This post is a roughly transcribed version of my hand-written notes on Harry Frankfurt’s essay “On Bullshit” and some thoughts. Like all my posts, this is intended just for me, but if it is helpful for anyone else, that would make me happy 🙂

Here is a recording of me reading the paper:

On Bullshit (1986)

by Harry Frankfurt

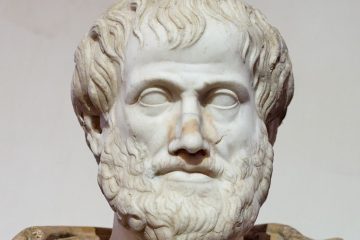

Harry Frankfurt (1929–, age 90), American philosopher (moral philosophy, phil of mind, phil of action, 17th century rationalism). Johns Hopkins, B.A. Ph.D.

Teaching:

- Ohio State (’56-’62)

- SUNY Binghamton (’62-’63)

- Rockefeller (’63-’76)

- Yale (’78-’87)

- Princeton (’90-’02), currently emeritus 🙂

Most Known For:

- freedom of the will

- higher-order volitions

- Frankfurt cases / Frankfurt counterexamples

- theory on bullshit

- Humean compatibilism

Major Works: “On Bullshit” (1986), Demons, Dreamers, and Madmen: The Defense of Reason in Descartes’ Meditations (1970), The Importance of What We Care About (1988), “Alternate Possibilities and Moral Responsibility” (1969),

In “On Bullshit”, Harry Frankfurt attempts to articulate the structure of in what bullshit consists. Identifying a lack of theory behind the concept, he offers how bullshit differs from other speech behaviors with similar characteristics (e.g. humbug, lying). In this post, I note the claims I found interesting, together with external facts and some of my thoughts.

Frankfurt begins by taking Max Black’s proposed definition for ‘humbug’ and tries to understand its meaning and how it differs from bullshit. The proposed definition is the following:

“deceptive misrepresentation, short of lying, especially by pretentious word or deed, of somebody’s own thoughts, feelings or attitudes.”

Frankfurt takes each component of this definition as:

1) deceptive misrepresentation, i.e. a deliberate speech act, with an intention to deceive. This entails that the state of mind is similar to that of lying: agent X believes P but conveys ~P, with the truth value of P being irrelevant.

2) short of lying, Frankfurt thinks Black is suggesting that there is a continuum of speech acts on which there is a segment for lies, and humbug is some segment prior to that segment.

– My immediate reaction is that this is not necessarily suggested, though I haven’t read Black’s work. One could very easily conceptualize these speech acts as mapped onto a plane where each concept has a certain locus and somehow the sort of speech act that humbug is is outside of the circle of what constitutes lying. I do not intend to imply that these would be clean circles. Even more of a side note: My personal view on how conceptual space would be mapped out is probably more like neuron clusters in the brain that connect and overlap in various ways.

3) especially by pretentious word or deed, [note to self: uninteresting, included for completeness], “when bullshit is pretentious, this happens because pretentiousness is its motive rather than a constitutive element of its essence”.

4) misrepresentation… of somebody’s own thoughts, feelings, or attitudes, what is being misrepresented? both 1) the agent’s own state of mind, and 2) the state of affairs.

– [note to self:] I want to explore this distinction more—the responsibility that comes along with misrepresenting one’s state of mind (e.g. “[to pretend] to have a desire or feeling [one] does not actually have”, potential options of plans) versus misrepresenting the state of affairs (e.g. facts of the matter). The latter seems, at first glance, to more heavily spill over and affect epistemic responsibility, though both certainly affect the epistemic virtue of a situtation and some cases come to mind that seem more damaged by the former. I just don’t know if either of the two makes a speech act more inherently morally wrong than the other.

From Black’s understanding of humbug, Frankfurt gleans two things which, he says, ought for bullshit be considered differently than how Black spells these features out. 1) bullshit is short of lying and that 2) those who perpetrate bullshit misrepresent themselves in a certain way… in what way?

For the remainder of the paper, Frankfurt explores the structures of the following two points:

- bullshit differs from lying

- how those who perpetrate bullshit misrepresent themselves

Q: How do bullshit and lying compare?

Both are “trying to get away with something”

Case I: Wittgenstein & Fania Pascal (1930s)

Bullshitters are “not even concerned whether [their] statements are correct” and have an “indifference to how things really are”.

