This post is a roughly transcribed version of my hand-written notes on Hannah Arendt’s essay, “The Freedom to be Free”. Like all my posts, this is intended just for me, but if it is helpful for anyone else, that would make me happy 🙂

The Freedom to be Free (1953)

by Hannah Arendt

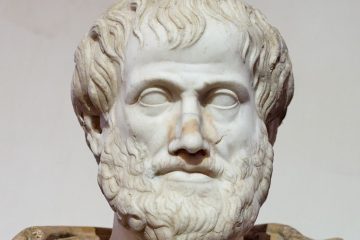

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975, 69, heart attack), German-American philosopher/political theorist. Studied under and had an affair with Martin Heidegger at the University of Marburg. Completed her Ph.D. (1929) in philosophy under Karl Jaspers at the University of Heidelberg. Jewish, thus experienced antisemitism in the 1930’s and became imprisoned. Released, she fled to Paris (1933) and helped Jewish youth emigrate to Palestine. She was detained by the French when the Germans arrived (1940); she fled again (1941) this time to New York and became a US citizen (1950). She taught at many schools (including Notre Dame, Berkeley, Princeton!, Chicago, the New School) while avoiding tenure-track jobs. Married twice. Most famous for: “the banality of evil” in her thoughts on Eichmann’s trial, how easy it is for normal people can do terribly evil things, etc. Major works: The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), The Human Condition (1958), Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), On Revolution (1963), unfinished: The Life of the Mind.

This essay argues for the importance of understanding the cause of revolution, the potential benefits and consequences of having or not having this understanding. In brief, it analyzes the American and French revolutions and tries to understand the conditions within which they were successful or a failure, respectively.

Arendt does this in a style of writing I dislike which lacks a clear argumentative structure and relies heavily on quotations of other thinkers to further her points.

Despite this stylistic disagreement, I found her claims insightful and impressively predictive of the past nearly 70 years of political history. I note the claims I found interesting, below, together with facts and thoughts I think are relevant to understand her claims:

In 1953, Arendt had spent 17 years fleeing without citizenship until acquiring US citizenship in 1950. I imagine that the freedom of expression she felt in New York City contrasted greatly from her Jewish experience under anti-semitic influences in Germany and France from which she fled.

Arendt suggests that the future maintenance of the United States as a great power in international affairs will depend on its ability to understand the nature of revolutions, how they come about, and what is at stake to change through them. This understanding is necessary for it to successfully wield its power.

She thinks that the foreign policy of the United States in the 1950’s (e.g. Bay of Pigs, the wars) demonstrates a lack of understanding of the circumstances upon which the nation was founded and the circumstances upon which it succeeded to form the successful republic into which it has grown. This seems fair.

“No revolution is even possible where the authority of the body politic is intact… where the armed forces can be trusted to obey the civil authorities. Revolutions are not necessary but possible answers to the devolution of a regime, not the cause but the consequence of the downfall of political authority. Wherever these disintegrative processes have been allowed to develop unchecked, usually over a prolonged period, revolutions may occur under the condition that a sufficient number of the populace exists which is prepared for a regime’s collapse and is willing to assume power. Revolutions always appear to succeed with amazing ease in their initial stages, and the reason is that those who supposedly “make” revolutions do not “seize power” but rather pick it up where it lies in the streets.”

[This text reminded me of a reading in a course by Professor Rory Truex (Princeton University) during my undergrad. It built upon Kuran’s work in the 1980’s/90’s to discuss the mechanism by which large-scale protests necessary for the masses to overthrow the current state of affairs come about.

The reading discussed a waterfall effect that can occur when there is a large proportion of the population with a similar set of grievances. When a small percentage of people who will in any case mobilize reach a sufficiently high threshold, a slightly larger percentage of people mobilize.

Through the repetition of this pattern: reach the threshold, trigger those who would not otherwise protest, reach a higher threshold of the number of protesters, trigger more… the masses can manage to create a significant enough protest to potentially cause a societal change. Note to self: reread article.]

Basically, Arendt thinks that the American and French Revolutions provide the framework upon which to understand the successes or failures of all subsequent revolutions in the 19th and 20th centuries all around the world.

To note, the American and French 18th century revolutions dramatically changed the meaning of ‘revolution’ to a restoration of the inalienable rights to decide public affairs and of ‘freedom’ itself.

Let us turn to her analysis of the American and French Revolutions. Arendt overstates, or at least presents an unconvincing case for, the ‘role of antiquity’ in post-18th century revolutionary history. Perhaps this assessment stems from my relevant ignorance of the thoughts prevalent before the American and French revolutions.

