’ ὄντες προσδέονται φιλίας, καὶ τῶν δικαίων τὸ μάλιστα φιλικὸν εἶναι δοκεῖ.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Ross (1925), Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako at Sarakiniko Beach, Milos Island, Cyclades, Greece.

Which are you?

About the Text: The passage from which the quote above is taken is one of the most famous passages in Corpus Aristotelicum. We get Aristotle’s definition of episteme, scientific ‘knowledge’ or otherwise translated as ‘understanding’, here. Two conditions must be met for X to be considered ‘known’ in this very strict way (ἐπίσταμαι): 1. the cause of X must be known (in a weaker sense, γιγνώσκω) and 2. X cannot be otherwise. Of course questions arise as to how to know whether these conditions have been met, and of course the answers to these questions are hotly debated!

Posterior Analytics A 2 71b9-16

We think (οἴομαι) that we know (ἐπίσταμαι) something unqualifiedly–and not in the sophistic way, i.e. accidentally–whenever we think (οἴομαι) that we know (γιγνώσκω) the cause (αἰτία) on which the matter depends that it is the cause of it and that it is impossible for it to be otherwise. Well then it is clear that to know (ἐπίσταμαι) is something of this sort, for, the ones who do not know (ἐπίσταμαι) and the ones who do know both think (οἴομαι) that it is so, but the latter additionally understands that it is so, with the result that when there is knowledge of something unqualifiedly, that ‘something’ is impossible to be otherwise.

Ἐπίστασθαι δὲ οἰόμεθ’ ἕκαστον ἁπλῶς, ἀλλὰ μὴ τὸν σοφιστικὸν τρόπον τὸν κατὰ συμβεβηκός, ὅταν τήν τ’ αἰτίαν οἰώμεθα γινώσκειν δι’ ἣν τὸ πρᾶγμά ἐστιν, ὅτι ἐκείνου αἰτία ἐστί, καὶ μὴ ἐνδέχεσθαι τοῦτ’ ἄλλως ἔχειν. δῆλον τοίνυν ὁτι τοιοῦτόν τι τὸ ἐπίστασθαί ἐστι ‧ καὶ γὰρ οἱ μὴ ἐπιστάμενοι καὶ οἱ ἐπιστάμενοι οἱ μὲν οἴονται αὐτοὶ οὕτως ἔχειν, οἱ δ’ ἐπιστάμενοι καὶ ἔχουσιν, ὥστε οὗ ἁπλως ἔστιν ἐπιστήμη, τοῦτ’ ἀδύνατον ἄλλως ἔχειν. from Ross (1964), but following Coislinianus 330 for αὐτό at b14.

Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Bouchier (1901), Barnes (1975), and Mure (1994?) & help from @binhkwon

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako on (οἴομαι) Porto Cheli (Χέλι), Peninsula of Argolida by the Argolic Gulf, Greece.