“Pascal offers a description of a certain state of affairs without genuinely submitting to the constraints which the endeavor to provide an accurate representation of reality imposes. Her fault is not that she fails to get things right, but that she is not even trying.” “She is not concerned with the truth-value of what she says. That is why she cannot be regarded as lying; for she does not presume that she knows the truth, and therefore she cannot be deliberately promulgating a proposition that she presumes to be false.

Case II: Oxford English Dictionary, bull sessions

Bullshit in bull sessions is “disconnected from the legitimating motives of the activity upon which [it] intrude[s]… disconnected from a concern with the truth“.

In bull sessions, “provision is made for enjoying a certain irresponsibility” and its participants rely “upon a general recognition that what he expresses or says is not to be understood as being what he means wholeheartedly or believes unequivocally to be true. The purpose of the conversation is not to communicate beliefs”.

Case III: Oxford English Dictionary, example, Ezra Pound’s Canto LXXIV:

Hey Snag wots in the bibl’?

Wot are the books ov the bible?

Name ’em, don’t bullshit ME.

The character is calling the bluff. “Lying and bluffing are both modes of misrepresentation or deception… Unlike plain lying, however, it is more especially a matter not of falsity but of fakery… the essence of bullshit is not that it is false, but that it is phony…. although [bullshit] is produced without concern with the truth, it need not be false. The bullshitter is faking things. But this does not mean that he necessarily gets them wrong.”

Case IV: Dirty Story by Eric Ambler

Arthur Abdel Simpson’s father’s advice: “Never tell a lie when you can bullshit your way through.”

“We may seek to distance ourselves from bullshit, but we are more likely to turn away from it with an impatient or irritated shrug than with the sense of violation or outrage that lies often inspire.”

Lying has objective constraints imposed by what an agent takes to be true versus bullshit does not have the same constraints. There is more freedom involved in bulshitting.

– It seems to me one of Harry Frankfurt’s overall points of the essay is to make clear how dangerous and problematic bullshit is and thus, I infer, that we ought to change this characteristic difference between lying and bullshitting.

Bullshit “essentially misrepresents… neither the state of affairs to which it refers nor the beliefs of the speaker concerning that state of affairs”. The bullshitter “may not deceive us, or even intend to do so, either about the facts or about what he takes the facts to be. What he does necessarily attempt to deceive us about it his enterprise… in a certain way he misrepresents what he is up to.” The bullshitter hides “that the truth-values of his statements are of no central interest to him”.

On the other hand, “it is impossible for someone to lie unless he thinks he knows the truth. Producing bullshit requires no such conviction… His eye is not on the facts at all, as the eyes of the honest man and of the liar are, except insofar as they may be pertinent to his interest in getting away with what he says. He does not care whether the things he says describe reality correctly. He just picks them out, or makes them up, to suit his purpose.”

In the last few pages of the paper, Frankfurt explicitly addresses why bullshit is so–I’d describe what he conveys as–dangerous, though this was alluded to earlier in the paper, and why there is so much of it.

He addresses St. Augustine’s eight-fold distinction on the types of lies and in so doing picks out what Augustine says are, strictly speaking, lies:

There is a distinction between a person who tells a lie and a liar. The former is one who tells a lie unwillingly, while the liar loves to lie and passes his time in the joy of lying. … The latter takes delight in lying, rejoicing in the falsehood itself.

I realize that the following is not precise enough and would depend on many other assumptions, but a lie, in the strict sense, would become an occurrence like: an agent A communicates (with whatever means) a claim X that A believes to be false, for the purpose of making another agent B take X to be true and by which A gains feelings or pleasure. This is interesting to me because it is similar in flavor to Aristotle’s distinction between someone who does vicious things and a vicious person; the vicious person has feelings of pleasure in doing a vicious action.

I wonder about the applications of this sort of a strict definition. Let us suppose we accept this strict definition, only when a lie is told in this way do we accuse others of lying. Well, we would have, as Frankfurt notes, significantly fewer instances of what we call a lie and fewer people to call a liar; they would be “rare and extraordinary”. I wonder if this would lead to higher levels of trust among community members. Would it allow for more empathetic responses from others when lies are told for the sake of other purposes? Would accepting a conception like this be instead used to excuse more terrible behaviors? [Note to self: Think about this.]

Frankfurt uses Augustine’s distinction to discuss how “for most people, the fact that a statement is false constitutes in itself a reason, however weak and easily overridden, not to make the statement.” yet “for the bullshitter, it is in itself neither a reason in favor nor a reason against” uttering what they utter. A bullshitter “pays no attention to it at all”. And this is the reason why bullshit is dangerous. Accepting bullshit and having an attitude to bullshit, etc. erode at truth even more than lying does.