She attributes the demand for freedom in the form of participation in public affairs to the Renaissance man’s affinity to antiquity. It is true that the societal elite led the revolutions in both the 13 colonies and France.

Certainly, Arendt is right in that there was an expansion, post-Renaissance, of the stratum of wealthy men who held positions that allowed for considerable leisure to think their thoughts important enough, and thus to feel in a way entitled, to demand their own freedom. It seems right to think this an important factor that contributed to the revolutions occurring when they did.

However, her dismissal “Needless to add, where men live in truly miserable conditions this passion for freedom is unknown.” to explain the absence of revolutions prior to the 18th century or post-18th century seems unfounded. I also think it undercuts her analysis of what happened in the French Revolution.

This understanding of human nature in the face of poverty is in tension with post-18th century international revolutions and with her praise for John Adams’ claim that every person no matter their background has a strong desire to be seen and heard by others, i.e. play a role in society.

She attributes the failure of the French Revolution in large part to that the participants of the French Revolution were not yet free (as compared to the US colonists) to be free because of their relative poverty:

“to be free for freedom meant first of all to be free not only from fear but also from want.”

Freedom from fear and freedom from want is both necessary for freedom in the new sense of the term, this freedom to be free. The French, Arendt claims, were unsuccessful in filling the power vacuum created by their revolution, because the masses were not in a mindset ready for a republic.

The failure, Arendt thinks, of most of the subsequent revolutions in human history lies primarily in that most of the world share the factor of fundamental poverty–and thus lack the freedom from want, a necessary condition for possessing freedom. In the US on the other hand, the truly miserable (i.e. the slaves) were fully overlooked.

Arendt’s claim seems overgeneralized and also inaccurate. The primary trigger for many revolutions, e.g. Russian or even French, can–I think–be attributed to the overwhelming poverty of the masses. Their subsequent failures can be equally attributed to their planners’ lack of foresight for what would happen afterwards.

Despite my difference in opinion regarding the exact causes for exact effects in the historical examples, her general conclusion regarding poverty’s influence on revolutions may still hold true:

“A comparison of the two first revolutions, whose beginnings were so similar and whose ends so tremendously different, demonstrates clearly, I think, not only that the conquest of poverty is a prerequisite for the foundation of freedom, but also that liberation from poverty cannot be dealt with in the same way as liberation from political oppression. For if violence pitted against violence leads to war, foreign or civil, violence pitted against social conditions has always led to terror. Terror rather than mere violence, terror let loose after the old regime has been dissolved and the new regime installed, is what either sends revolutions to their doom, or deforms them so decisively that they lapse into tyranny and despotism.”

This conclusion, combined with our modern understanding of relative poverty, seems to me extremely insightful and helpful to pin alongside our understanding of contemporary political movements. How ought we approach the socioeconomic / political conflicts we have today in light of this?

Another conclusion Arendt makes in her essay also struck me as particularly insightful. Her words are rhetorically more powerful than any summary I can offer:

“The collapse of authority and power, which as a rule comes with surprising suddenness not only to the readers of newspapers but also to all secret services and their experts who watch such things, becomes a revolution in the full sense of the word only when there are people willing and capable of picking up the power, of moving into and penetrating, so to speak, the power vacuum…. What then happens… depends most of all upon subjective qualities and the moral-political success or failure of those who are willing to assume responsibility.”

In conclusion, Arendt presses the importance of the leaders of the United States to understand the nature of revolution, i.e. not-only-political-but-also-societal overthrow, so that it may be better able to guard against the deterioration of the nation’s international influence. Given the great and insightful way in which the Founding Fathers built the United States and the values upon which they founded it, it is paramount for the nation to recognize the importance of and devote more consideration into its decisions. Only then can the United States fully realize its proper contribution to the world.

Facts I ought to remember / words I didn't know:

coeval (adj./n.) – contemporary

apropos (prep./adj.) – with reference to, concerning / very appropriate to a particular situation. phrase: “apropos of nothing”. [Etymology: French, mid 17th century]

Korean War: Jun 25th, 1950 – Jul 27th, 1953

Algerian War (Algerian Revolution): Nov 1st, 1954 – Mar 19th, 1962

Vietnam War (Second Indochina War / Resistance War Against America): Nov 1st, 1955 – April 30th, 1975

Fact: novus ordo seclorum, i.e. new order of the ages – the second of two mottos that appear on the back side of the Great Seal of the United States, created 1782

Further work for me to do:

- Find & Reread old Chinese Politics readings

- Read Common Sense by Thomas Paine

- Close read the Declaration of Independence

- Read Eichmann in Jerusalem

- Reread / Finish The Human Condition