This post is a roughly transcribed version of my understanding of Hugo Mercier & Helena Miton’s paper, “Utilizing simple cues to informational dependency”, in Evolution and Human Behavior (2019). Like all my posts, this is intended just for me, but if it is helpful for anyone else, that would of course make me happy 🙂

Utilizing simple cues to informational dependency

Hugo Mercier (CNRS, Paris) & Helena Miton (CEU, Budapest)

In this paper, Mercier & Miton investigate agents’ abilities to take informational dependence into account and further posit that whether or not cues are presented in an evolutionarily vs. non-evolutionarily valid way predict a cue’s salience.

[Note to Self:] Perhaps my skepticism towards this paper’s findings is due to my personal bias against pop evo psych (it is unrigorous, over-generalizing, and is presented almost always as though something being natural is some sort of justification for shit behavior–which I think is manifestly wrong), but the experiments in this paper really seem as though it was designed basically in order to produce confirmations of their hypotheses of which they were already convinced.

Motivation for the paper:

The number of people holding any given opinion X serves as a good cue regarding the validity of X. Mathematically this is pretty solidly proven (Condorcet 1785, Ladha 1992, Hastie & Kameda 2005, etc.).

Obviously, the reliability involved in following majority opinions depends on informational dependence of the individuals in the majority, i.e. whether or not individuals arrived at their opinions independently of each other.

But, lol! studies have conflicting results on people’s ability to gauge informational dependence.

- majority rules are prevalent also in animal kingdom, e.g. baboons

- humans even more so than other primates rely on cooperation and on communication

- Thus, humans should be able to take majority rules into account

- But, lol! studies have conflicting results on this

- they don’t: Mutz 1998, Mercier, Dockendorff & Schwartzberg, submitted

- they do: Bond 2005; Morgan, Rendell, Ehn, Hoppitt, and Laland 2012; Mercier & Morin submitted

They think an evolutionary framework can help us understand why certain cues are ignored and certain cues are followed. Basically, when majority rules are presented in an explicit, abstract manner, people don’t get it. But being told by many individuals personally is evolutionarily valid, and people follow that stuff. They think this distinction is basically like the difference between decisions from experience and decisions from descriptions.

Participants did not take informational dependencies into account for cues that are recent cultural inventions, e.g. correlation coefficients (Maines, 1990). Bunch of other studies showed evolutionarily valid cues being taken into account, e.g. Hu et al. 2015, Aikhenvald 2004.

[SUPER INTERESTING SIDE NOTE:] “In some languages, providing information about the sources of one’s opinions is made grammatically mandatory by evidentials. Even if evidentials do not make it mandatory to specify the exact source of one’s opinion they give the audience some relevant information. For example, speakers of Wanka Quechua must add a marker to their assertions specifying whether the information was acquired via direct perception, inference (i.e. one’s personal thought process), or hearsay (Aikhenvald, 2004, p. 43).”

Content of the paper:

This paper is concerned with testing when people are sensitive to informational dependence and when they are not. M&M test 5 hypotheses:

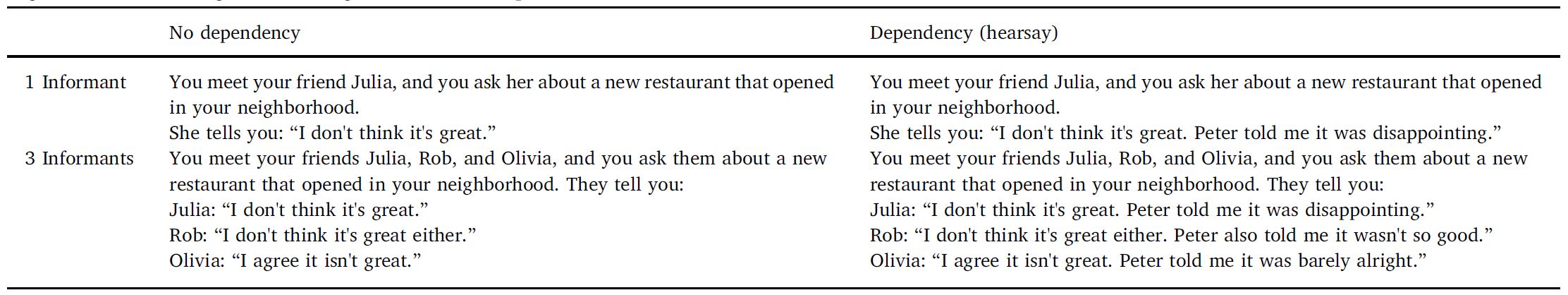

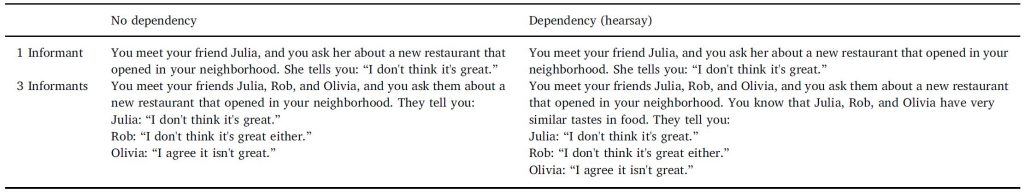

(H1) People take informational dependencies into account when they know several individuals owe their beliefs to the same source through hearsay (i.e. they have all heard the information from the same individual).