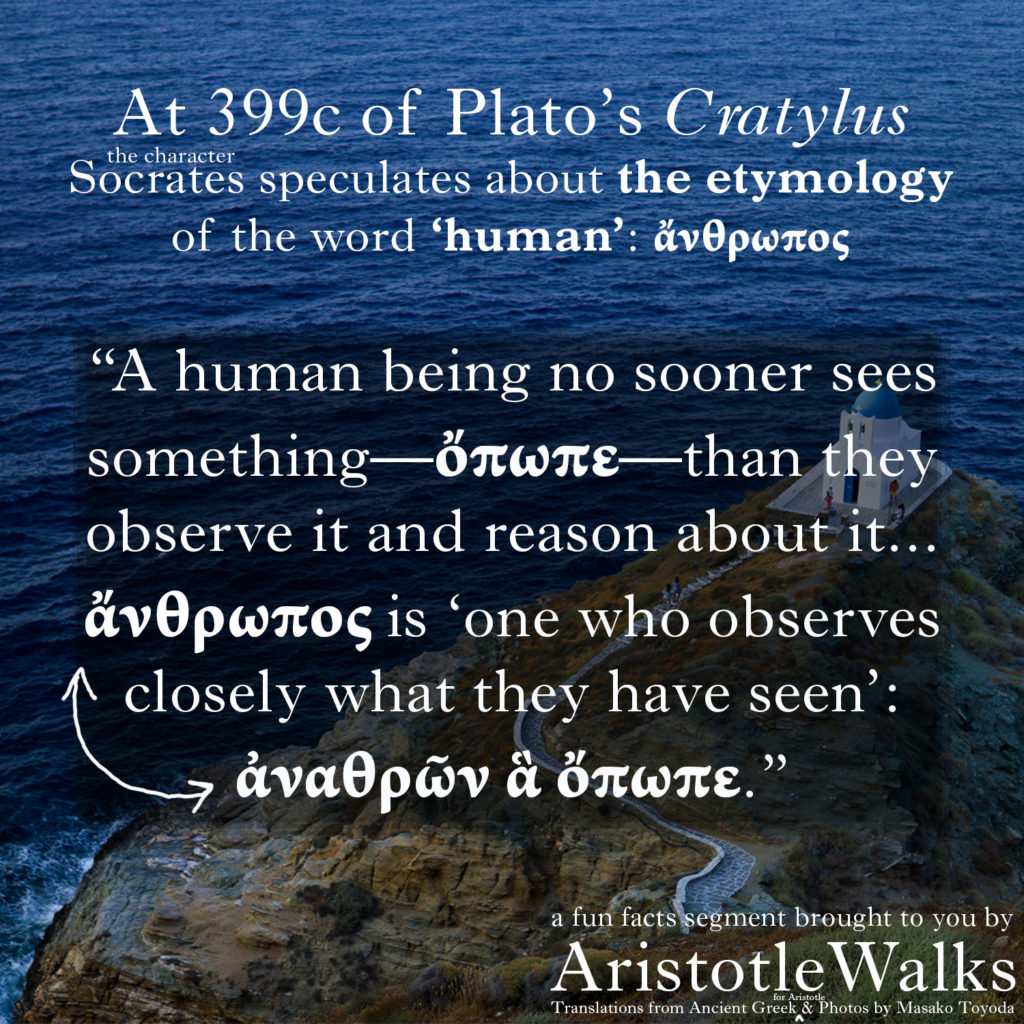

Aristotle was a sapiosexual, a theory.

About the Text: The opening line of Aristotle’s Metaphysics, this sentence is one of the most famous of all found in his corpus. This claim has been widely interpreted to carry with it an optimistic sense–one within which Aristotle seems to posit a natural impulse towards the acquisition of knowledge in a human being, qua human being.

Metaphysics A 1 980a21:

“All human beings by nature desire to know.”

πάντες ἄνθρωποι τοῦ εἰδέναι ὀρέγονται φύσει.

English Translation by @masako.toyoda.

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako of sunset on Naxos Island, Cyclades, Greece.

Aristotle discovered hangry before any of us.

While the exact details of this controversial passage are heavily debated, it is agreed upon as one where Aristotle touches on his view that body and soul are… inseparable.

De Anima A.1 403a16-24:

“And it seems that all of the affections of the soul involve the body–anger, temperateness, fear, pity, courage, as well as joy and loving and hating. For at the same time as these, the body is affected in some way. A sign of this is that sometimes strong and palpable affections occur without being provoked or made afraid, while at other times one is moved by small and almost imperceptible things, e.g. whenever the body is agitated and thus is like when it is angry. This is still more clear from that [sometimes] affections of a frightened person arise without anything frightening occuring.”

ἔοικε δὲ καὶ τὰ τῆς ψυχῆς πάθη πάντα εἶναι μετὰ σώματος, θυμός, πραότης, φόβος, ἔλεος, θάρσος, ἔτι χαρὰ καὶ τὸ φιλεῖν τε καὶ μισεῖν ‧ ἅμα γὰρ τούοις πάσχει τι τὸ σῶμα. σημεῖον δὲ τὸ ποτὲ μὲν ἰσχυρῶν καὶ ἐναργῶν παθημάτων συμβαινόντων μηδὲν παροξύνεσθαι ἢ φοβεῖσθαι, ἐνίοτε δ’ ὑπὸ μικρῶν καὶ ἀμαυρῶν κινεῖσθαι, ὅταν ὀργᾷ τὸ σῶμα καὶ οὕτως ἔχῃ ὥσπερ ὅταν ὀργίξηται. ἔτι δὲ τοῦτο μᾶλλον φανερόν ‧ μηθενὸς γὰρ φοβεροῦ συμβαίνοντος ἐν τοῖς πάθεσι γίνονται τοῖς τοῦ φοβουμένου.

English Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Hicks (1907) and Shields (2016).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako on Milos, Cyclades, Greece.