When one takes an attitude such as this, Frankfurt claims, there are two paths. Either you stop making any assertions by desisting from telling truths or from deceiving… which he thinks is not a real option, or you continue making assertions that are bullshit. The latter is basically all we’ve got.

This is related to why there is an abundance of bullshit, Frankfurt claims, in the world. Bullshit is a course of option that is unavoidable when there are demands for agents to make seemingly-coherent assertions even when they are ignorant of the topic at hand.

The historical context within which Frankfurt wrote this essay could be important to have in mind in understanding his next claim. The 1980’s saw a spiked increase in the masses’ interest in international affairs. While the CNN effect is generally understood as a 90’s phenomenon, it already played a role in international affairs, which is exemplified in international responses to many of 1989’s events, e.g. the Tiananmen Square Incident, the fall of the Berlin Wall, etc. The age in which Frankfurt wrote this essay is exactly the age in which the ordinary person began to have, through watching video, strong emotional responses, and thus to hold–I think it’s fair to assume–strong opinions, on many issues of which they are not adequately informed about to (epistemically) responsibly form opinions. This is, of course, a thought with a view to very high standards for epistemic responsibility and is not to say that many from earlier times did not have strong opinions on affairs that they did not directly see in day to day life. For example, proponents of abolishing slavery in the early 1800’s did not have 24-hour color TV…. but to this, the idea still holds, given the larger circulation of ‘activist’ books against slavery, e.g. Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Anyway, in this backdrop, Frankfurt claims: “The lack of any significant connection between a person’s opinions and his apprehension of reality will be even more severe, needless to say, for someone who believes it his responsibility, as a conscientious moral agent, to evaluate events and conditions in all parts of the world.”

He also attributes the proliferation of bullshit to other fundamental sources. Interestingly, and I think extremely insightfully, he identifies the forms of skepticism that “deny that we can have any reliable access to an objective reality and which therefore reject the possibility of knowing how things truly are.” These anti-realist positions undermine the efforts people put in to determine what is true and false. The dangerous alternative, Frankfurt identifies, is the pursuit of sincerity instead of truth, wherein “the individual turns toward trying to provide honest representations of himself…” and “devotes himself to being true to his own nature.”

I absolutely adore his next and final sentences:

It is preposterous to imagine that we ourselves are determinate, and hence susceptible both to correct and to incorrect descriptions, while [also] supposing that the ascription of determinacy to anything else has been exposed as a mistake… Facts about ourselves are not peculiarly solid and resistant to skeptical dissolution. Our natures are, indeed, elusively insubstantial–notoriously less stable and less inherent than the natures of other things. And insofar as this is the case, sincerity itself is bullshit.

Facts I ought to remember / words I did not know:

‘humbug’ Synonyms, hahaha: balderdash, claptrap, hokum, drivel, buncombe

a bull session: “participants try out various thoughts and attitudes in order to see how it feels to hear themselves saying such things and in order to discover how others respond, without it being assumed that they are committed to what they say: It is understood by everyone in a bull session that the statements people make do not necessarily reveal what they really believe or how they really feel. The main point is to make possible a high level of candor and an experimental or adventuresome approach to the subjects under discussion. Therefore provision is made for enjoying a certain irresponsibility, so that people will be encouraged to convey what is on their minds without too much anxiety that they will be held to it. Each of the contributors to a bull session relies, in other words, upon a general recognition that what he expresses or says is not to be understood as being what the means wholeheartedly or believes unequivocally to be true.” Basically, Port & Policy at Oxford.

Further work for me to do:

- Understand the Principle of Alternate Possibilities and the core argument for incompatibilism [incompatibility of responsibility and causal determinism] (Robert Kane)

- Understand the rejection of premise 2 of the core argument by A.J. Ayers, D. Dennett… and its shortcomings

- Read Harry Frankfurt’s rejection of the Principle of Alternate Possibilities, i.e. an agent is responsible for X if they could have done otherwise–Frankfurt cases demonstrate that responsibility does not require the freedom to do otherwise: “Alternate Possibilities and Moral Responsibility” (1969)

- Read on the two-horned rejection of the Frankfurt cases

- Read works on the various accounts of lying.

- On Lying, Saint Augustine

- Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals, Kant

- “On a Supposed Right to Lie from Philanthropic Concerns”, Kant

- The Metaphysics of Morals, Kant

- the Mahābhārata

- Isenberg 1973

- Primoratz 1984

- etc.

- Maybe read Dirty Story by Eric Ambler.

Bibliography:

Frankfurt, Harry G. On Bullshit. Princeton University Press, 2005.