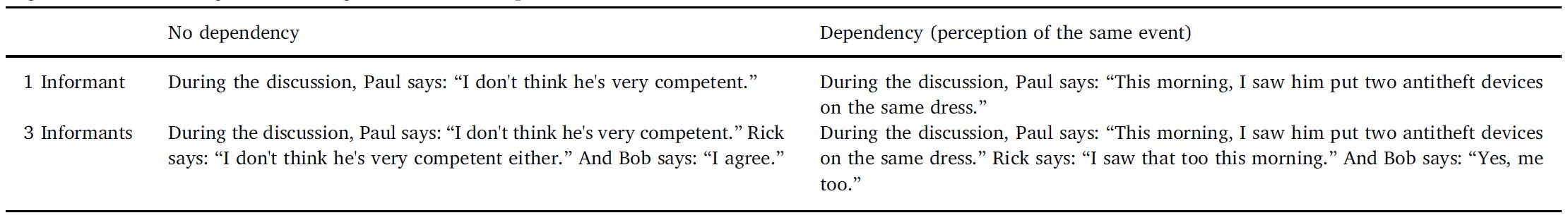

(H2) People take informational dependencies into account when they know several individuals owe their beliefs to perceiving the same event (e.g. they have all seen the same event).

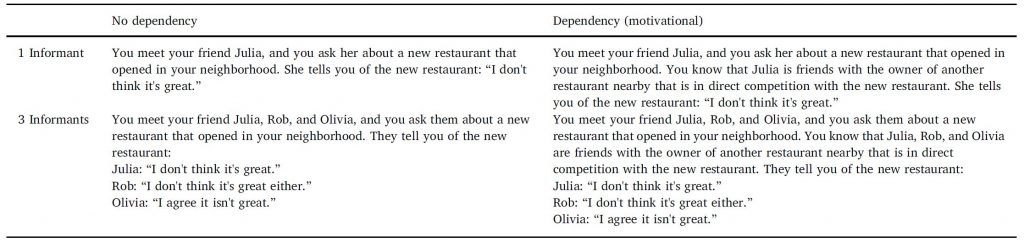

(H3) People take informational dependencies into account when they stem from common motivational biases (motivational dependencies).

(H4) People do not take informational dependencies into account when they stem from similarities in the cognitive makeup of individuals (cognitive dependencies).

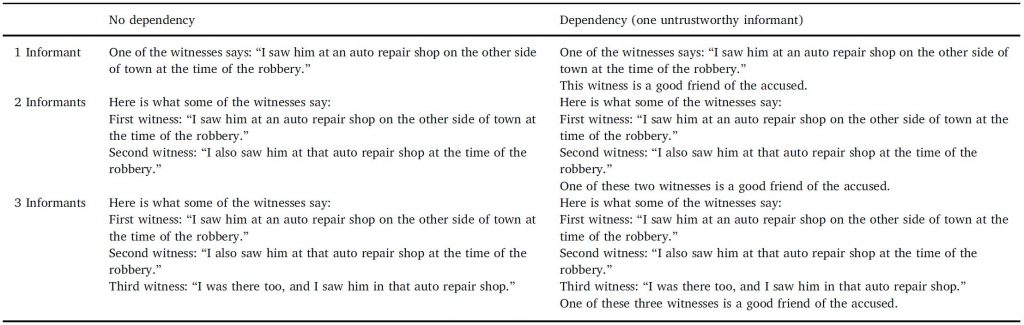

(H5) People discount majority opinions when a few members of the majority are suspected of not being trustworthy, compared to a situation in which no such suspicion arises.

M&M take their experiments to confirm all five of their hypotheses. They say that Experiment 1 confirms H1, Experiment 2 confirms H2, Experiment 3 confirms H3, Experiment 4 confirms H4, and Experiment 5 confirms H5.

M&M think their paper is cool because:

- “it confirms, using more ecologically valid stimuli, that participants are able to take simple cues to informational dependency into account.”

- “it offers, to the best of our knowledge, the first experiments bearing directly on whether participants can take internal dependencies (cognitive or motivational) into account.”

- “it offers, again to the best of our knowledge, the first experiments on the interaction between informational conformity and informant trustworthiness.”

They think that the evolutionarily vs. non-evolutionarily valid cues distinction should be studied further.

Experiments:

Manipulation of these variables in the vignettes presented to participants:

- # of informants {1, 3}

- dependency between the opinion of the informants

- framing {positive, negative}

One (n=398, replication n=394)

Analysis yielded:

- significant main effect of # of Informants

- no significant main effect of Dependency

- significant main effect of Framing

- significant critical interaction between Dependency and # of Informants

Two (n=399, replication n=400)

Analysis yielded:

- significant main effect of # of Informants

- no significant main effect of Dependency

- significant main effect of Framing

- significant critical interaction between Dependency and # of Informants

Three (n=395, replication n=397)

Analysis yielded:

- significant main effect of # of Informants

- significant main effect of Dependency

- significant main effect of Framing

- significant critical interaction between Dependency and # of Informants

Four (n=403, replication n=398)

Analysis yielded:

- significant main effect of # of Informants

- no significant main effect of Dependency

- significant main effect of Framing

- no significant interaction between Dependency and # of Informants

Five (n=888, replication n=988)

Analysis yielded:

- significant main effect of # of Informants

- significant main effect of Dependency

- significant main effect of Framing

- significant interaction between Dependency and # of Informants