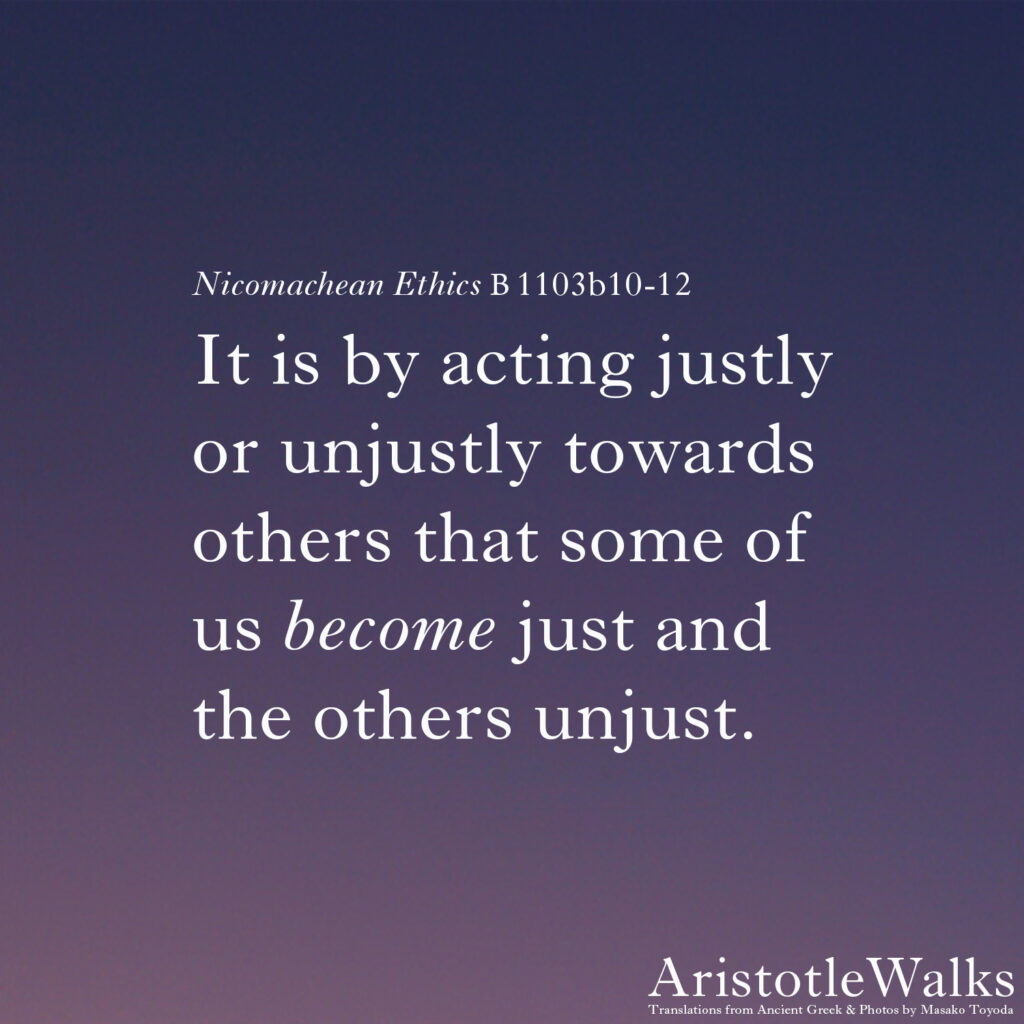

and by doing idiotic actions you too can become an idiot! 🙂

In all seriousness, this is a passage on one of the most famous parts of his ethical treatise: a person *habituates* to different states of excellent or base character. A particular ἀρετή (usually translated as ‘virtue’ but more literally ‘excellence’, e.g. courage, temperance, magnanimity, is acquired through repeating actions of that kind.

Nicomachean Ethics B 1 1103a35-b6, b21-22:

So, then, we become just by doing just actions, temperate by doing temperate actions, and brave by doing brave actions. What happens in the cities is also witness to this, for the law-makers make citizens good by habituation, and this is what all law-makers intend. Those law-makers who do not do this well miss the mark, and it is in this respect that a good political constitution differs from a bad one…. states of character arise [by repetition of] similar activities.

οὕτω δὴ καὶ τὰ μὲν δίκαια πράττοντες δίκαιοι γινόμεθα, τὰ δὲ σώφρονα σώφρονες, τὰ δ’ ἀνδρεῖα ἀνδρεῖοι. μαρτυρεῖ δὲ καὶ τὸ γινόμενον ἐν ταῖς πόλεσιν ‧ οἱ γὰρ νομοθέται τοὺς πολίτας ἐθίζοντες ποιοῦσιν ἀγαθούς, καὶ τὸ μὲν βούλημα παντὸς νομοθέτον τοῦτ’ ἐστίν, ὅσοι δὲ μὴ εὖ αὐτὸ ποιοῦσιν ἁμαρτάνουσιν, καὶ διαφέρει τούτῳ πολιτεία πολιτείας ἀγαθὴ φαύλης. […] ἐκ τῶν ὁμοίων ἐνεργειῶν αἱ ἕξεις γίνονται.

English Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Irwin (1999) and Crisp (2004).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako on Santorini, Cyclades, Greece.

*reads post, then proceeds to argue with everyone*

About the Text: This passage comes at the very end of his very long and very detailed treatise on argumentation.

Topics 164b8-15:

“You must not engage in argument with everyone, nor practice on anyone you happen to come across, for unfortunately against some people arguments necessarily degenerate. For against the person who does anything to escape from seeming beaten, it is just to try out anything to reach your conclusion, but it is not good form. Thus, it is necessary to not engage heedlessly with anyone you happen to come across, for unfortunately bad-reasoning necessarily follows. For, also, the ones who are practicing are unable to keep away from arguing contentiously.”

Οὐχ ἅπαντι δὲ διαλεκτέον, οὐδὲ πρὸς τὸν τυχόντα γυμναστέον. ἀνάγκη γὰρ πρὸς ἐνίους φαύλους γίνεσθαι τοὺς λόγους. πρὸς γὰρ τὸν παντως πειρώμενον φαίνεσθαι διαφεύγειν δίκαιον μὲν πάντως πειρᾶσθαι συλλογίσασθαι, οὐκ εὔσχημον δέ. διόπερ οὐ δεῖ συνεστάναι εὐχερῶς πρὸς τοὺς τυχόντας ‧ ἀνάγκη γὰρ πονηρολογίαν συμβαίνειν ‧ καὶ γὰρ οἱ γυμναξόμενοι ἀδυνατοῦσιν ἀπέχεσθαι τοῦ διαλέγεσθαι μὴ ἀγωνιστικῶς.

English Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Pickard-Cambridge (1984 in Barnes’ Complete Works) and Forster (1960).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako in Athens, Greece.

Thus, doggo << perfected human being. And thus, I present you a reductio ad absurdum.

Politics A.1 1252a32-38 (Barnes I.2):

“For human beings, when perfected, are the best of the animals, but, when separated from law and justice, they are the worst of all. For armed injustice is most dangerous. Humans are born with weapons for the sake of wisdom and virtue, which one may use for the worst ends. Thus, when devoid of virtue, human beings are the most unholy and most savage of animals, the most full of lust and gluttony. But justice is the bond of human communities.”

ὥσπερ γὰρ καὶ τελεωθὲν βέλτιστον τῶν ζῴων ὁ ἄνθρωπός ἐστιν, οὔτω καὶ χωρισθεὶς νόμου καὶ δίκης χείριστον πάντων. χαλεπωτάτη γὰρ ἀδικία ἔχουσα ὄπλα ‧ ὁ δὲ ἄνθρωπος ὅπλα ἔχων φύεται φρονήσει καὶ ἀρετῇ, οἷς ἐπὶ τἀναντία ἔστι χρῆσθαι μάλιστα. διὸ ἀνοσιώτατον καὶ ἀγριώτατον ἄνευ ἀρετῆς, καὶ πρὸς ἀφροδίσια καὶ ἐδωδὴν χείριστον. ἡ δὲ δικαιοσύνη πολιτικόν

English Translation by @masako.toyoda with reference to Jowett (1885), Rackham (1932), and Barnes (2016).

Background photo shot by @happinesium.masako on Naxos Island, Greece. August 2019.

Aristotle says I want YOU to be angered… by the right things, towards the right people, in the right way, at the right time, and for the right length of time.

Nicomachean Ethics, Δ 11 (OCT IV.5) 1125b31-6a6:

“Thus, the one who gets angry at the right things and towards the right people, also in the right way, at the right time, and for the right length of time is praised. This would be the even-tempered person, if indeed their even temper is praised. For the even-tempered person is undisturbed and not to be driven by their feelings, but is angered only when reason commands, thus in the right way and for the right length of time. And they seem to err more towards deficiency because the even-tempered person is inclined not to punish but more to forgive.

The deficiency, whether it is some lack of gall or whatever, is

objected to, because people who are not angered by the right things are foolish, as are those who are angered in the wrong way, at the wrong time, and towards the wrong people.”